We’ve seen how modern dance can explain key concepts in statistics (e.g. correlation and sampling error). So why couldn’t dance also illustrate the conclusions of a plant biology doctoral dissertation?

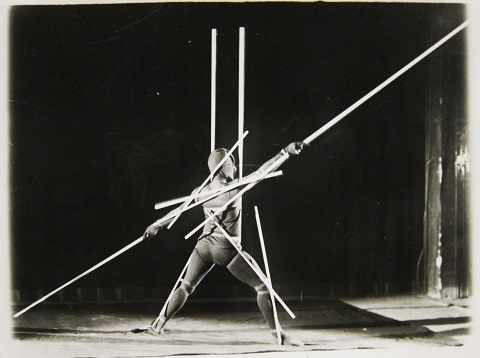

Uma Nagendra, a graduate student at the University of Georgia, has just won the 2014 edition of the “Dance Your Ph.D.” contest. Sponsored by Science and HighWire Press, the contest asks grad students to “explain their Ph.D. research in the most jargon-free medium of all: dance.” (More criteria can be found over at the contest’s tips & tricks page.) According to Science magazine, Nagendra likes to spend “a good deal of her [free] time hanging upside down from a trapeze doing circus aerials.” It’s a creative outlet for her. And it offers a good way, it turns out, to visualize the conclusions of her dissertation exploring “Plant-soil feedbacks after severe tornado damage.”

The “Dance Your Ph.D.” contest allows each contestant to submit a video with a short piece of descriptive text. Here is what Nagendra wrote:

Many of the patterns we see in forests around the world are caused by the relationships that plants have with organisms in the soil. Some very diverse forests can only support as many different tree species as they do because soil-borne diseases prevent any one species from taking over. But what happens when a tornado comes along? Do the plants and soil organisms maintain this diversity-promoting relationship?

My PhD research focuses on how several different species of tree seedlings in the southern Appalachian mountains interact with soil organisms—and how tornadoes might mix things up. I study many different species. As an example, we can look at white pine (Pinus strobus), and the many pathogens that attack the roots of its seedlings.

The dance begins in an undisturbed forest. Because trees live for so long in one place, a mature pine tree accumulates a unique group of fungi around its roots—including pathogens that cause diseases in tree seedlings (in this case, Pythium and Rhizoctonia). White pine seedlings that are very close to a mature tree are more likely to be attacked by these pathogens—causing stunted growth, or even death. The farther away a seedling is from a mature tree, the less likely it is to get infected. These distant seedlings are more likely to survive to maturity. A pattern emerges where the mature pine trees are spaced far apart—leaving room for seedlings of other species to grow, and creating a diverse forest.

In the middle of the dance, we witness the tornado—and how it changes the forest environment. The mature pine tree dies, and the forest floor is no longer shaded. The soil becomes hotter and drier. Without the living mature tree as a host, specialist pathogens are less active, and many die. Because of this, I am predicting that plant-soil relationships in recently tornado-damaged areas may be much weaker. In the last part of the dance, seedlings close to the (killed) mature tree are no longer at greater risk for disease; they grow and survive the same as their more distant siblings. The changing plant-soil relationships after disturbances might be one piece in the puzzle of how diverse ecosystems change over time.

via Explore

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Google Plus and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox.

Related Content:

Statistics Explained Through Modern Dance: A New Way of Teaching a Tough Subject

The Illustrated Guide to a Ph.D.

Serial Entrepreneur Damon Horowitz Says “Quit Your Tech Job and Get a Ph.D. in the Humanities”