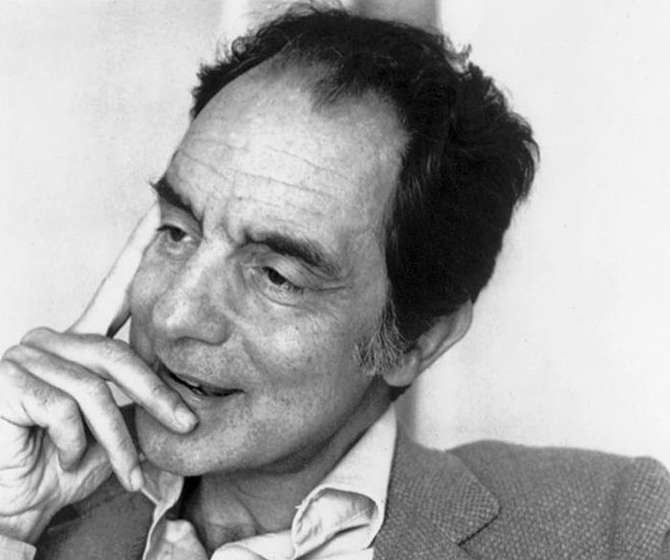

Image by Marie Maye, via Wikimedia Commons

In a previous post, we brought you the voice of Italian fantasist Italo Calvino, reading from his Invisible Cities and Mr. Palomar. Both of those works, as with all of Calvino’s fiction, make oblique references to wide swaths of classical literature, but Calvino is no show-off, dropping in allusions for their own sake, nor is it really necessary to have read as widely as the author to truly appreciate his work, as in the case of certain modernist masters. Instead, Calvino’s fiction tends to cast a spell on readers, inspiring them to seek out far-flung ancient romances and strange folktales, to immerse themselves in other worlds contained within the covers of other books. Not the least bit pedantic, Calvino possesses that rare gift of the best of teachers: the ability to make Literature capital “L”—an intimidating domain for many—become wondrous and approachable all over again, as in our early years when books were magical portals to be entered, not onerous tasks to be checked off a list.

Calvino’s short essay, “Why Read the Classics?” (published in The New York Review of Books in 1986), resounds with this sense of wonder, as well as with the author’s friendly, unpretentious attitude.

He lays out his reasoning in 14 points—slightly abridged below—beginning with the frank admission that all of us feel some sense of shame for the gaps in our reading, and thus often claim to be “re-reading” when in fact we’re reading, for example, Moby Dick, Anna Karenina, or King Lear, for the first time. Calvino states plainly the nature of the case;

The reiterative prefix before the verb “read” may be a small hypocrisy on the part of people ashamed to admit they have not read a famous book. To reassure them, we need only observe that, however vast any person’s basic reading may be, there still remain an enormous number of fundamental works that he has not read.

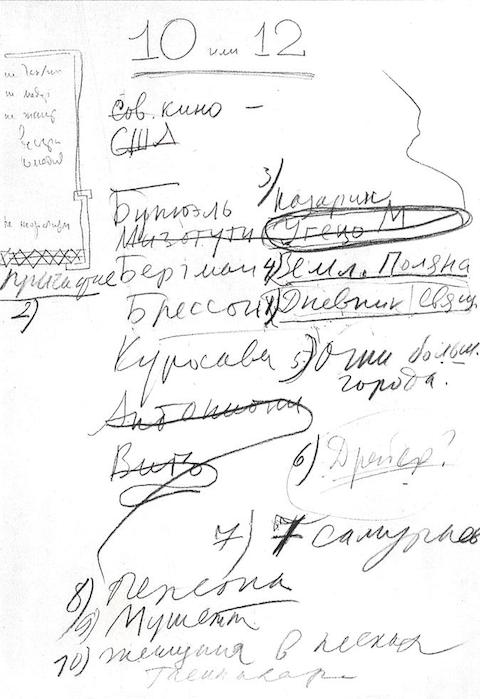

Point one, then, goes on to argue for reading—for the first time—classic works of literature we may have only pretended to in the past. The remainder of Calvino’s case follows logically:

1) ….to read a great book for the first time in one’s maturity is an extraordinary pleasure, different from (though one cannot say greater or lesser than) the pleasure of having read it in one’s youth.

2) We use the word “classics” for those books that are treasured by those who have read and loved them; but they are treasured no less by those who have the luck to read them for the first time in the best conditions to enjoy them.

3) There should therefore be a time in adult life devoted to revisiting the most important books of our youth.

4) Every rereading of a classic is as much a voyage of discovery as the first reading.

5) Every reading of a classic is in fact a rereading.

6) A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.

7) The classics are the books that come down to us bearing upon them the traces of readings previous to ours, and bringing in their wake the traces they themselves have left on the culture or cultures they have passed through.

Calvino introduces his last 7 points with the observation that any formal literary education we receive often does more to obscure our appreciation of classic works than to enhance it. “Schools and universities,” he writes, “ought to help us to understand that no book that talks about a book says more than the book in question, but instead they do their level best to make us think the opposite.”

Part of the reason many people come to literary works with trepidation has as much to do with their perceived difficulty as with the scholarly voice of authority that speaks from on high through “critical biographies, commentaries, and interpretations” as well as “the introduction, critical apparatus, and bibliography.” Though useful tools for scholars, these can serve as means of communicating that certain professional readers will always know more than you do. Calvino recommends leaving such things aside, since they “are used as a smoke screen to hide what the text has to say.” He then concludes:

8) A classic does not necessarily teach us anything we did not know before.

9) The classics are books that we find all the more new, fresh, and unexpected upon reading, the more we thought we knew them from hearing them talked about.

10) We use the word “classic” of a book that takes the form of an equivalent to the universe, on a level with the ancient talismans.

11) Your classic author is the one you cannot feel indifferent to, who helps you to define yourself in relation to him, even in dispute with him.

12) A classic is a book that comes before other classics; but anyone who has read the others first, and then reads this one, instantly recognizes its place in the family tree.

Finally, Calvino adds two points to explain why he thinks we should read old books, when we are so constantly overwhelmed “by the avalanche of current events.” To this question he says:

13) A classic is something that tends to relegate the concerns of the moment to the status of background noise […]

14) A classic is something that persists as a background noise even when the most incompatible momentary concerns are in control of the situation.

In other words, classic literature can have the salutary effect of tempering our high sensitivity to every breaking piece of news and distracting piece of trivia, giving us the ballast of historical perspective. In our current culture, in which we live perpetually plugged into information machines that amplify every signal and every bit of noise, such a remedy seems indispensable.

via The New York Review of Books

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness