Image by The USO, via Flickr Commons

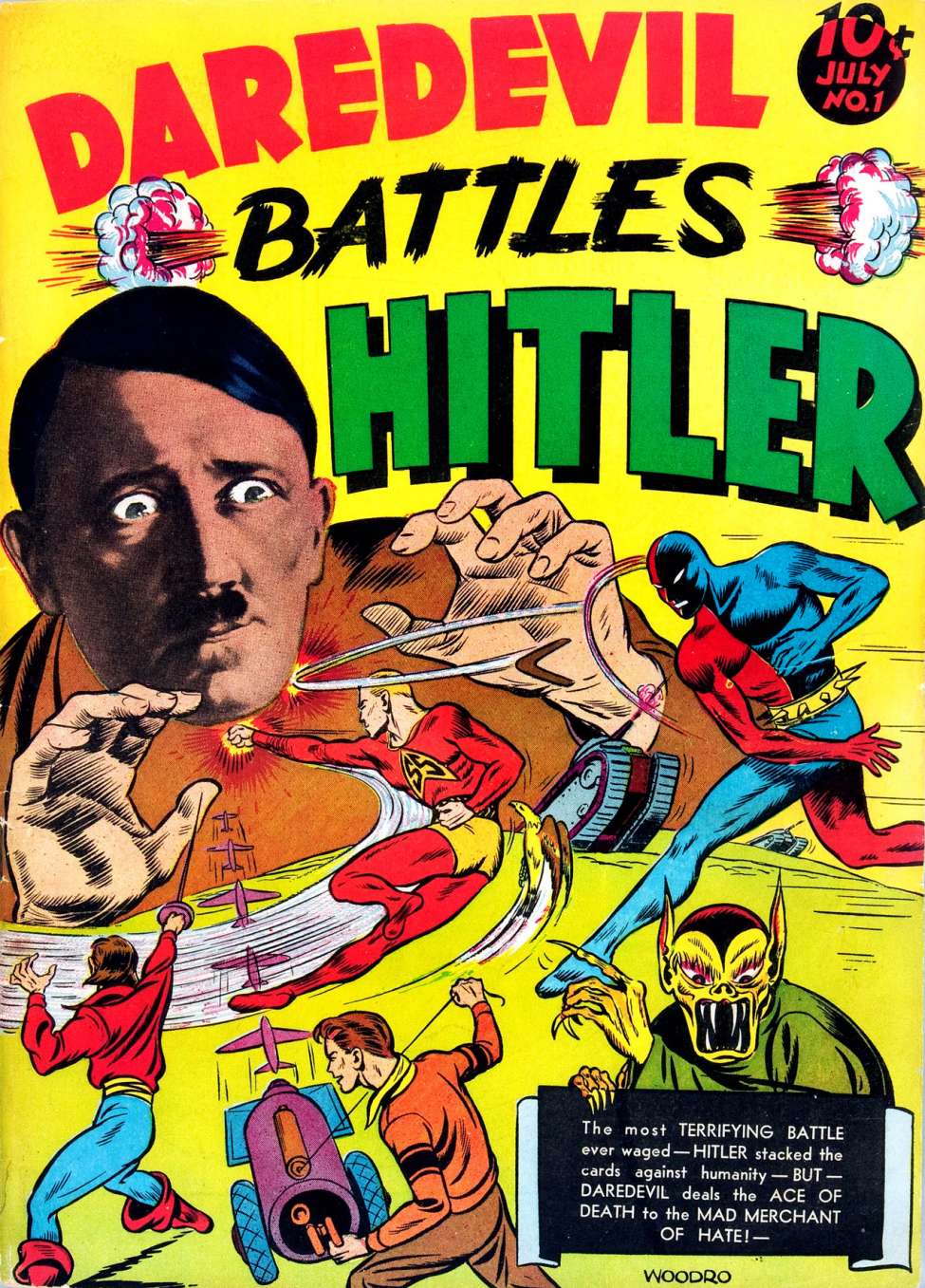

I first discovered Stephen King at age 11, indirectly through a babysitter who would plop me down in front of daytime soaps and disappear. Bored with One Life to Live, I read the stacks of mass-market paperbacks my absentee guardian left around—romances, mysteries, thrillers, and yes, horror. It all seemed of a piece. King’s novels sure looked like those other lurid, pulpy books, and at least his early works mostly fit a certain formula, making them perfectly adaptable to Hollywood films. Yet for many years now, as he’s ranged from horror to broader subjects, King’s cultural stock has risen far above his genre peers. He’s become a “serious” writer and even, with his 2000 book On Writing—part memoir, part “textbook”—something of a writer’s writer, moving from the supermarket rack to the pages of The Paris Review.

Few contemporary writers have challenged the somewhat arbitrary division between literary and so-called genre fiction so much as Stephen King, whose status provokes word wars like this recent debate at the Los Angeles Review of Books. Whatever adjectives critics throw at him, King plows ahead, turning out book after book, refining his craft, happily sharing his insights, and reading whatever he likes. As evidence of his disregard for academic canons, we have his reading list for writers, which he attached as an appendix to On Writing. Best-selling genre writers like Nelson DeMille, Thomas Harris, and needs-no-introduction J.K. Rowling sit comfortably next to lit-class staples like Dickens, Faulkner, and Conrad. King recommends contemporary realist writers like Richard Bausch, John Irving, and Annie Proulx alongside the occasional postmodernist or “difficult” writer like Don DeLillo or Cormac McCarthy. He includes several non-fiction books as well.

King prefaces the list with a disclaimer: “I’m not Oprah and this isn’t my book club. These are the ones that worked for me, that’s all.” Below, we’ve excerpted twenty good reads he recommends for budding writers. These are books, King writes, that directly inspired him: “In some way or other, I suspect each book in the list had an influence on the books I wrote.” To the writer, he says, “a good many of these might show you some new ways of doing your work.” And for the reader? “They’re apt to entertain you. They certainly entertained me.”

10. Richard Bausch, In the Night Season

12. Paul Bowles, The Sheltering Sky

13. T. Coraghessan Boyle, The Tortilla Curtain

17. Michael Chabon, Werewolves in Their Youth

28. Roddy Doyle, The Woman Who Walked into Doors

31. Alex Garland, The Beach

42. Peter Hoeg, Smilla’s Sense of Snow

49. Mary Karr, The Liar’s Club

53. Barbara Kingsolver, The Poisonwood Bible

54. Jon Krakauer, Into Thin Air

58. Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It and Other Stories

62. Frank McCourt, Angela’s Ashes

66. Ian McEwan, The Cement Garden

67. Larry McMurtry, Dead Man’s Walk

70. Joyce Carol Oates, Zombie

71. Tim O’Brien, In the Lake of the Woods

73. Michael Ondaatje, The English Patient

84. Richard Russo, Mohawk

86. Vikram Seth, A Suitable Boy

93. Anne Tyler, A Patchwork Planet

Like much of King’s own work, many of these books suggest a spectrum, not a chasm, between the literary and the commercial, and many of their writers have found success with screen adaptations and Barnes & Noble displays as well as widespread critical acclaim. For the full range of King’s selections, see the entire list of 96 books at Aerogramme Writers’ Studio.

via Galleycat

Related Content:

Stephen King Turns Short Story into a Free Webcomic

Stephen King Writes A Letter to His 16-Year-Old Self: “Stay Away from Recreational Drugs”

Stephen King Reads from His Upcoming Sequel to The Shining

Stanley Kubrick’s Annotated Copy of Stephen King’s The Shining

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness