The CIA fought most of the Cold War on the cultural front, recruiting operatives and placing agents in every possible sphere of influence, not only abroad but at home as well. As Francis Stoner Saunders’ book The Cultural Cold War: the CIA and the World of Arts and Letters details, the agency funded intellectuals across the political spectrum as well as producers of radio, TV, and film. A well-financed propaganda campaign aimed at the American public attempted to persuade the populace that their country looked exactly like its leaders wished to see it, a well-run capitalist machine with equal opportunity for all. In addition to the agency’s various forays into jazz and modern art, the CIA also helped finance and consulted on the production of animated films, like the 1954 adaptation of George Orwell’s Animal Farm we recently featured. We’ve also posted on other animated propaganda films made by government agencies, such as A is for Atom, a PR film for nuclear energy, and Duck and Cover, a short suggesting that cleanliness may help citizens survive a nuclear war.

Today we bring you three short animations funded and commissioned by private interests. These films were made for Arkansas’ Harding College (now Harding University) and financed by longtime General Motors CEO Alfred P. Sloan. The name probably sounds familiar. Today the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation generously supports public radio and television, as well as medical research and other altruistic projects. In the post-war years, Sloan, widely considered “the father of the modern corporation,” writes Karl Cohen in a two-part essay for Animation World Network, supposedly took a shine to the bootstrapping president of Harding, George S. Benson, a Christian missionary and crusading anti-Communist who used his position to promote God, family, and country. According to Cohen, Sloan donated several hundred thousand dollars to Harding as funding for “educational anti-Communist, pro-free enterprise system films.” Contracted by the college, producer John Sutherland, former Disney writer, made nine films in all. As you’ll see in the title card that opens each short, these were ostensibly made “to create a deeper understanding of what has made America the finest place in the world to live.” At the top, watch 1949’s “Why Play Leap Frog?” and just above, see another of the Harding films, “Meet King Joe,” also from 1949.

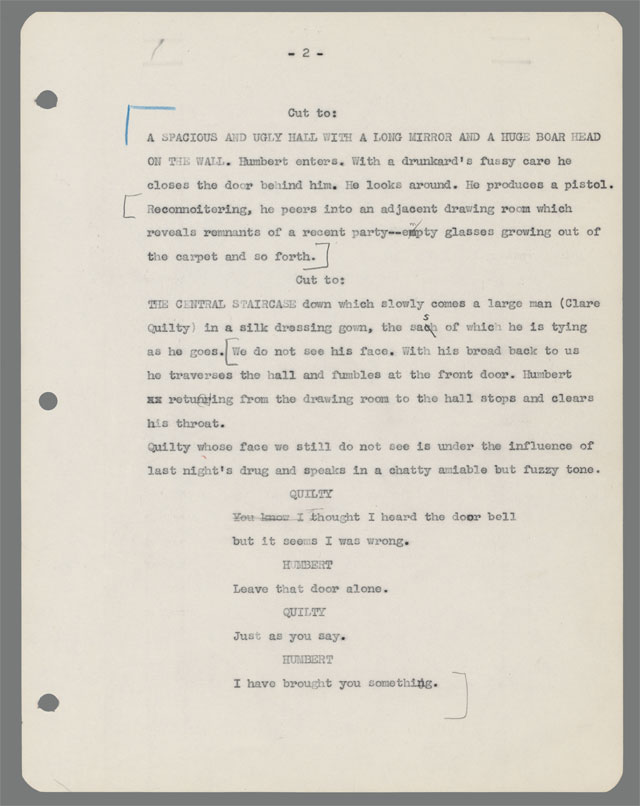

Just above, watch a third of the Harding propaganda films, “Make Mine Freedom,” from 1948. Each of these films, calling themselves “Fun and Facts about America,” present simplistic patriotic stories with an authoritative narrator who patiently explains the ins and outs of American exceptionalism. “Why Play Leapfrog?” tells the story of Joe, a disgruntled doll-factory worker who learns some important lessons about the supply chain, wages, and prices. He also learns that he’d better work harder to increase his productivity (and cooperate with management) if he wants to keep up with the rising cost of living. “Meet King Joe” introduces us to the “king of the workers of the world,” so called because he can buy more stuff than the poor schlubs in other countries. Joe, “no smarter” and “no stronger than workers in other lands” has such advantages only because of, you guessed it, the wonders of capitalism. “Make Mine Freedom” reminds viewers of their Constitutional rights before introducing us to a snake oil charlatan selling “ism,” a Commie-like tonic, to a group of U.S. labor disputants—if only they’ll sign over their rights and property. The assembled crowd jumps at the chance, but then along comes John Q. Public, who won’t give up his freedom for “some imported double-talk.”

You can read much more about the relationship between Sloan and Benson and the other films Sutherland produced with Sloan’s money, in Cohen’s essay, which also includes information on Cold War animated propaganda films made by Warner Brothers and Disney.

Related Content:

Animal Farm: Watch the Animated Adaptation of Orwell’s Novel Funded by the CIA (1954)

A is for Atom: Vintage PR Film for Nuclear Energy

How a Clean, Tidy Home Can Help You Survive the Atomic Bomb: A Cold War Film from 1954

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness