Like all great writers, Leo Tolstoy has inspired a great many visual adaptations of his work, of varying degrees of quality. Just this past month, the Volgograd Fine Arts Museum in Russia held an exhibition of “92 graphic works from the collection of the Yasnaya Polyana Estate-Museum,” the author’s country estate and birthplace. Each work of art “recreates immortal images of the characters, reconstructs the historic epoch, and reflects the dynamics” of his masterpieces Anna Karenina and War and Peace, as well as his short stories for children.

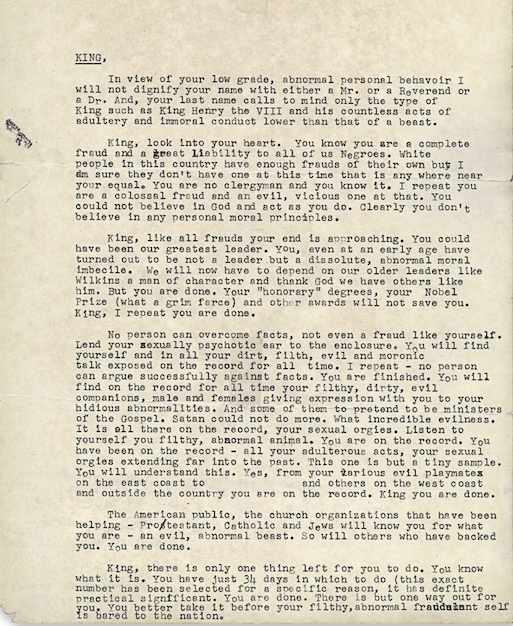

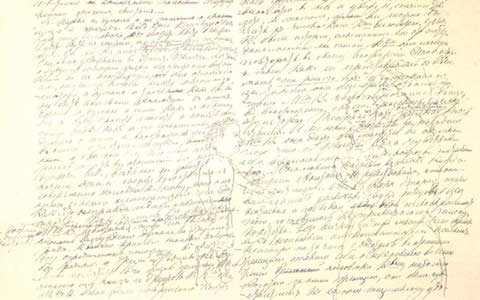

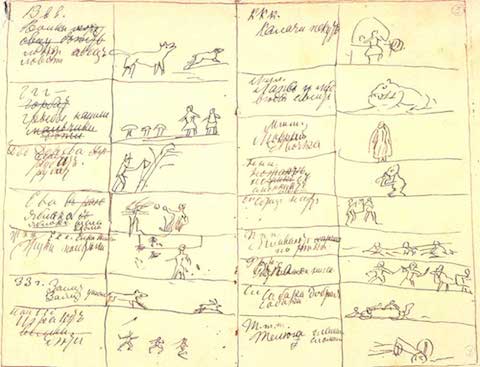

Travel to Moscow, however, to the Leo Tolstoy State Museum, and you’ll find Tolstoy’s own visual art, which he sketched both on the very manuscript pages of those novels and stories and in the notebooks that inspired them. At the top of the post, see a manuscript page of War and Peace with the figures of a boy and a well-dressed woman drawn very faintly into the text. Directly above, see a sketch for his ABC book, a primer he created for his peasant schools at Yasnaya Polyana.

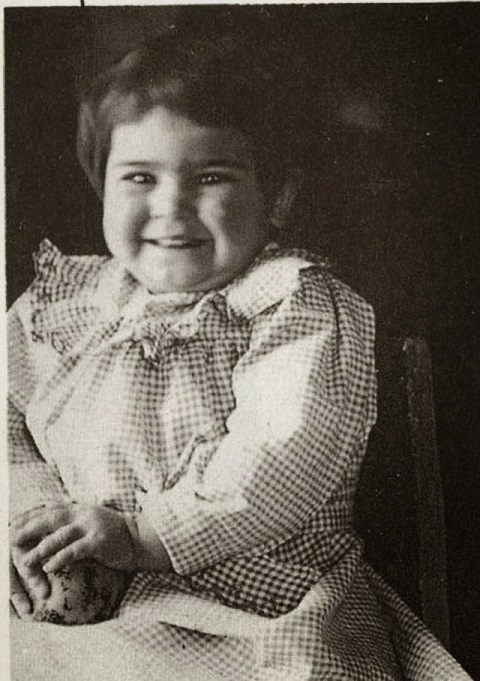

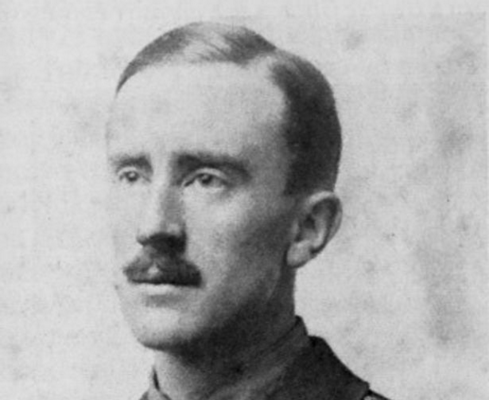

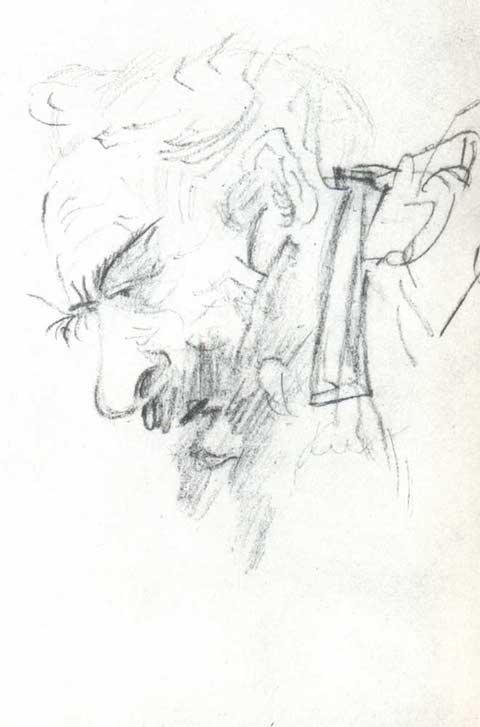

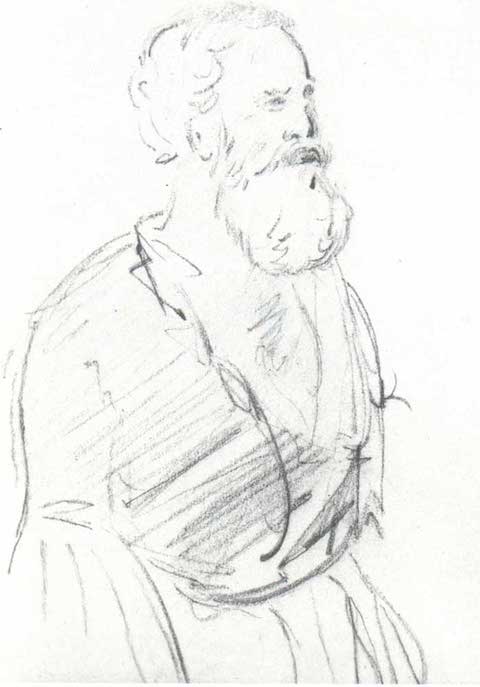

Tolstoy didn’t only illustrate his own work; he also made some sketches of his contemporary Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days—see one above—which he read in French with his children. These few drawings may seem like little more than doodles, but Tolstoy in fact had a very fine hand, as you can see in the two sketches below from notebooks he kept during his time in the Caucusus. It was then, while serving in the army, that Tolstoy began writing, and the notebooks he kept would eventually inspire his 1863 novel, The Cossacks.

These drawings are so well rendered they make me think Tolstoy could have become a visual artist as well as a great writer. But perhaps the exacting novelist was too harsh a critic to allow himself to pursue that course. Over forty years after making these drawings, Tolstoy published his thoughts on art in essay called What is Art?. In it, the great Russian writer creates what Gary R. Jahn in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism admits are some “unreasonably narrow, exclusive” criteria for defining art.

Tolstoy also propounds something akin to a meme theory, which he calls a quality of “infectiousness.” Art, he writes, is “a human activity consisting in this, that one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that other people are infected by these feelings and also experience them.” At the crucially formative period when these drawings were made, Tolstoy obviously decided he could best “infect” others through writing. That same year, he published the first part of his autobiographical trilogy, Childhood, under a pseudonym, followed quickly by Boyhood. By the time he retired from the army in 1856 and left the Caucusus for St. Petersburg, he was already a literary celebrity. See more of Tolstoy’s drawings from his Caucusus notebooks here.

Related Content:

Leo Tolstoy Creates a List of the 50+ Books That Influenced Him Most (1891)

Rare Recording: Leo Tolstoy Reads From His Last Major Work in Four Languages, 1909

Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925

The Drawings of Jean-Paul Sartre

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness