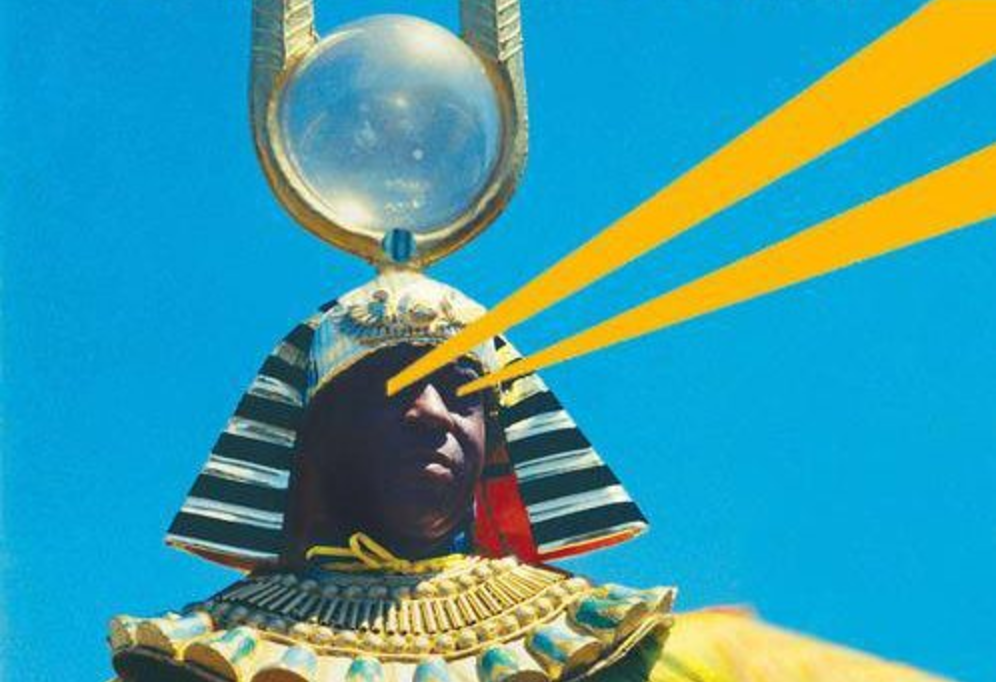

A pioneer of “Afrofuturism,” bandleader Sun Ra emerged from a traditional swing scene in Alabama, touring the country in his teens as a member of his high school biology teacher’s big band. While attending Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University, he had an out-of-body experience during which he was transported into outer space. As biographer John Szwed records him saying, “my whole body changed into something else. I landed on a planet that I identified as Saturn.” While there, aliens with “little antenna on each ear. A little antenna on each eye” instructed him to drop out of college and speak through his music. And that’s just what he did, changing his name from Herman Blount and never looking back.

Whether you believe that story, whether Sun Ra believes it, or whether his entire persona is a theatrical put-on should make no difference. Because Sun Ra would be a visionary either way. Combining Afrocentric science fiction, esoteric and occult philosophy, Egyptology, and, with his “Arkestra,” his own brand of free jazz-futurism that has no equal on earth, the man is truly sui generis. In 1971, he served as artist-in-residence at UC Berkeley and offered a spring semester lecture, African-American Studies 198, also known as “Sun Ra 171,” “The Black Man in the Universe,” or “The Black man in the Cosmos.” The course featured readings from—to name just a few—theosophist Madame Blavatsky, French philosopher Constantin Francois de Chasseboeuf, black American writer and poet Henry Dumas, and “God,” whom the cosmic jazz theorist reportedly listed as the author of The Source Book of Man’s Life and Death (otherwise known as the King James Bible).

Now we have the rare opportunity to hear a full lecture from that class, thanks to Ubu.com. Listen to Sun Ra spin his intricate, bizarrely otherworldly theories, drawn from his personal philosophy, peculiar etymologies, and idiosyncratic readings of religious texts. Hearing him speak is a little like hearing him play, so be prepared for a lot of free association and jarring, unexpected juxtapositions. Szwed describes a “typical lecture” below:

