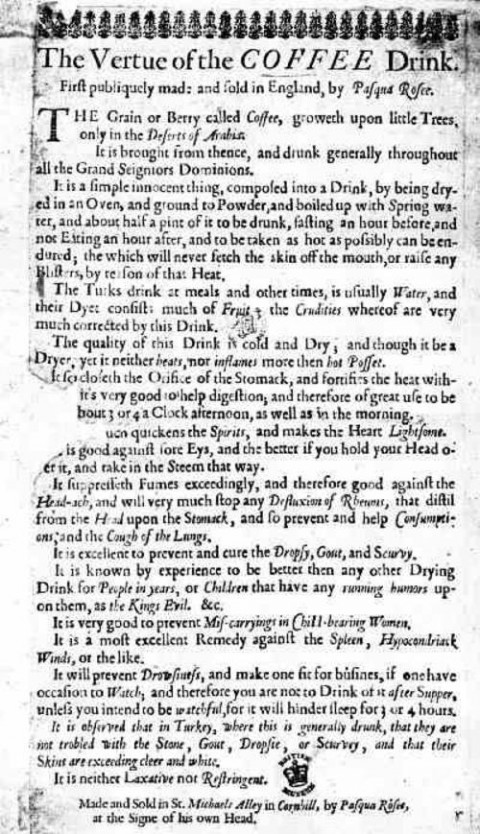

The hallmark of an enduring invention is the difficulty others encounter when attempting to improve on its original design. The QWERTY keyboard is a prime example: since the emergence of the Remington No. 1 typewriter in 1874, the keyboard has confidently withstood any significant challenges. That’s not to say that curious alternatives haven’t occasionally come along. Indeed, several weeks ago we wrote about the Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, the late 19th century typewriter Friedrich Nietzsche used while travelling. Unfortunately, the writing ball proved too fragile and expensive to manufacture, and today survives solely as a relic.

The most unusual recent attempt to reinvent the keyboard was devised by Cy Endfield in the early 1980s. Endfield was a Hollywood director of some success prior to being declared a Communist by Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Commission and blacklisted in 1951. An altogether enterprising fellow, Endfield kept his chin up and his upper lip stiff, opting to head to England where he worked on films (e.g., Zulu, 1964), wrote a book, and performed card tricks with remarkable skill. He also created a six-button word processor he called the Microwriter.

In a 1984 interview with NPR, Endfield recounted wanting to reduce the number of keys used when typing. Instead of pushing a key and obtaining the corresponding letter (a 1‑to‑1 ratio), he wanted to use a handful of keys to yield the whole of the alphabet. He decided that chords were the answer:

“It occurred to me that… it would be possible to combine a set of signals from separate keys, and therefore you could reduce the total number of keys. But, of course, this involved the learning of chords… difficult to memorize… But how do you make these chords memorable? And, one day, staring at a sheet of paper on which I was drawing a set of five keys in sort of the arch formed by the finger ends, it occurred to me, ah! if I press the thumb key, and the index finger key, anybody can do this just listening now, press your thumb key and your index finger down and you’ll see that a vertical line joins those two finger ends, a short vertical line. There is an equivalence between that short vertical line and one letter of the alphabet. It’s the letter “I.”

The above video provides a much simpler and more concise explanation.

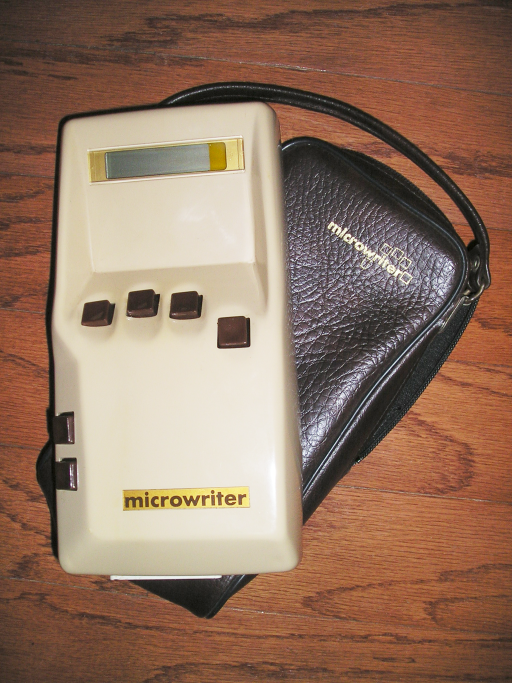

Equipped with 16 kb of RAM and a single line LED display, the Microwriter allowed users to quickly type notes on the go and transfer the results to their computers through the serial port. Five of the buttons corresponded to the various chord-keys, and the lower thumb button allowed users to cycle through various input modes.

While it was possible to achieve a quick pace with the device when typing textual rather than numeric input, users of the device remember needing several days of training to remember the various key combinations and to begin using the device with some proficiency. Needless to say, in spite of Endfield’s claims of being the world’s first portable word processor, the Microwriter simply wasn’t user friendly enough to survive. It entered production in the early 1980s, and ceased in 1985.

To read or listen to Cy Endfield’s full interview, head over to the NPR Archives tumblr.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

Mark Twain Wrote the First Book Ever Written With a Typewriter

The History of the Seemingly Impossible Chinese Typewriter

The Enduring Analog Underworld of Gramercy Typewriter

Discover Friedrich Nietzsche’s Curious Typewriter, the “Malling-Hansen Writing Ball”

Computer Science: Free Online Courses