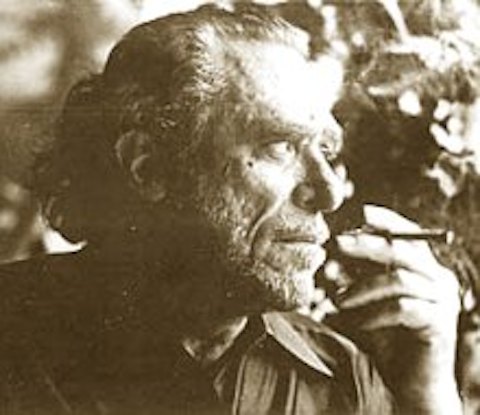

Charles Bukowski—or “Hank” to his friends—assiduously cultivated a literary persona as a perennial drunken deadbeat. He mostly lived it too, but for a few odd jobs and a period of time, just over a decade, that he spent working for the United States Post Office, beginning in the early fifties as a fill-in letter carrier, then later for over a decade as a filing clerk. He found the work mind-numbing, soul-crushing, and any number of other adjectives one uses to describe repetitive and deeply unfulfilling labor. Actually, one needn’t supply a description—Bukowski has splendidly done so for us, both in his fiction and in the epistle below unearthed by Letters of Note.

In Bukowski’s first novel Post Office (1971), the writer of lowlife comedy and pathos builds in plenty of wish-fulfillment for his literary alter ego Henry Chinaski. Kyle Ryan at The Onion’s A.V. Club sums it up succinctly: “In Bukowski’s world, Chinaski is practically irresistible to women, despite his alcoholism, misogyny, and general crankiness.” In reality, to say that Bukowski found little solace in his work would be a gross understatement. But unlike most of his equally miserable co-workers, Bukowski got to retire early, at age 49, when, in 1969, Black Sparrow Press publisher John Martin offered him $100 a month for life on the condition that he quit his job and write full time.

Needless to say, he was thrilled, so much so that he penned the letter below fifteen years later, expressing his gratitude to Martin and describing, with characteristic brutal honesty, the life of the average wage slave. And though comparisons to slavery usually come as close to the level of absurd exaggeration as comparisons to Nazism, Bukowski’s portrait of the 9 to 5 life makes a very convincing case for what we might call the thesis of his letter: “Slavery was never abolished, it was only extended to include all the colors.”

After reading his letter below, you may feel a great deal more sympathy, if you did not already, with Bukowski’s life choices. You may find yourself, in fact, re-evaluating your own.

8–12-86

Hello John:

Thanks for the good letter. I don’t think it hurts, sometimes, to remember where you came from. You know the places where I came from. Even the people who try to write about that or make films about it, they don’t get it right. They call it “9 to 5.” It’s never 9 to 5, there’s no free lunch break at those places, in fact, at many of them in order to keep your job you don’t take lunch. Then there’s OVERTIME and the books never seem to get the overtime right and if you complain about that, there’s another sucker to take your place.

You know my old saying, “Slavery was never abolished, it was only extended to include all the colors.”

And what hurts is the steadily diminishing humanity of those fighting to hold jobs they don’t want but fear the alternative worse. People simply empty out. They are bodies with fearful and obedient minds. The color leaves the eye. The voice becomes ugly. And the body. The hair. The fingernails. The shoes. Everything does.

As a young man I could not believe that people could give their lives over to those conditions. As an old man, I still can’t believe it. What do they do it for? Sex? TV? An automobile on monthly payments? Or children? Children who are just going to do the same things that they did?

Early on, when I was quite young and going from job to job I was foolish enough to sometimes speak to my fellow workers: “Hey, the boss can come in here at any moment and lay all of us off, just like that, don’t you realize that?”

They would just look at me. I was posing something that they didn’t want to enter their minds.

Now in industry, there are vast layoffs (steel mills dead, technical changes in other factors of the work place). They are layed off by the hundreds of thousands and their faces are stunned:

“I put in 35 years…”

“It ain’t right…”

“I don’t know what to do…”

They never pay the slaves enough so they can get free, just enough so they can stay alive and come back to work. I could see all this. Why couldn’t they? I figured the park bench was just as good or being a barfly was just as good. Why not get there first before they put me there? Why wait?

I just wrote in disgust against it all, it was a relief to get the shit out of my system. And now that I’m here, a so-called professional writer, after giving the first 50 years away, I’ve found out that there are other disgusts beyond the system.

I remember once, working as a packer in this lighting fixture company, one of the packers suddenly said: “I’ll never be free!”

One of the bosses was walking by (his name was Morrie) and he let out this delicious cackle of a laugh, enjoying the fact that this fellow was trapped for life.

So, the luck I finally had in getting out of those places, no matter how long it took, has given me a kind of joy, the jolly joy of the miracle. I now write from an old mind and an old body, long beyond the time when most men would ever think of continuing such a thing, but since I started so late I owe it to myself to continue, and when the words begin to falter and I must be helped up stairways and I can no longer tell a bluebird from a paperclip, I still feel that something in me is going to remember (no matter how far I’m gone) how I’ve come through the murder and the mess and the moil, to at least a generous way to die.

To not to have entirely wasted one’s life seems to be a worthy accomplishment, if only for myself.

yr boy,

Hank

via Flavorwire

Related Content:

Charles Bukowski: Depression and Three Days in Bed Can Restore Your Creative Juices (NSFW)

“Don’t Try”: Charles Bukowski’s Concise Philosophy of Art and Life

The Last (Faxed) Poem of Charles Bukowski

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness