Last year, we brought you a description of Hunter S. Thompson’s daily drug and alcohol regimen, consisting of frightening amounts of cocaine and liquor, supplanted by the occasional cup of coffee or acid tab. While the story may be apocryphal, Thompson was no dilettante when it came to psychoactive substances. The father of gonzo journalism burnished his image as a formidable substance user in the opening lines of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971):

The trunk of the car looked like a mobile police narcotics lab. We had two bags of grass, seventy—five pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high—powered blotter acid, a salt shaker half full of cocaine, and a whole galaxy of multi—colored uppers, downers, screamers, laughers and also a quart of tequila, a quart of rum, a case of Budweiser, a pint of raw ether and two dozen amyls. All this had been rounded up the night before, in a frenzy of high—speed driving all over Los Angeles County—from Topanga to Watts, we picked up everything we could get our hands on. Not that we needed all that for the trip, but once you get locked into a serious drug collection, the tendency is to push it as far as you can.

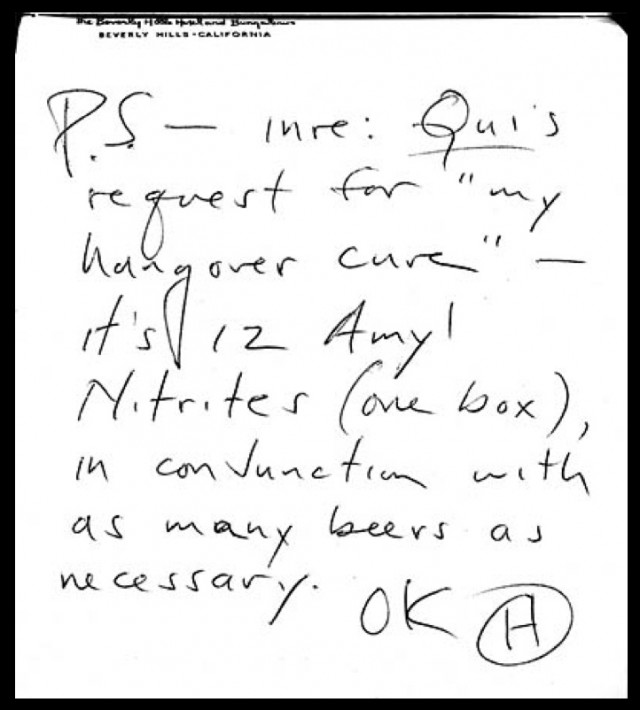

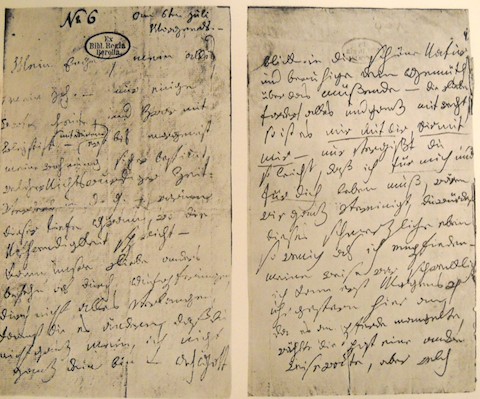

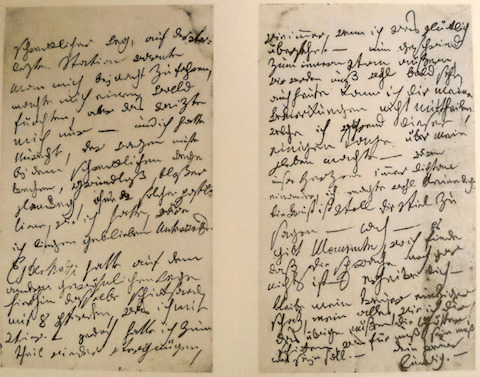

It’s safe to say that if you were to consult anyone about a hangover fix, Thompson would be a good candidate for counsel. Luckily, the author left us with a guide. In 2011, Playboy released a compendium of its 1960s and 1970s correspondences with Thompson. Most were disappointingly prosaic, but among the dross was a hurriedly scribbled note on the topic of hangover cures:

P.S. — inre: Oui’s request for “my hangover cure” — it’s 12 amyl nitrites (one box), in conjunction with as many beers as necessary.

OK H

If a hair of the dog approach doesn’t quite suit you, or if Thompson’s recipe exceeds your initial consumption, I suggest a bottle of sports drink at the tail end of a big night to replenish electrolytes. Still, according YouTube’s SciShow, which does a fantastic job of elucidating the chemical processes behind all the headaches and room spins, there’s only one foolproof method:

As a PSA to stave off angry comments, a spoiler alert: SciShow’s recommendation is on par with the abstinence model of birth control: just don’t do it, and you’ll be fine.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

Hunter S. Thompson Calls Tech Support, Unleashes a Tirade Full of Fear and Loathing (NSFW)

Johnny Depp Reads Letters from Hunter S. Thompson (NSFW)

Hunter S. Thompson Remembers Jimmy Carter’s Captivating Bob Dylan Speech (1974)