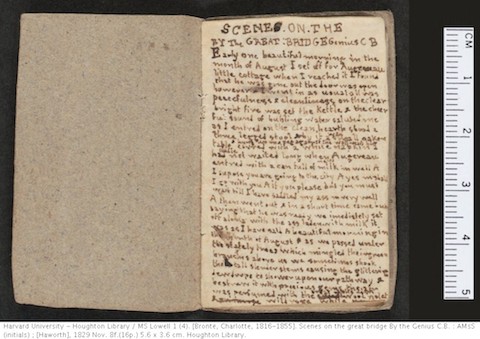

So you consider yourself a reader of the Brontës? Of course you’ve read Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. (Find these classics in our collection of Free eBooks and Free Audio Books.) You’ve probably even got on to the likes of The Green Dwarf and Agnes Grey. Surely you know details from the lives of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne. But have you read such lesser-known entries in the Brontë canon as Scenes on a Great Bridge, The Poetaster: A Drama in Two Volumes, or An Interesting Passage in the Lives of Some Eminent Personages of the Present Age? Do you know of Brontë brother Branwell, the ill-fated tutor, clerk, and artist, and have you seen his own literary output? Now you can, as Harvard University’s Houghton Library has put online nine very early works from Charlotte and Branwell Brontë — all of which measure less than one inch by two inches.

“In 1829 and 1830,” writes Harvard Library Communications’ Kate Kondayen, “Charlotte and Branwell cobbled pages together from printed waste and scrap paper, perhaps cut from margins of discarded pamphlets,” producing “tiny, hand-lettered, hand-bound books” in which “page after mini-page brims with poems, stories, songs, illustrations, maps, building plans, and dialogue. The books, lettered in minuscule, even script, tell of the ‘Glass Town Confederacy,’ a fictional world the siblings created for and around Branwell’s toy soldiers, which were both the protagonists of and audience for the little books.” A dedicated Brontë aficionado may settle for nothing less than seeing these in person, but a reader more interested in the avoidance of eyestrain will certainly prefer to read these digitally magnifiable editions on the web. The hat tip for these miniscule treasures of literary juvenalia goes to the Los Angeles Times’ Carolyn Kellogg, who provides a list of links to the individual works:

By Charlotte Brontë:

Scenes on the great bridge, November 1829

The silver cup: a tale, October 1829

Blackwoods young mens magazine, August 1829

An interesting passage in the lives of some eminent personages of the present age, June 1830

The poetaster: a drama in two volumes, July 1830

The adventures of Mon. Edouard de Crack, February 1830

By Patrick Branwell Brontë:

Branwells Blackwoods magazine, June 1829

Magazine, January 1829

Branwells Blackwoods magazine, July 1829

Related Content:

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.