“Drums, eh,” says Keith Richards in answer to a fan question on the subject. “Without it you’re kinda nowhere.” He’s got a point. An ace drummer can be the spine, muscle, and even soul of a great band. Pounding, swinging, and smashing away behind showy guitarists and flamboyant frontmen, drummers sometimes have problems being seen, but never heard. But while John Bonham or Keith Moon never got lost in the mix, it’s a rare thing to hear them out of it. The proliferation of rock band video games and isolated tracks posted to Youtube allow us to listen to the nuances of drum grooves we may feel we know by heart, such as Bonham’s driving beat behind Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love.”

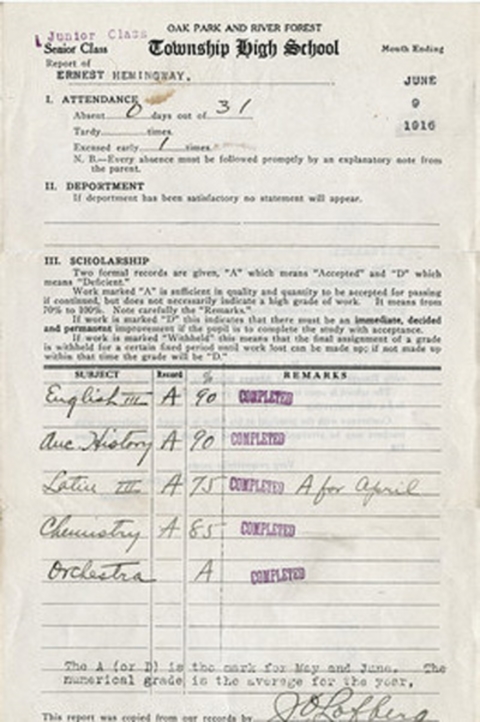

In a previous post, we brought you a rough mix of the song and Jimmy Page describing its creation. Page wanted Bonham’s drum track to “really stand out, so that every stick stroke sounded clear and you could really feel them.” It certainly does that. The drum track above is all about feeling. As a result of the recording techniques of the time, writes producer/engineer Bobby Owinski, drum tracks tended to sound “like a single instrument,” since they were recorded with only two or three mics capturing the space around the kit, rather than the sound of individual pieces. “Still,” Owinski writes of this track, “there’s plenty of power in [Bonham’s] kick and snare, because he played them hard!” In addition to his power, Bonham is known for his laid-back groove, due to his tendency for playing slightly behind the beat, a quality Youtube drum instructor Terry Keating of Bonzoleum ascribes to “temperament.”

Bonham’s style consisted mainly of creative uses of triplets, so much so that McSweeny’s had a good laugh about his constant use a similar pattern. One of my favorite drummers—crankiest man in rock Ginger Baker—also disparages Bonham’s playing, as well as that of another alcoholic drum star, Keith Moon. But Ginger Baker doesn’t tend to like anyone, and Moon’s playing, while maybe not virtuosic or especially disciplined, was, like his persona, insane. Drum Magazine describes Moon’s style as “tribal, primitive, and impulsive, with him often stomping the bass drums and pounding his wall of toms like a madman” (clearly Moon inspired the Muppets’ Animal). Moon’s many kits often consisted of double bass drums and double rows of toms, and he played them as hard as possible almost all the time. Hear him above thrashing with abandon through “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

Seemingly miles away from the madness of Keith Moon, Rush’s Neil Peart is a highly technical drummer with impeccable on-the-beat timing and a drum setup that has grown so extensive and complicated over the years that he almost disappears into its depths. Peart’s playing combines the power and stamina of Bonham with complex patterns whose rhythmic dynamics shift subtly several times throughout each song. Check out the isolated drum track for “Tom Sawyer” above as a classic example of Peart’s technique and you may see why he’s classed as one of the all-time best rock drummers (though I wouldn’t class him as one of rock’s greatest lyricists).

Although I’m an admirer of Neil Peart’s drumming, I can’t say I’m much of a Rush fan. Police drummer Stewart Copeland feels the same. In an interview with Music Radar, he jokes about “pull[ing] Neil’s chain at every possible opportunity” for the self-indulgent excess of drum solos (though Copeland gamely played one during David Letterman’s “Drum Solo Week” in 2011). Copeland talks about “a time when bands like Rush were the epitome of what The Police were theoretically against, which was an overemphasis on musicality.” Nonetheless, Copeland is one of the most musical of drummers, making use of odd time signatures and polyrhythmic syncopation to create a thoroughly unique and instantly recognizable style (which has even inspired neuroscience studies). The drum track above comes from “Next to You,” a song on the band’s debut album, during their decidedly anti-Rush phase. While the song itself is uptempo punk rock, Copeland’s Gene Krupa-like drumming, heard in isolation, presages the unusual quirks to come as the band stretched out into jazz and reggae territory.

The sheer number of bands Foo Fighters frontman and former Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl has drummed for is impressive, and a testament to his machine-like speed and timing. Drummer and Portlandia star Fred Armisen may be Grohl’s biggest fan. “Every drum part he does is a masterpiece,” says Armisen, “He’s never just heavy for heavy’s sake or rock for rock’s sake—it’s all so musical, with an incredible sense of dynamics. Every generation has their drumming guy, and Dave is ours.” Even Kurt Cobain, never one to overpraise, once called Grohl “the best drummer in the world.” Maybe a bit of hyperbole, but Grohl’s damned good, even at his most straightforward, as above in his pounding drumbeat for “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Grohl’s powerhouse playing isn’t the most versatile. He had some trouble adjusting to quieter environs, and Cobain nearly banned him from the band’s legendary “Unplugged” performance for his too-aggressive playing in rehearsals. Nonetheless, when it comes to punk, hardcore, and serious rock, Grohl’s the man.

I can’t resist ending with the isolated track of what maybe be my all-time favorite drum part, Ringo Starr’s wildly funky business at the end of “Strawberry Fields Forever.” Some of the drums here are overdubbed, with several different percussion parts blended with Starr’s full-kit freak out. Starr has taken a lot of completely undeserved flak for his supposed limitations as a drummer, but as Samuel Belkin writes at The Examiner, “his latter day drum patterns are […] often sophisticated, and always idiosyncratic […] nobody has ever been able to sound quite like Ringo.” Ultimately, in my book, what distinguishes a truly great drummer from thousands of technically proficient players is a quality no one can teach or emulate: Personality.

Related Content:

7 Female Bass Players Who Helped Shape Modern Music: Kim Gordon, Tina Weymouth, Kim Deal & More

Listen to The John Bonham Story, a Radio Show Hosted by Dave Grohl

Keith Moon’s Final Performance with The Who (1978)

Hear the Isolated Vocal Tracks for The Beatles’ Climactic 16-Minute Medley on Abbey Road

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.