For a sport obsessed with statistical averages, baseball seems to thrive like no other on outrageous anecdotes and singular characters. One of those characters, pitcher Dock Ellis, had a drug-fueled run in the 70s with the Pittsburgh Pirates, claiming that he almost never pitched a game sober, including several National League East Championships and a 1971 World Series win. The drugs eventually became too much and he got help, but they gave Ellis his career best anecdote, the story he tells in the short film above, “Dock Ellis and the LSD No-No.” It’s animated by James Blagdon from an interview Ellis gave to Donnell Alexander and Neille Ilel that aired on NPR in March of 2008.

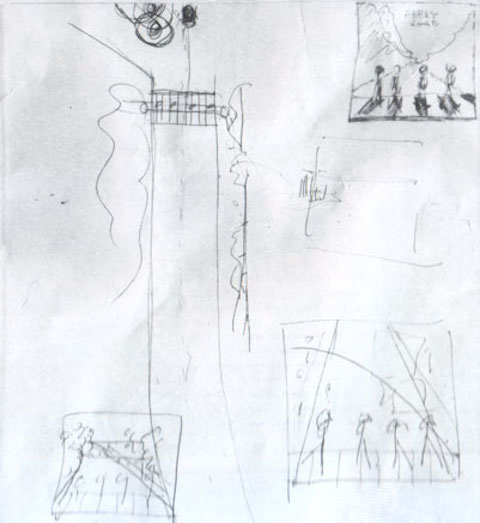

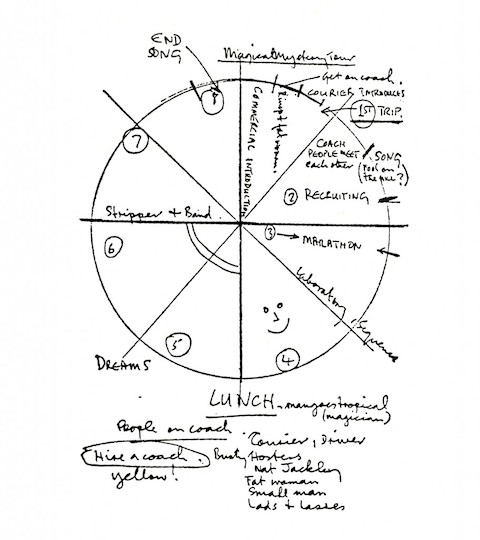

In June 1970, Ellis took a day off, dropped acid at the airport and, “high as a Georgia pine,” checked into a friend’s girlfriend’s house to enjoy the rest of his trip. He woke up two days later, still tripping, went to the stadium, took some stimulants—which “over 90% of the league was using,” he says—and got to work, pitching a no-hitter against the San Diego Padres. “I didn’t see the hitters,” Ellis says, “all I could tell was whether they were on the right side or left side.” Above, his colorful narration gets a full compliment of sound effects and day-glo exclamations. (We also see allusions to Ellis’ other storied antics, like appearing on the mound in curlers and beaning opposing players with fastballs.) “It was easier,” he says, “to pitch with the LSD because I was used to medicating myself.” In this instance at least, the meds were magic.

The short film premiered at Sundance and film festivals worldwide in 2010, and the Dock Ellis legend has only grown since. The same interview become part of Beyond Ellis D, a “multimedia book” for iPads developed in 2012 by Donnell Alexander and animated by Heidi Perry. (See Part 1, “Superfly Spitball,” above.) In an essay for Deadspin, Alexander laments that Ellis—an outspoken critic of racism in baseball—has been largely reduced to the LSD no-hitter, which he calls “a short take on a big life.” While it’s a hell of a good story, Alexander also sees Ellis “on a continuum with Jackie Robinson” (who advised him to tone it down), “a black ballplayer straddling the reserve-clause era and the arrival of free agency, a man who brought many of the old ways with him into baseball’s new, Day-Glo epoch.” Ellis—who died in 2008 of liver failure at age 63 after years as a drug counselor—certainly lived up to the hype. His wild life and career get a full treatment in the documentary No No, which just screened at Sundance this past month. Watch the film’s trailer below.

via The Paris Review

Related Content:

Ken Kesey’s First LSD Trip Animated

Errol Morris’ New Short Film, Team Spirit, Finds Sports Fans Loving Their Teams, Even in Death

This is What Oliver Sacks Learned on LSD and Amphetamines

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness