Last week saw me in line at one of Los Angeles’ most beloved bookstores, waiting for a signed copy of Haruki Murakami’s new novel Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage upon its midnight release. The considerable hubbub around the book’s entry into English — to say nothing of its original appearance last year in Japanese, when it sold a much-discussed million copies in a single month — demonstrates, 35 years into the author’s career, the world’s unflagging appetite for Murakamiana. Just recently, we featured the artifacts of Murakami’s passion for jazz and a collection of his free short stories online, just as many others have got into the spirit by seeking out various illuminating inspirations of, locations in, and quotations from his work. The author of the blog Randomwire, known only as David, has done all three, and taken photographs to boot, in his grand three-part project of documenting Murakami’s Tokyo: the Tokyo of his beginnings, the Tokyo where he ran the jazz bars in which he began writing, and the Tokyo which has given his stories their otherworldly touch.

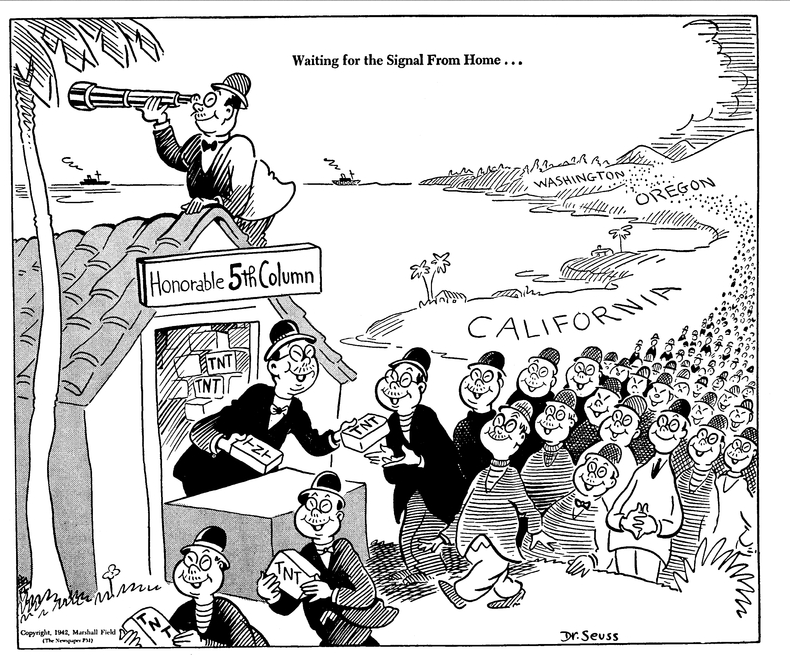

Murakami’s “depictions of the loneliness and isolation of modern Japanese life ingratiated him with the country’s youth who often struggle to assert their individuality in the face of societal notions of conformity,” David writes, noting also that “such comparisons fail to do justice to his unique brand of surreal fantasy and urban realism which seamlessly blends together dream, memory and reality against the backdrop of everyday life in Japan.” Knowing the city of Tokyo as well as he knows the Murakami canon, David works his way from the Denny’s where “Mari, while minding her own business, is interrupted by an old acquaintance Takahashi in After Dark”; to Waseda University, alma mater of both Murakami himself and Norwegian Wood’s protagonist Toru Watanabe; to both locations of Peter Cat, the jazz café and bar Murakami ran with his wife in the 1970s and early 80s; to Meiji Jingu stadium, where Murakami witnessed the home run that somehow convinced him he could write his first novel, Hear the Wind Sing; to DUG, another underground jazz bar visited by students like Toru Watanabe in the 1960s and still open today; to Metropolitan Expressway No. 3, from which 1Q84’s protagonist Aomame climbs down into a parallel reality.

David also drops into spots that, if they don’t count as fully Murakamian, at least count as Murakamiesque, such as an “antique shop-cum-café” opposite the first site of Peter Cat: “Like a surreal plot twist in one of Murakami’s books the scene of me sitting there amongst the mounds of antique junk drinking tea from a porcelain cup was verging on the absurd. More than once I glanced outside the window just to check that the real world hadn’t left me behind.” If you find he missed any patch of Murakami’s Tokyo along the way, let him know; he has, he notes at the end of part three, almost enough for a part four — just as much of Colorless Tsukuru’s follow-up has no doubt already cohered in Murakami’s imagination, that fruitful meeting place of the real and the absurd. Here are the links to the existing sections: Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

Related Content:

Haruki Murakami’s Passion for Jazz: Discover the Novelist’s Jazz Playlist, Jazz Essay & Jazz Bar

In Search of Haruki Murakami, Japan’s Great Postmodernist Novelist

Haruki Murakami Translates The Great Gatsby, the Novel That Influenced Him Most

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.