When a country is in the headlines almost every day, it can be easy to forget that today’s news isn’t the whole story. Iran’s modern story features its long, bloody war with Iraq, contested presidential election results, and protests that became part of the Arab Spring.

But Iran is also known by its ancient name of Persia and is one of the world’s oldest civilizations.

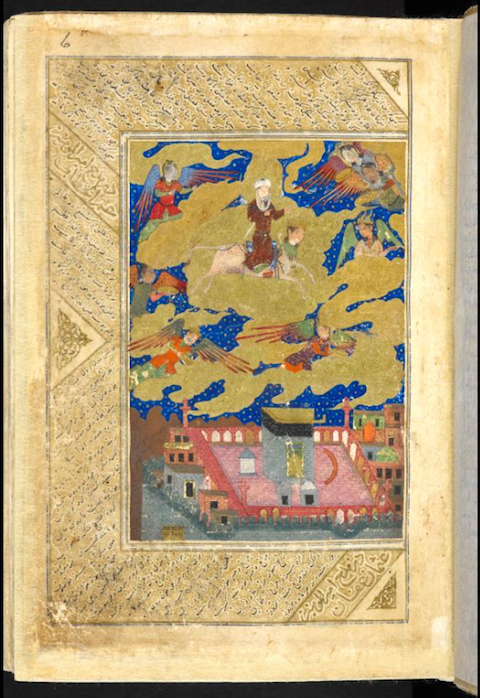

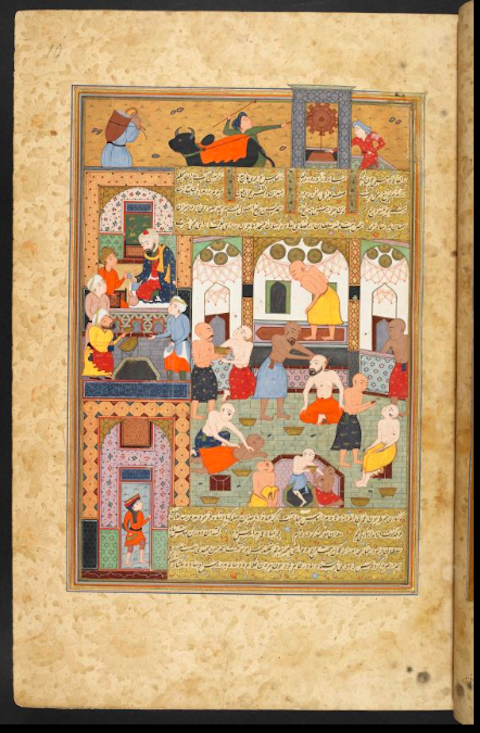

In the 12th century, all of Mesopotamia blossomed. The Islamic Golden Age was a time of thriving science, scholarship and art, including bright and vivid Persian miniatures—small paintings on paper created to be collected into books.

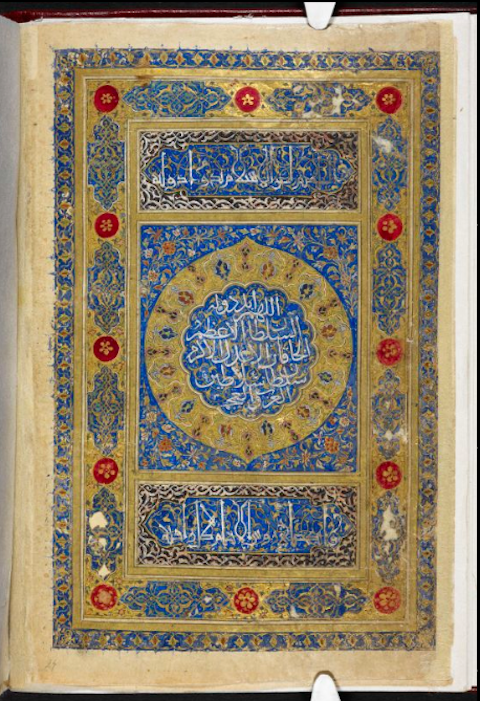

Thousands of these miniatures—known for their bright and pure coloring—are now included in a new digital archive developed by the British Library. The paintings, often accompanied by beautiful Persian texts, are meticulously preserved, making available delicate treasures on par with, if not more beautiful than other illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells.

Because the miniatures were meant to be enjoyed in private, in books, artists could be freer with their subjects than with public wall paintings. Most miniatures included human figures, including depictions of the prophet Muhammed that showed his face, and “illuminated” ornamental borders.

The joy of the archive, which includes works from the British Museum and India Office Library, is how close we can get to the work. Zoom in as close as you like to examine the delicate flowers and script (click the screenshots to zoom into each painting). With this technology, it’s possible to see things that the naked eye would miss.

A separate archive houses rare Persian texts, including this pocket encyclopedia. The greatest beneficiaries are scholars, who can pore over beautiful, fragile documents and artwork from wherever they work, without damaging the old materials.

via The Paris Review

Related Content:

Free: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Offer 474 Free Art Books Online

Download Over 250 Free Art Books From the Getty Museum

Kate Rix writes about digital media and education. Visit her on Twitter.