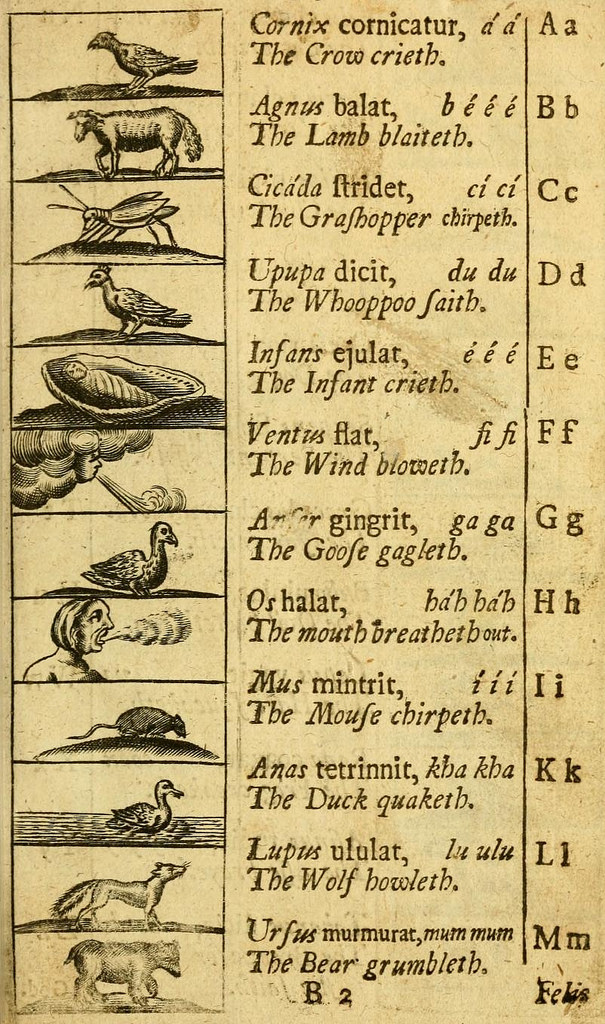

I’ve heard a fair few new parents agonizing about what children’s books to admit into the family canon. Many of the same names keep coming up: 1947’s Goodnight Moon, 1969’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar, 1977’s Everyone Poops — classics, all. Oddly, I’ve never heard any of them mention the earliest known children’s book, 1658’s Orbis Sensualium Pictus, or The World of Things Obvious to the Senses Drawn in Pictures. “With its 150 pictures showing everyday activities like brewing beer, tending gardens, and slaughtering animals,” writes Charles McNamara at The Public Domain review, the Orbis looks “immediately familiar as an ancestor of today’s children’s literature. This approach centered on the visual was a breakthrough in education for the young. [ … ] Unlike treatises on education and grammatical handbooks, it is aimed directly at the young and attempts to engage on their level.” In other words, its author, Czech-born school reformer John Comenius, accomplishes that still-rare feat of writing not down to children, but straight at them — albeit in Latin.

The Orbis holds not just the status of the first children’s book, but the first megahit in children’s publishing, receiving translations in a great many languages and becoming the most popular elementary textbook in Europe. It opens with a sentence that, in McNamara’s words, “would seem peculiar in today’s children’s books: ‘Come, boy, learn to be wise.’ We see above a teacher and student in dialogue, the former holding up his finger and sporting a cane and large hat, the latter listening in an emotional state somewhere between awe and anxiety. The student asks, ‘What doth this mean, to be wise?’ His teacher answers, ‘To understand rightly, to do rightly, and to speak out rightly all that are necessary.’ ” This leads into something like “an early version of ‘Old MacDonald Had a Farm,’ ” lessons on “the philosophical and the invisible,” “thirty-five chapters on theology, elements, plants, and animals,” and finally, an “extensive discussion” of religion which ends with “an admonition not to go out into the world at all.” After reading the Orbis, embedded in full at the top of this post, you can judge for yourself whether it belongs on the shelf. Perhaps you could file it alongside Richard Scarry’s Busytown books?

Related Content:

The International Children’s Digital Library Offers Free eBooks for Kids in Over 40 Languages

The Epistemology of Dr. Seuss & More Philosophy Lessons from Great Children’s Stories

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.