Unlikely collaborations in pop music abound: Run DMC and Aerosmith? It works! U2 and Luciano Pavarotti? Why not? Robert Plant and Alison Krauss? Sure! Anyone and Kermit the Frog? Yes. They don’t always work out, but the attempts, whether kismet or trainwreck, tend to reveal a great deal about the partners’ strengths and weaknesses. Unlikely collaborations in feature film are somewhat rarer, though not for lack of wishing. I would guess the high financial stakes have something to do with this, as well as the sheer number of people required for the average production. One particularly salient example of an ostensible mismatch in animated movies—a planned co-creation by surrealist Salvador Dalí and populist Walt Disney—offers a fascinating look at how the two artists’ careers could have taken very different creative directions. The collaboration may also have fallen victim to a film industry whose economics discourage experimental duets.

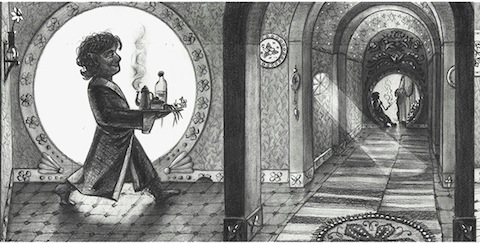

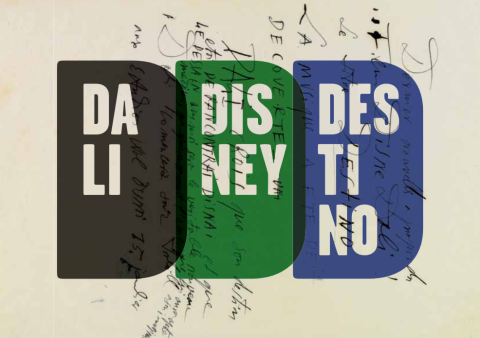

We’ve previously featured the animated short— Destino—at the top of the post. The 6 and a half minute film shows us what Dalí and Disney’s planned project might have looked like. Recreated from 17 seconds of original animation and storyboards drawn by Dalí and released in 2003 by Disney’s nephew Roy, Destino gives us an almost perfect symbiosis of the two creators’ sensibilities, with Walt Disney’s Fantasia-like flights smoothly animating Dalí’s fluid dream imagery. According to Chris Pallant, author of Demystifying Disney, work between the two on the original project also moved smoothly, with little friction between the two artists. Meeting in 1945, Dalí and Disney “quickly developed an industrious working relationship” and “ease of collaboration.” Pallant writes that “Disney’s desire for absolute creative control changed, and, for the first time, the animators working within the studio felt the influence of other artistic forces.” I imagine it might prove difficult, if not impossible, to micromanage Salvador Dalí. In any case, the fruitful relationship produced results:

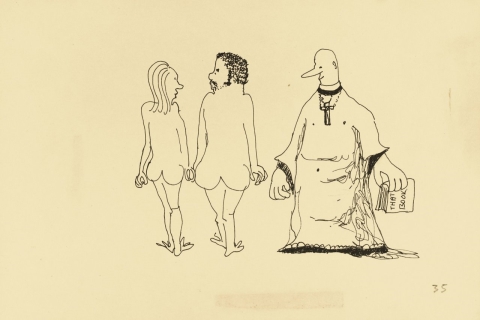

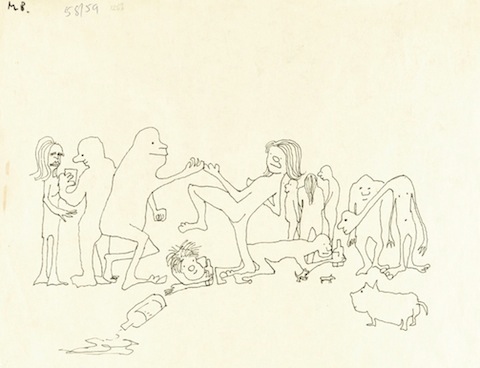

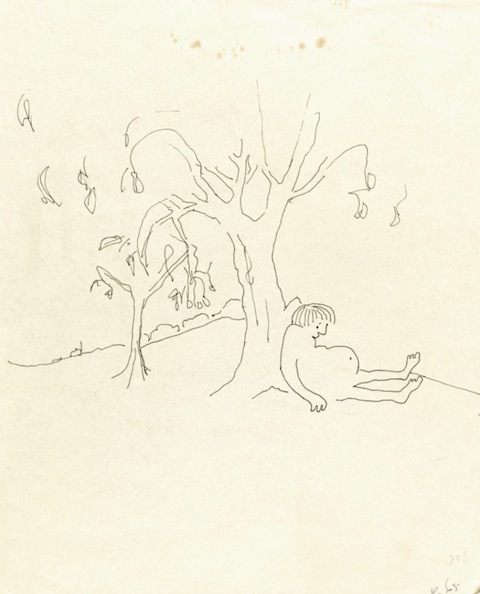

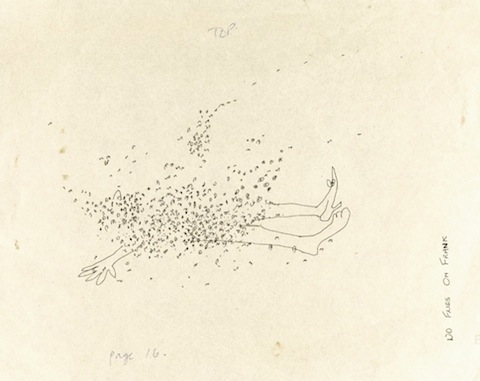

Destino reached a relatively advanced stage before being abandoned. By mid-1946 the Disney- Dalí collaboration encompassed approximately ’80 pen-and-ink sketches’ and numerous ‘storyboards, drawings and paintings that were created over nine months in 1945 and 1946.’

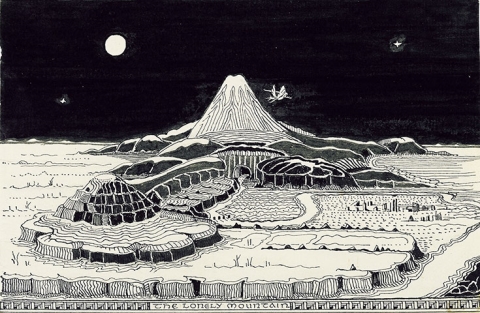

Roy E. Disney discovered Dalí’s Destino artwork in the late 90s, leading to his short re-creation of what might have been. Above, you can flip through a slideshow of twelve of those drawings and storyboards, courtesy of Park West Gallery, who represent the work. The Destino materials went on display at the Drawings Room in Figueres, Spain. The exhibition featured “1 oil painting, 1 watercolour, 15 preparatory drawings—10 of which are unpublished—and 9 photographs of Dalí in the creative process of this material, of the Disney couple in Port Lligat in 1957, and the Dalí couple in Burbank.” You can see many of those photographs in the exhibit’s pamphlet (in pdf here, in Spanish and English; cover image below), which offers a detailed description of the original project, including its narrative concept, a “love story” between a dancer and “baseball-player-cum-god Cronos” meant to represent “the importance of time as we wait for destiny to act on our lives.”

Inspired by a Mexican song by Armando Dominguez, Destino, on its face, seems like a very strange choice for Disney, who generally trafficked in more recognizable (and European) folk-tale sources. And yet, the exhibition pamphlet asserts, the co-production made a great deal of sense for Dalí, “if we consider that one Dalinian constant is his bringing together of the elitist artistic idea and mass culture (and vice versa) […]. Destino becomes a unique artistic product in which Dalinian expressiveness is combined with Disney’s fantasy and sonority, making it a film in which Dalí’s images take on movement and Disney’s figures become ‘Dalinised.’ ”

And yet, while both Dalí and Disney worked excitedly on the project, it was ultimately not to be, at least until almost sixty years later. Destino would have been part of a “package film,” like Fantasia, a compilation of short vignettes. John Hench, a Disney artist who worked on the project with Dalí, speculated that the company “foresaw the end” of such features. Pallant, however, goes further in speculating the film “would have resembled a potential box-office bomb” for Disney, who remarked later that is was “no fault of Dalí’s that the project… was not completed—it was simply a case of policy changes in our distribution plans.”

This cryptic remark, writes Pallant, alludes to Disney’s plans to focus his creative energy on “safe” feature-length projects “to strengthen the company’s position within the film industry.” While such a decision might have made good business sense, it probably doomed many more Destino-like ideas that might have made the Walt Disney company a very different entity indeed. One can only imagine what the studio might have become had Disney opted to pursue experiments like this instead of taking the more profitable route. Of course, given the market pressures on the movie industry, it’s also possible the studio might not have survived at all.

Related Content:

Destino: The Salvador Dalí – Disney Collaboration 57 Years in the Making

Alfred Hitchcock Recalls Working with Salvador Dali on Spellbound

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.