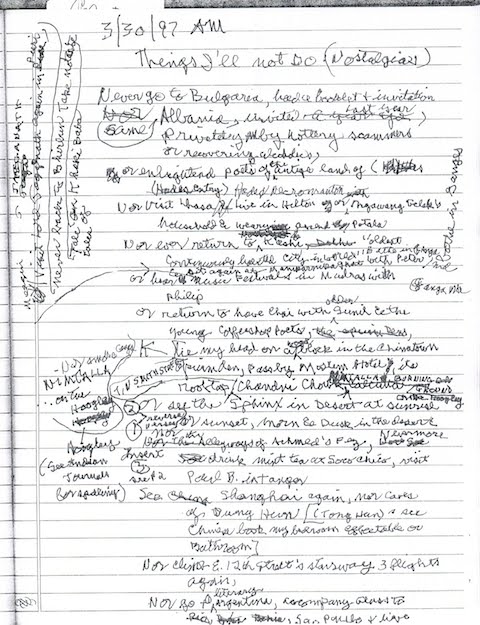

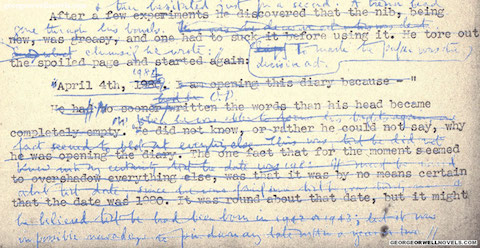

Allen Ginsberg died on April 5, 1997. Less than a week before, after the long terminally ill poet had made parting phone calls to nearly everyone in his address book, he wrote the poem above, “Things I’ll Not Do (Nostalgias).” He once called all his work extended biography, and we might call this particular work a piece of biography extended into speculation, comprising all the places (Tibet, Morocco, Los Angeles), people (composer Philip Glass, noted Tangier expat Paul Bowles, his own relatives), and things (attending concerts, teaching students, smoking various substances) he knew he would never experience again, or indeed for the first time — items left over, in short, from what we might now call Ginsberg’s bucket list. The transcript runs as follows:

Never go to Bulgaria, had a booklet & invitation

Same Albania, invited last year, privately by Lottery scammers or

recovering alcoholics,

Or enlightened poets of the antique land of Hades Gates

Nor visit Lhasa live in Hilton or Ngawang Gelek’s household & weary

ascend Potala

Nor ever return to Kashi “oldest continuously habited city in the world”

bathe in Ganges & sit again at Manikarnika ghat with Peter,

visit Lord Jagganath again in Puri, never back to Bibhum take

notes tales of Khaki B Baba

Or hear music festivals in Madras with Philip

Or enter to have Chai with older Sunil & Young coffeeshop poets,

Tie my head on a block in the Chinatown opium den, pass by Moslem

Hotel, its rooftop Tinsmith Street Choudui Chowh Nimtallah

Burning ground nor smoke ganja on the Hooghly

Nor the alleyways of Achmed’s Fez, nevermore drink mint tea at Soco

Chico, visit Paul B. in Tangiers

Or see the Sphinx in Desert at Sunrise or sunset, morn & dusk in the

desert

Ancient sollapsed Beirut, sad bombed Babylon & Ur of old, Syria’s

grim mysteries all Araby & Saudi Deserts, Yemen’s sprightly

folk,

Old opium tribal Afghanistan, Tibet — Templed Beluchistan

See Shangha again, nor cares of Dunhuang

Nor climb E. 12th Street’s stairway 3 flights again,

Nor go to literary Argentina, accompany Glass to Sao Paolo & live a

month in a flat Rio’s beaches and favella boys, Bahia’s great

Carnival

Nor more daydream of Bali, too far Adelaide’s festival to get new scent

sticks

Not see the new slums of Jakarta, mysterious Borneo forests & painted

men and women

Nor mor Sunset Boulevard, Melrose Avenue, Oz on Ocean Way

Old cousin Danny Leegant, memories of Aunt Edith in Santa Monica

No mor sweet summers with lovers, teaching Blake at naropa,

Mind Writing Slogans, new modern American Poetics, Williams

Kerouac Reznikoff Rakosi Corso Creely Orlovsky

Any visits to B’nai Israel graves of Buda, Aunt Rose, Harry Meltzer and

Aunt Clara, Father Louis

Not myself except in an urn of ashesMarch 30, 1997, A.M.

Allen Ginsberg

As much of a final statement as it sounds like, “Things I’ll Not Do (Nostalgias)” remains, in a way, a work in progress, given the manuscript’s semi-decipherable hand. “Although many of his poems’ first drafts looked like this,” say the caretakers of AllenGinsberg.org, “if anything was unclear, we could just ask. That, obviously, wasn’t an option after April 5 that year.” Ten of Ginsberg’s associates passed the paper around, Google- and Wikipedialessly trying to piece together all of his characteristically far-flung references. The Caves of Dunhuang “went incorrectly transcribed for the first edition as ‘cares of Dunhuang’, since none of us were aware these were caves,” and “when we got to the ‘antique lands of Hades Necromanteion,” we couldn’t find a single reference to it anywhere, and in the end simply stated ‘Hades Gates.’ That’s how it’s published today — still. Till the next edition that is.”

Related Content:

The Last (Faxed) Poem of Charles Bukowski

Hear the Very First Recording of Allen Ginsberg Reading His Epic Poem “Howl” (1956)

James Franco Reads a Dreamily Animated Version of Allen Ginsberg’s Epic Poem ‘Howl’

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.