We humans have relied on the deceptively humble button since its first appearance in the Indus Valley some 5000 years ago.

In the pre-zipper era, what better way to show off your shapely arms or calves than a row of gorgeous and functional buttons?

Need to pay a debt, or bestow a love token on a fetching suitor? Pluck a button from your garment, and consider the matter closed.

The first campaign buttons? Actual buttons! Thanks, George Washington!

It is, as Charles Dickens noted, following a visit to a Birmingham button factory, “a serious thing to attempt to learn about buttons.” It should come as no surprise that the great champion of the oppressed not only did his homework, but wound up having rather a lot to say on the subject.

Judging by his account of what he witnessed in Birmingham, most would assume that the button-making process requires specialized machinery, a number of specialized materials, and a large, nimble-fingered workforce.

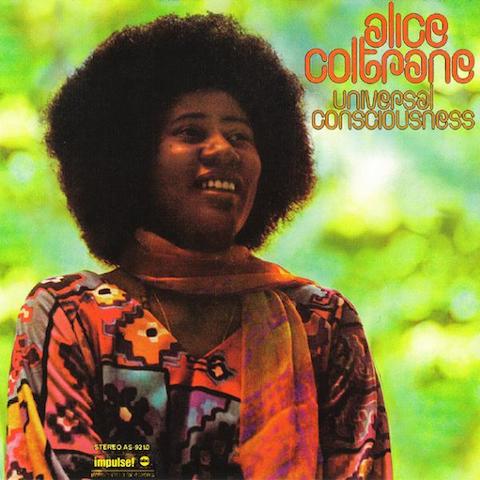

Not so, as filmmaker Miranda July demonstrates in the extremely illuminating how-to video, above.

Yes, certain steps will require a high degree of concentration. Don’t expect to successfully Ferberize—or in layman’s terms, put holes in—your buttons on the first attempt. Stick with it, though. Even an experienced fabricant de bouton like July will occasionally have trouble with things like granular compounds and high voltage hardeners.

As a newcomer to the exciting world of button-making, I really appreciated July’s clear, step-by-step instruction, as well as her encouraging vibe. The project requires a degree of skill and patience that may elude younger viewers, but I can attest that my 13-year-old son was absolutely riveted throughout. He may never produce any buttons, but he can’t wait to share his newfound knowledge with all his friends!

In closing, let us revisit Dickens, whose enthusiasm lives on in July, a fellow writer and Aquarian, 162 years his junior:

It is wonderful, is it not? that on that small pivot turns the fortune of such multitudes of men, women, and children, in so many parts of the world; that such industry, and so many fine faculties, should be brought out and exercised by so small a thing as the Button.

Related Content:

Watch Miranda July’s Short Film on Avoiding the Pitfalls of Procrastination

David Sedaris Reads You a Story By Miranda July

Ayun Halliday is the author of seven books, and creator of the award winning East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday