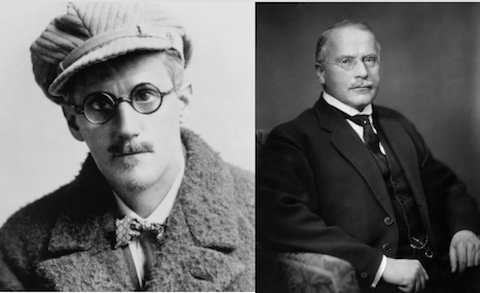

Feelings about James Joyce’s Ulysses tend to fall roughly into one of two camps: the religiously reverent or the exasperated/bored/overwhelmed. As popular examples of the former, we have the many thousand celebrants of Bloomsday—June 16th, the date on which the novel is set in 1904. These revelries approach the level of saints’ days, with re-enactments and pilgrimages to important Dublin sites. On the other side, we have the reactions of Virginia Woolf, say, or certain friends of mine who left wry comments on Bloomsday posts about picking up something more “readable” to celebrate. (A third category, the scandalized, has more or less died off, as scatology, blasphemy, and cuckoldry have become the stuff of sitcoms.) Another famous reader, Carl Jung, seems at first to damn the novel with some faint praise and much scathing criticism in a 1932 essay for Europäische Revue, but ends up, despite himself, writing about the book in the language of a true believer.

A great many readers of Jung’s essay may perhaps nod their heads at sentences like “Yes, I admit I feel I have been made a fool of” and “one should never rub the reader’s nose into his own stupidity, but that is just what Ulysses does.” To illustrate his boredom with the novel, he quotes “an old uncle,” who says “’Do you know how the devil tortures souls in hell? […] He keeps them waiting.’” This remark, Jung writes, “occurred to me when I was plowing through Ulysses for the first time. Every sentence raises an expectation which is not fulfilled; finally, out of sheer resignation, you come to expect nothing any longer.” But while Jung’s critique may validate certain hasty readers’ hatred of Joyce’s nearly unavoidable 20th century masterwork, it also probes deeply into why the novel resonates.

For all of his frustration with the book—his sense that it “always gives the reader an irritating sense of inferiority”—Jung nonetheless bestows upon it the highest praise, comparing Joyce to other prophetic European writers of earlier ages like Goethe and Nietzsche. “It seems to me now,” he writes, “that all that is negative in Joyce’s work, all that is cold-blooded, bizarre and banal, grotesque and devilish, is a positive virtue for which it deserves praise.” Ulysses is “a devotional book for the object-besotted white man,” a “spiritual exercise, an aesthetic discipline, an agonizing ritual, an arcane procedure, eighteen alchemical alembics piled on top of one another […] a world has passed away, and is made new.” He ends the essay by quoting the novel’s entire final paragraph. (Find longer excerpts of Jung’s essay here and here.)

Jung not only wrote what may be the most critically honest yet also glowing response to the novel, but he also took it upon himself in September of 1932 to send a copy of the essay to the author along with the letter below. Letters of Note tells us that Joyce “was both annoyed and proud,” a fittingly divided response to such an ambivalent review.

Dear Sir,

Your Ulysses has presented the world such an upsetting psychological problem that repeatedly I have been called in as a supposed authority on psychological matters.

Ulysses proved to be an exceedingly hard nut and it has forced my mind not only to most unusual efforts, but also to rather extravagant peregrinations (speaking from the standpoint of a scientist). Your book as a whole has given me no end of trouble and I was brooding over it for about three years until I succeeded to put myself into it. But I must tell you that I’m profoundly grateful to yourself as well as to your gigantic opus, because I learned a great deal from it. I shall probably never be quite sure whether I did enjoy it, because it meant too much grinding of nerves and of grey matter. I also don’t know whether you will enjoy what I have written about Ulysses because I couldn’t help telling the world how much I was bored, how I grumbled, how I cursed and how I admired. The 40 pages of non stop run at the end is a string of veritable psychological peaches. I suppose the devil’s grandmother knows so much about the real psychology of a woman, I didn’t.

Well, I just try to recommend my little essay to you, as an amusing attempt of a perfect stranger that went astray in the labyrinth of your Ulysses and happened to get out of it again by sheer good luck. At all events you may gather from my article what Ulysses has done to a supposedly balanced psychologist.

With the expression of my deepest appreciation, I remain, dear Sir,

Yours faithfully,

C. G. Jung

With this letter of introduction, Jung was “a perfect stranger” to Joyce no longer. In fact, two years later, Joyce would call on the psychologist to treat his daughter Lucia, who suffered from schizophrenia, a tragic story told in Carol Loeb Schloss’s biography of the novelist’s famously troubled child. For his care of Lucia and his careful attention to Ulysses, Joyce would inscribe Jung’s copy of the book: “To Dr. C.G. Jung, with grateful appreciation of his aid and counsel. James Joyce. Xmas 1934, Zurich.”

via Letters of Note

Related Content:

Everything You Need to Enjoy Reading James Joyce’s Ulysses on Bloomsday

The Very First Reviews of James Joyce’s Ulysses: “A Work of High Genius” (1922)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness