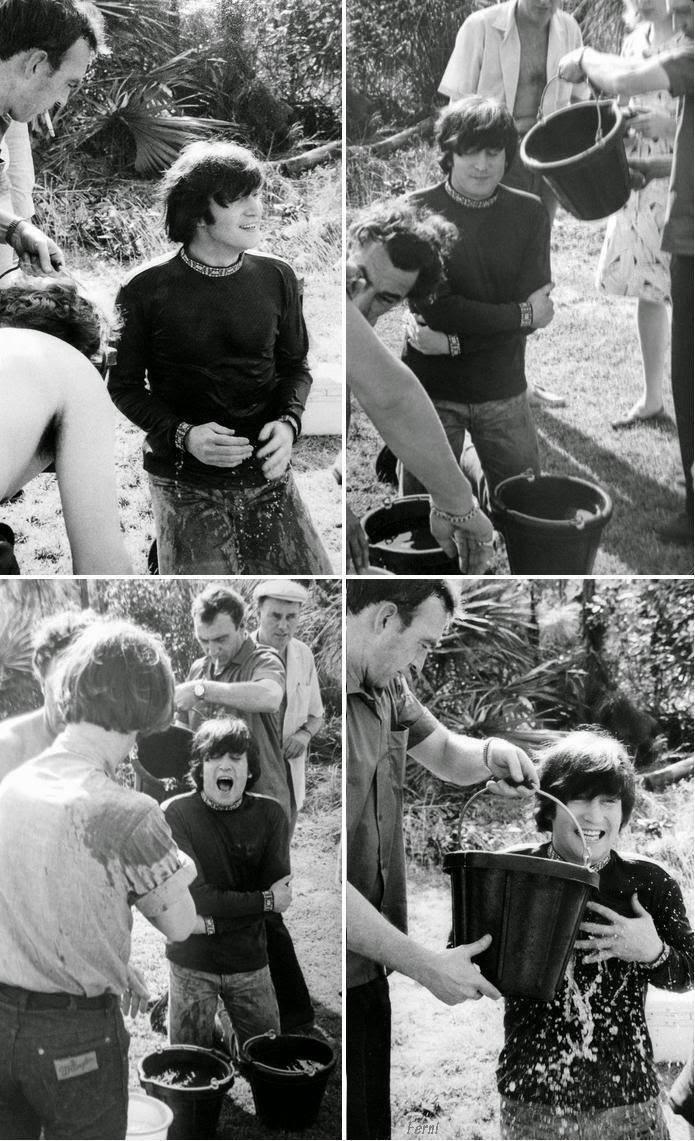

Has any filmmaker, of any era, had more influence on documentaries than Dziga Vertov? We know the early 20th-century Soviet cinema theorist and director of avant-garde non-fiction films has a place high in the documentary pantheon by virtue of his 1929 Man with a Movie Camera alone.

We’ve previously featured that motion picture’s rise to Sight and Sound’s designation of the eighth greatest of all time, and if you didn’t watch it free online then, you can do so above now. Just after that, we featured his unsettling Soviet Toys, the first animated film ever made in that then-nation. But given that the age of Vertov’s work — not that time has diminished its aesthetic relevance or excitement — has brought it into the public domain, why stop there?

Today we offer a roundup of all the Dziga Vertov movies currently viewable free online, a collection that allows you to watch and judge for yourself whether he and his collaborators succeeded in making a dent in what he called “the film drama, the Opium of the people.” Despite the thoroughly low-tech nature of these pictures, even by documentary standards, you may find yourself moved after having watched them — not necessarily by the Soviet causes he sometimes extolled, but by his cinematic rallying cry: “Down with bourgeois fairy-tale scenarios. Long live life as it is!”

- Kino Eye (1924) Vertov’s first documentary not made from found footage journeys, according to a contemporary newspaper, “from the Pioneer camp, through the peasant courtyards, through the fields, through the markets and slums of the town, with an ambulance car to a dying man, from there to workers’ sports grounds, and so on and so forth, peering into all the little corners of social life.”

- Soviet Toys (1924) A “cartoon” that, in the words of our own Jonathan Crow, “displays [Vertov’s] knack for making striking, pungent images,” “yet those who don’t have an intimate knowledge of Soviet policy of the 1920s might find the movie — which is laden with Marxist allegories — really odd.”

- Kino-Pravda #21 (1925) Also known as Lenin Kino-Pravda, “a special, longer-than-usual issue of [newsreel] Kino-Pravda,” as the Harvard Film Archive describes it, “in which Vertov jumps with boldness and ease between newsreel and drawn animation to illustrate Soviet Russia’s way up under Lenin’s leadership, the decline in Lenin’s health, and the year elapsed since his death.”

- A Sixth Part Of The World (1926) A mixture of newsreel and found footage that, according to the Internet Archive, the film depicted “through the travelogue format [ … ] the multitude of Soviet peoples in remote areas of USSR and detailed the entirety of the wealth of the Soviet land,” making “a call for unification in order to build a ‘complete socialist society.’ ”

- Stride, Soviet! (1926) “What began as a commission by the sitting Moscow Soviet for a promotional movie,” says the Harvard Film Archive, “was transformed by Vertov into something else entirely: a film experiment, an emotional film – anything but a picture that would help the Mossovet be reelected.”

- The Eleventh Year (1928) A celebration of “the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution” which, according to the Harvard Film Archive, presents that decade of socialism “in the eyes of a left-wing artist of the twenties” as “a radical social experiment [ … ] required to be presented in a radically experimental way.”

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929) “Made up as it is of ‘bits and pieces’ of cities from Moscow to the Ukraine,” writes Senses of Cinema’s Jonathan Dawson, it “remains a perfect distillation of the sense of a modern city life that looks fresh and true still,” “the strongest reminder that, in spite of the extraordinary pressures on his personal and working life, Vertov was one of the greatest of all the pioneer filmmakers.”

- Three Songs About Lenin (1934) Also known as Three Songs of Lenin and Three Songs Dedicated to Lenin, a delivery of exactly what the title promises — but with a Vertovian stylistic slant.

Related Content:

200 Free Documentaries Online, part of our collection: 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

65 Free Charlie Chaplin Films Online

35 Free Oscar Winning Films Available on the Web

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.