Click to enlarge

Today marks the 215th anniversary of pioneering English naturalist Charles Darwin’s birth — a suitable occasion, perhaps, to finally take that copy of On the Origin of Species down off your shelf (or from our collection of Free eBooks). Though Darwin’s best-known publication lays out his observations on evolution by natural selection, culminating in the theory often and unhesitatingly called the most important in biology, the book remains more respected than read. Still, any scientist’s legacy, even that of one with a name so widely known as Darwin’s, comes down to what they understood, and thus what they allowed the rest of humanity to understand, not what they wrote. But you still have to wonder: what did Darwin read?

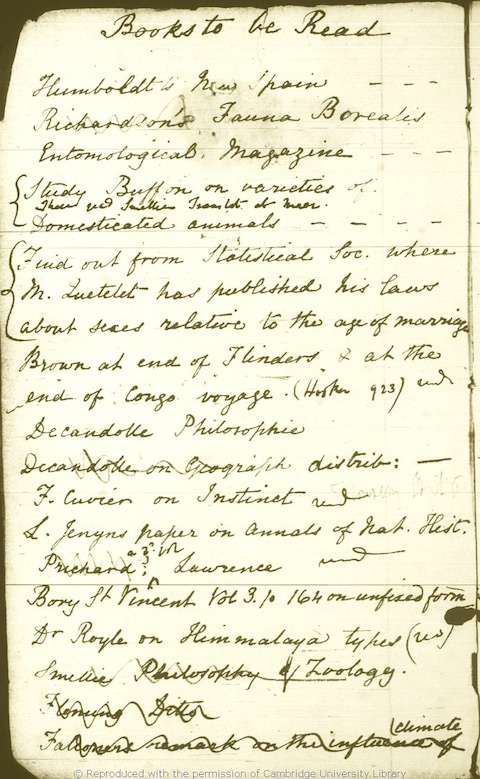

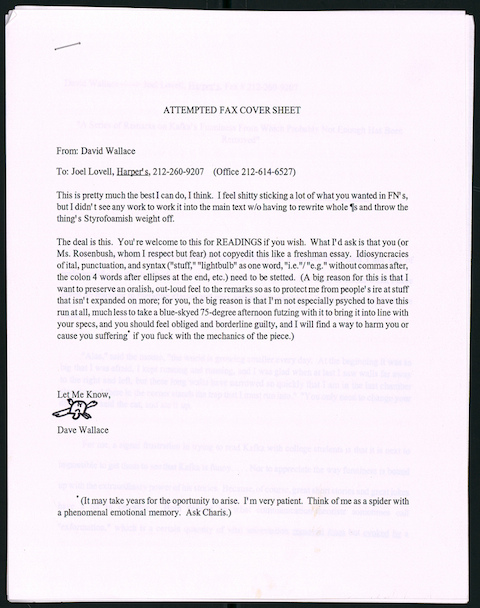

We have two answers to that question, the first of which comes in the form of Darwin’s 1838 “to read” list above, which runs as follows:

Humboldt’s New Spain — — —

Fauna Borealis

Richardson’s

Entomological Magazine — — —

Study Buffon on varieties of Domesticated animals — — — —

Find out from Statistical Soc. where M. Quetelet has published his laws about sexes relative to the age of marriage

Brown at end of Flinders & at the end of Congo voyage (Hooker 923) read

Decandolle Philosophie

Decandolle on Geograph distrib:—

F. Cuvier on Instinct read

L. Jenyns paper in Annals of Nat. Hist.

Prichard; a 3d vol Lawrence read

Bory St Vincent Vol 3. p 164 on unfixed form: Dr Royle on Himmalaya types (read)

Smellie Philosophy of Zoology.

Fleming Ditto

Falconers remark on the influence of climate

You can find more on the list’s context at Endpaper, whose post describes it as found in Darwin’s “series of notebooks for theoretical work now known as Notebooks A, B, C, D, etc.,” specifically Notebook C. (The famous Tree of Life sketch, they add, came from Notebook B.) For our second answer to the question of which books equipped the celebrated biologist’s mind, we offer the books that furnished his home: back in 2011, we featured Cambridge University’s Biodiversity Heritage Library and its project to digitize and make freely available 330 texts from Darwin’s library. All come annotated by the man himself, so you can learn not just from what he read, but about how he read. The next, much more difficult step, then presents itself: to think how he thought.

Related Content:

Watch Darwin, a 1993 Film by Peter Greenaway

Read the Original Letters Where Charles Darwin Worked Out His Theory of Evolution

The Genius of Charles Darwin Revealed in Three-Part Series by Richard Dawkins

Darwin’s Personal Library Goes Digital: 330 Books Online

Darwin’s Legacy, a Stanford course in our collection of 750 Free Online Courses

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.