Click to enlarge

A comparison between the invention of radio and that of the Internet need not be a strained or superfical exercise. Parallels abound. The communication tool that first drew the world together with news, drama, and music took shape in a small but crowded field of amateur enthusiasts, engineers and physicists, military strategists, and competing corporate interests. In 1920, the technology emerged fully into the consumer sector with the first commercial broadcast by Westinghouse’s KDKA station in Pittsburgh on November 2, Election Day. By 1924, the U.S. had 600 commercial stations around the country, and in 1927, the model spread across the Atlantic when the British Broadcasting Corporation (the BBC) succeeded the British Broadcasting Company, formerly an extension of the Post Office.

Unlike the Wild West frontier of U.S. radio, since its 1922 inception the BBC operated under a centralized command structure that, paradoxically, fostered some very egalitarian attitudes to broadcasting—in certain respects. In others, however, the BBC, led by “conscientious founder” Lord John Reith, took on the task of providing its listeners with “elevating and educative” material, particularly avant garde music like the work of Arnold Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School. The BBC, writes David Stubbs in Fear of Music, “were prepared to be quite bold in their broadcasting policy, making a point of including ‘futurist’ or ‘art music,’ as they termed it.” As you might imagine, “listeners proved a little recalcitrant in the face of this highbrow policy.”

In response to the volume of listener complaints, the BBC began a PR campaign in 1927 that sought to train audiences in how to listen to challenging and unfamiliar broadcasts. One statement released by the BBC stresses responsible, “correct,” listening practices: “If there be an art of broadcasting there is equally an art of listening… there can be no excuse for the listener who tunes in to a programme, willy nilly, and complains that he does not care for it.” The next year, the BBC Handbook 1928 included the following castigation of listener antipathy and restlessness.

Every new invention that brings desirable things more easily within our reach thereby to some extent cheapens them… We seem to be entering upon a kind of arm-chair period of civilisation, when everything that goes to make up adventure is dealt with wholesale, and delivered, as it were, to the individual at his own door.

It’s as if Amazon were right around the corner, and, in a certain sense, it was. Like personal computing technology, the wireless revolutionized communications and offered instant access to information, if not yet goods, and not yet on an “on-demand” basis. Unlike Tim Berners-Lee’s World Wide Web, however, British commercial radio strove mightily to control the ethics and aesthetics of its content. The handbook goes on to elaborate its proposed remedy for the potential cheapening of culture it identifies above:

The listener, in other words, should be an epicure and not a glutton; he should choose his broadcast fare with discrimination, and when the time comes give himself deliberately to the enjoyment of it… To sum up, I would urge upon those who use wireless to cultivate the art of listening; to discriminate in what they listen to, and to listen with their mind as well as their ears. In that way they will not only increase their pleasure, but actually contribute their part to the improvement and perfection of an art which is yet in its childhood.

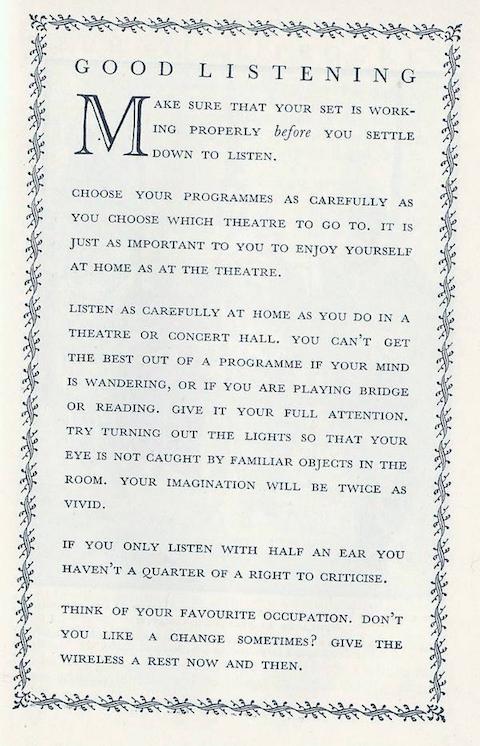

It seems that these lengthy prose prescriptions did not convey the message as efficiently as they might. In 1930, BBC administrators published a handbook that took a much more direct approach, which you can see above. Titled “Good Listening,” the list of instructions, transcribed below, proceeds under the assumption that any dissatisfaction with BBC programming should be blamed solely on impatient, slothful listeners. As BBC program advisor Filson Young wrote that year in a Radio Times article, “Good listeners will produce good programmes more surely and more certainly than anything else… Many of you have not even begun to master the art of listening. The arch-fault of the average listener is that he does not select.”

GOOD LISTENING

Make sure that your set is working properly before you settle down to listen.

Choose your programmes as carefully as you choose which theatre to go to. It is just as important to you to enjoy yourself at home as at the theatre.

Listen as carefully at home as you do in a theatre or concert hall. You can’t get the best out of a programme if your mind is wandering, or if you are playing bridge or reading. Give it your full attention. Try turning out the lights so that your eye is not caught by familiar objects in the room. Your imagination will be twice as vivid.

If you only listen with half an ear you haven’t a quarter of a right to criticise.

Think of your favourite occupation. Don’t you like a change sometimes? Give the wireless a rest now and then.

All maybe more than a little condescending, perhaps, but that last bit of advice now seems eternal.

via WFMU

Related Content:

Orson Welles’ Radio Performances of 10 Shakespeare Plays

Hear Vintage Episodes of Buck Rogers, the Sci-Fi Radio Show That First Aired on This Day in 1932

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness