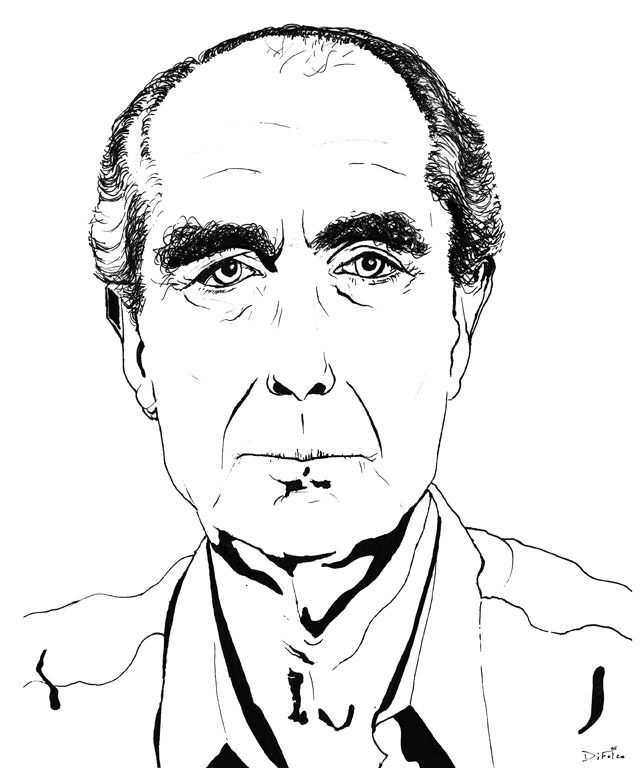

The poetry of Charles Bukowski deeply inspires many of its readers. Sometimes it just inspires them to lead the dissolute lifestyle they think they see glorified in it, but other times it leads them to create something compelling of their own. The quality and variety of the Bukowski-inspired animation now available on the internet, for instance, has certainly surprised me.

At the top of the post, we have Jonathan Hodgson’s adaptation of “The Man with the Beautiful Eyes,” which puts vivid, colorful imagery to Bukowski’s late poem that draws from his childhood memories of a mysterious, untamed young man in a run-down house whose very existence reminded him “that nobody wanted anybody to be strong and beautiful like that, that others would never allow it.” Below, you can watch Monika Umba’s even more unconventional animation of “Bluebird”:

Without any words spoken on the soundtrack and only the title seen onscreen — a challenging creative restriction for a poetry-based short — Umba depicts the narrator’s “bluebird in my heart that wants to get out.” But the narrator, “too tough for him,” beats back the bluebird’s escape with whiskey, cigarettes, and a policy of only letting him roam “at night sometimes, when everybody’s asleep.”

You’ll find Bradley Bell’s interpretation of “The Laughing Heart,” a poem that advises its readers not to let their lives “be clubbed into dank submission,” to “be on the watch,” for “there are ways out.” “You can’t beat death,” Bukowski writes, “but you can beat death in life, sometimes.” In Bell’s short, these words come from the mouth of the also famously dissolution-chronicling singer-songwriter Tom Waits, certainly Bukowski’s most suitable living reader (and one who, all told, comes second only to the man himself). Only fitting that one inspiring creator delivers the work of another — in the sort of labor of enthusiasm that, too, will inspire its audience to create.

At the bottom the post, you will find “Roll the Dice,” an animation suggested by one of our readers, Mark.

You can find readings of Bukowski poems in the poetry section of our collection of Free Audio Books.

Related Content:

The Last (Faxed) Poem of Charles Bukowski

Listen to Charles Bukowski Poems Being Read by Bukowski, Tom Waits and Bono

“Don’t Try”: Charles Bukowski’s Concise Philosophy of Art and Life

Charles Bukowski Sets His Amusing Conditions for Giving a Poetry Reading (1971)

Charles Bukowski: Depression and Three Days in Bed Can Restore Your Creative Juices (NSFW)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.