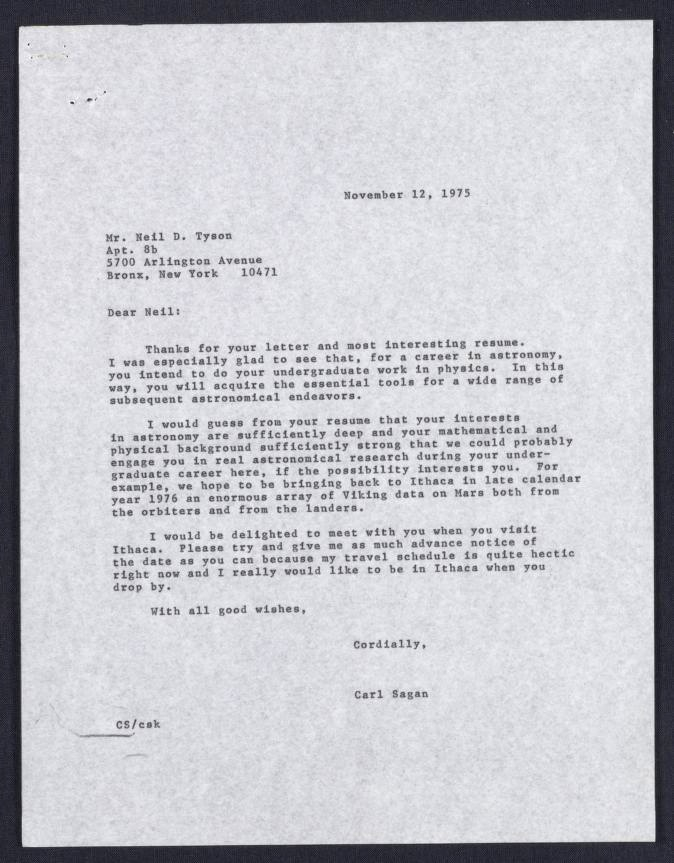

I can vividly recall the first time I read C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. I was fourteen, and I was prepared to be terrified by the book, knowing of its demonic subject matter and believing at the time in invisible malevolence. The novel is written as a series of letters between Screwtape and his nephew Wormwood, two devils tasked with corrupting their human charges, or “patients,” through all sorts of subtle and insidious tricks. The book has a reputation as a literary aid to Christian living—like Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress—but it’s so much more than that. Instead of fire and brimstone, I found ribald wit, sharp satire, a cutting psychological dissection of the modern Western mind, with its evasions, pretensions, and cagey delusions. Stripped of its theology, it might have been written by Orwell or Sartre, though Lewis clearly owes a debt to Kierkegaard, as well as the long tradition of medieval morality plays, with their cavorting devils and didactic human types. Yes, the book is baldly moralistic, but it’s also a brilliant examination of all the twisted ways we fool ourselves and dissemble, or if you like, get led astray by evil forces.

If you haven’t read the book, you can see a concise animation of a critical scene above, one of seven made by “C.S. Lewis Doodle” that illustrate the key points of some of Lewis’s books and essays. Lewis believed in evil forces, but his method of presenting them is primarily literary, and therefore ambiguous and open to many different readings (somewhat like the devil Woland in Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita). The author imagined hell as “something like the bureaucracy of a police state or a thoroughly nasty business office,” a description as chilling as it is inherently comic. As you can see above in the animated scene from Screwtape by C.S. Lewis Doodle, the devils—though drawn in this case as old-fashioned winged fiends—behave like petty functionaries as they lead Wormwood’s solidly middle-class “patient” into the sinister clutches of materialist doctrine by appealing to his intellectual vanity. As much as it’s a condemnation of said doctrine, the scene also works as a critique of a popular discourse that thrives on fashionable jargon and the desire to be seen as relevant and well-read, no matter the truth or coherence of one’s beliefs.

Screwtape was by no means my first introduction to Lewis’s works. Like many, many people, I cut my literary teeth on The Chronicles of Narnia (available on audio here) and his brilliant sci-fi Space Trilogy. But it was the first book of his I’d read that was clearly apologetic in its intent, rather than allegorical. I’m sure I’m not unique among Lewis’s readers in graduating from Screwtape to his more philosophical books and many essays. One such piece, “We Have No (Unlimited) Right to Happiness,” takes on the modern conception of rights as natural guarantees, rather than societal conventions. As he critiques this relatively recent notion, Lewis develops a theory of sexual morality in which “when two people achieve lasting happiness, this is not solely because they are great lovers but because they are also—I must put it crudely—good people; controlled, loyal, fair-minded, mutually adaptable people.” The C.S. Lewis Doodle above illustrates the many examples of fickleness and inconstancy that Lewis presents in his essay as foils for the virtues he espouses.

The Lewis Doodle seen here illustrates his 1948 essay “On Living in an Atomic Age,” in which Lewis chides readers for the panic and paranoia over the impending threat of nuclear war in the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Such an occurrence, he writes, would only result in the already inevitable—death—just as the plagues of the sixteenth century or Viking raids:

This is the first point to be made: and the first action to be taken is to pull ourselves together. If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things — praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts — not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds.

It seems a very mature, and noble, perspective, but if you think that Lewis glibly glosses over the substantively different effects of a nuclear age from any other—fallout, radiation poisoning, the end of civilization itself—you are mistaken. His answer, however, you may find as I do deeply fatalistic. Lewis questions the value of civilization altogether as a hopeless endeavor bound to end in any case in “nothing.” “Nature is a sinking ship,” he writes, and dooms us all to annihilation whether we hasten the end with technology or manage to avoid that fate. Here is Lewis the apologist, presenting us with the starkest of options—either all of our endeavors are utterly meaningless and without purpose or value, since we cannot make them last forever, or all meaning and value reside in the theistic vision of existence. I’ve not myself seen things Lewis’s way on this point, but the C.S. Lewis Doodler does, and urges his viewers who agree to “send to your enquiring atheistic mates” his lovely little adaptations. Or you can simply enjoy these as many non-religious readers of Lewis enjoy his work—take what seems beautiful, humane, true, and skillfully, lucidly written (or drawn), and leave the rest for your enquiring Christian mates.

You can watch all seven animations of C.S. Lewis’s writings here.

Related Content:

C.S. Lewis’ Prescient 1937 Review of The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien: It “May Well Prove a Classic”

Free Audio: Download the Complete Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis

18 Animations of Classic Literary Works: From Plato and Shakespeare, to Kafka, Hemingway and Gaiman

Watch Animations of Oscar Wilde’s Children’s Stories “The Happy Prince” and “The Selfish Giant”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.