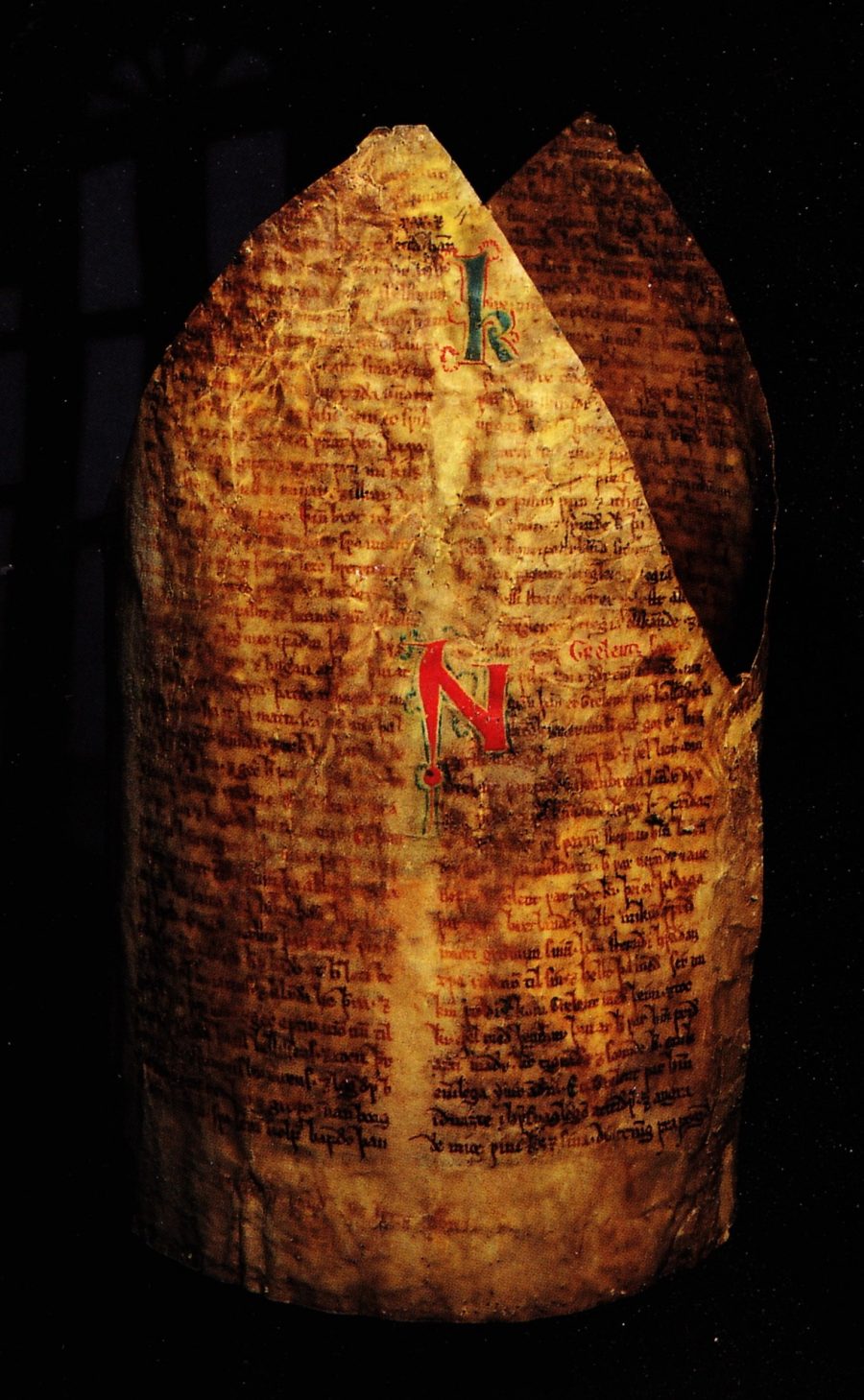

Sun Ra wrote biblical quotes on the board and then ‘permutated’ them—rewrote and transformed their letters and syntax into new equations of meaning, while members of the Arkestra passed through the room, preventing anyone from taping the class. His lecture subjects included Neoplatonic doctrines; the application of ancient history and religious texts to racial problems; pollution and war; and a radical reinterpretation of the Bible in light of Egyptology.

Luckily for us, some sly student captured one of those lectures on tape.

For more of Professor Ra’s spaced out presentation, see the Helsinki interview above, also from 1971. And if you decide you need your own education in “Sun Ra 171,” see the full reading list from his Berkeley course below, courtesy of the blog New Day.

The Egyptian Book of the Dead

Radix

Alexander Hislop: Two Babylons

The Theosophical works of Madame Blavatsky

The Book of Oahspe

Henry Dumas: Ark of Bones

Henry Dumas: Poetry for My People eds. Hale Charfield & Eugene Redmond, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press 1971

Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing, eds. Leroi Jones & Larry Neal, New York: William Morrow 1968

David Livingston: Missionary Travels

Theodore P. Ford: God Wills the Negro

Rutledge: God’s Children

Stylus, vol. 13, no. 1 (Spring 1971), Temple University

John S. Wilson: Jazz. Where It Came From, Where It’s At, United States Information Agency

Yosef A. A. Ben-Jochannan: Black Man of the Nile and His Family, Alkibu Ian Books 1972

Constantin Francois de Chasseboeuf, Comte de Volney: The Ruins, or, Meditation on the Revolutions of Empires, and the Law of Nature, London: Pioneer Press 1921

The Source Book of Man’s Life and Death (Ra’s description; = The King James Bible)

Pjotr Demianovitch Ouspensky: A New Model of the Universe. Principles of the Psychological Method in Its Application to Problems of Science, Religion and Art, New York: Knopf 1956

Frederick Bodmer: The Loom of Language. An Approach to the Mastery of Many Languages, ed. Lancelot Hogben, New York: Norton & Co. 1944

Blackie’s Etymology

Countless other free courses from UC Berkeley can be found in our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

via Dangerous Minds and audio courtesy of Sensitive Skin Magazine

Related Content:

Herbie Hancock Presents the Prestigious Norton Lectures at Harvard University: Watch Online

Sonic Youth Guitarist Thurston Moore Teaches a Poetry Workshop at Naropa University: See His Class Notes (2011)

Space Jazz, a Sonic Sci-Fi Opera by L. Ron Hubbard, Featuring Chick Corea (1983)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness