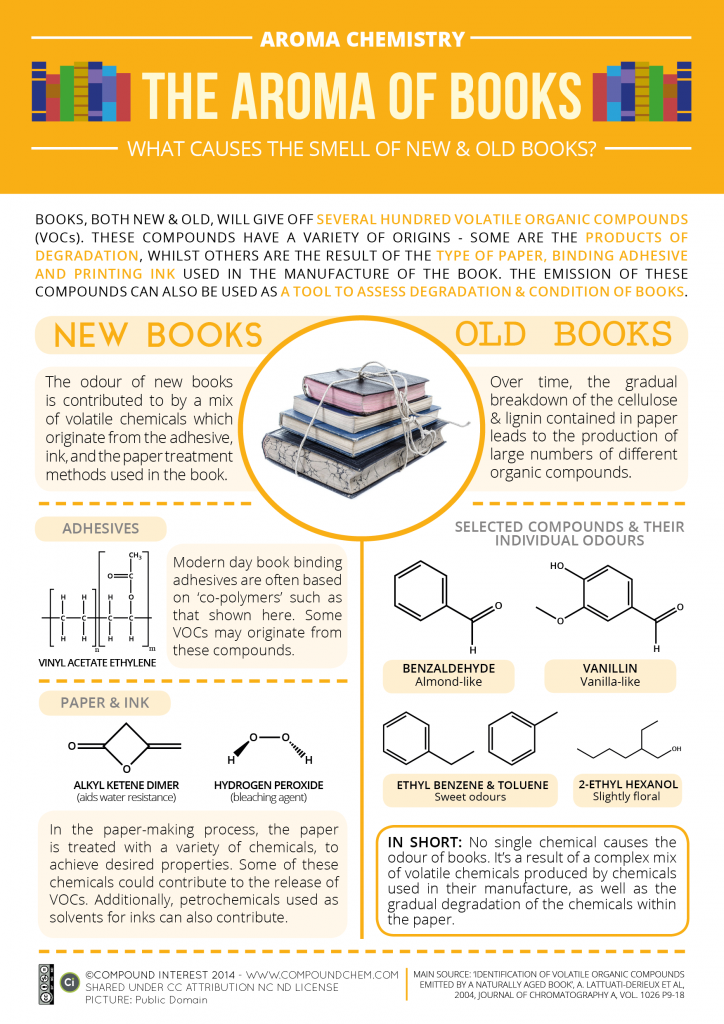

What gives old books that ever-so-distinctive smell? Andy Brunning, a chemistry teacher in the UK, gives us all a quick primer with this infographic posted on his web site, Compound Interest. The visual comes accompanied by this textual explanation. Writes Brunning:

Generally, it is the chemical breakdown of compounds within paper that leads to the production of ‘old book smell’. Paper contains, amongst other chemicals, cellulose, and smaller amounts of lignin – much less in more modern books than in books from more than one hundred years ago. Both of these originate from the trees the paper is made from; finer papers will contain much less lignin than, for example, newsprint. In trees, lignin helps bind cellulose fibres together, keeping the wood stiff; it’s also responsible for old paper’s yellowing with age, as oxidation reactions cause it to break down into acids, which then help break down cellulose.

‘Old book smell’ is derived from this chemical degradation. Modern, high quality papers will undergo chemical processing to remove lignin, but breakdown of cellulose in the paper can still occur (albeit at a much slower rate) due to the presence of acids in the surroundings. These reactions, referred to generally as ‘acid hydrolysis’, produce a wide range of volatile organic compounds, many of which are likely to contribute to the smell of old books. A selected number of compounds have had their contributions pinpointed: benzaldehyde adds an almond-like scent; vanillin adds a vanilla-like scent; ethyl benzene and toluene impart sweet odours; and 2‑ethyl hexanol has a ‘slightly floral’ contribution. Other aldehydes and alcohols produced by these reactions have low odour thresholds and also contribute.

The Aroma of Books infographic can be viewed in a larger format here. And because it has been released under a Creative Commons license, it can be downloaded for free. For another explanation of this phenomenon — this one in video — see this previous post in our archive: The Birth and Decline of a Book: Two Videos for Bibliophiles

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

A Secret Bookstore in a New York City Apartment: The Last of a Dying Breed

Old Books Bound in Human Skin Found in Harvard Libraries (and Elsewhere in Boston)

Spike Jonze Presents a Stop Motion Film for Book Lovers

Wearable Books: In Medieval Times, They Took Old Manuscripts & Turned Them into Clothes