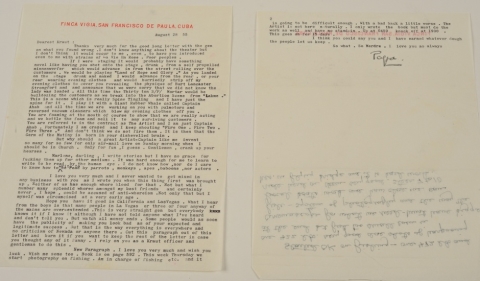

Click to enlarge

We think today of Ernest Hemingway as that most stylistically disciplined of writers, but it seems that, outside his published work and especially in his personal correspondence, he could cut pretty loose. One particularly vivid example has returned to public attention recently by appearing for sale on a site called auctionmystuff.com: a letter from Hemingway to legendary singer-actress Marlene Dietrich, dated August 28, 1955. “In the intimate, rambling and revealing letter,” writes the Wall Street Journal’s Jonathan Welsh, “Hemingway professes his love for Dietrich a number of times, though the two are said to have never consummated the relationship.” He also, Welsh notes, “talks about staging one of her performances, in which he imagines her ‘drunk and naked.’ ” The full letter, which spares no detail of this elaborate fantasy, runs as follows:

Dearest Kraut :

Thanks very much for the good long letter with the gen on what you found wrong. I don’t know anything about the theater but I don’t think it would occur to me, even, to have you introduced even to me with strains of La Vie En Rose. Poor peoples.

If I were staging it would probably have something novel like having you shot onto the stage, drunk, from a self-propelled minnenwerfer which would advance in from the street rolling over the customers. We would be playing “Land of Hope and Glory.” As you landed on the stage drunk and naked I would advance from the rear, or from your rear wearing evening clothes and would hurriedly strip off my evening clothes to cover you revealing the physique of Burt Lancaster Strongfort and announce that we were sorry that we did not know the lady was loaded. All this time the Thirty ton S/P/ Mortar would be bulldozing the customers as we break into the Abortion Scene from “Lakme.” This is a scene which is really Spine Tingling and I have just the spine for it. I play it with a Giant Rubber Whale called Captain Ahab and all the time we are working on you with pulmotors and raversed (sic) cleaners which blow my evening clothes off you. You are foaming at the mouth of course to show that we are really acting and we bottle the foam and sell it to any surviving customers. You are referred to in the contract as The Artist and I am just Captain Ahab. Fortunately I am crazed and I keep shouting “Fire One. Fire Two. Fire Three.” And don’t think we do not fire them. It is then that the Germ of the Mutiny is born in your disheveled brain.

But why should a great Artist-Captain like me invent so many for so few for only air-mail love on Sunday morning when I should be in church. Only for fun, I guess. Gentlemen, crank up your hearses.

Marlene, darling, I write stories but I have no grace for fucking them up for other mediums. It was hard enough for me to learn to write to be read by the human eye. I do not know how, nor do I care to know how to write to be read by parrots, monkeys, apes, baboons, nor actors.

I love you very much and I never wanted to get mixed in any business with you as I wrote you when this thing first was brought up. Neither of us has enough whore blood for that. Not but what I number many splendid whores amongst my best friends and certainly never, I hope, could be accused of anti-whoreism. Not only that but I was circumcised as a very early age.

Hope you have it good in California and Las Vegas. What I hear from the boys is that many people in La Vegas (sic) or three or four anyway of the mains are over-extended. This is very straightgen but everybody knows it if I know it although I have not told anyone what I’ve heard and don’t tell you. But watch all money ends. Some people would as soon have the publicity of making you look bad as of your expected and legitimate success. But that is the way everything is everywhere and no criticism of Nevada or anyone there. Cut this paragraph out of this letter and burn it if you want to keep the rest of the letter in case you thought any of it funny. I rely on you as a Kraut officer and gentlemen do this.

New Paragraph. I love you very much and wish you luck. Wish me some too. Book is on page 592. This week Thursday we start photography on fishing. Am in charge of fishing etc. and it is going to be difficult enough. With a bad back a little worse. The Artist is not here naturally. I only wrote the book but must do the work as well and have no stand-in. Up at 0450 knock off at I930. This goes on for I5 days.

I think you could say you and I have earned whatever dough the people let us keep.

So what. So Merdre. I love you as always.

Papa

“To him she was ‘my little Kraut,’ or ‘daughter,’ to her he was simply ‘Papa’ — and it was love at first sight when they met aboard a French ocean liner in 1934,” writes The Guardian’s Kate Connolly of the two icons’ unusual relationship. “Hemingway and Dietrich started writing to each other when he was 50 and she was 47, remaining in close contact until the writer’s suicide in 1961. But they never consummated their love, because of what Hemingway referred to as ‘unsynchronised passion.’ ” A fan of both Hemingway and Dietrich could presumably desire nothing more than one of the original pieces of their correspondence, but this particular letter, with a starting price of $35,000, drew not a single bid — perhaps a sale, like the physical expression of the Old Man and the Sea author and “Lili Marleen” singer’s love, fated never to happen.

Related Content:

Marlene Dietrich’s Tempermental Screen Test for The Blue Angel (and the Complete 1930 Film)

Ernest Hemingway to F. Scott Fitzgerald: “Kiss My Ass”

Ernest Hemingway’s Favorite Hamburger Recipe

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.