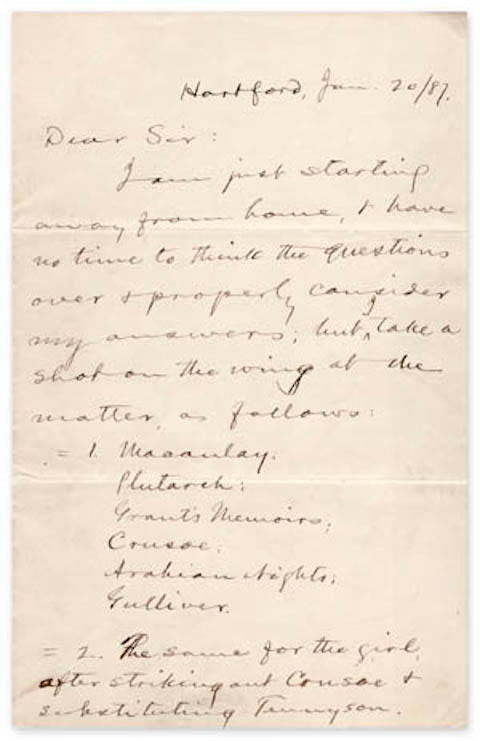

“If my Valentine you won’t be,

I’ll hang myself on your Christmas tree.”

― Ernest Hemingway, 88 Poems

Strangely, that’s one activity that didn’t make Men’s Health reporter Markham Heid’s list of 10 Valentine’s Day distractions for the newly dumped. Yoga classes and Singles Fun Runs do sound healthful, but many will find suggestion number 10—wallowing in it—the most viable option.

Musical experimentalists Collective Cadenza’s Valentine’s Day Special “A History of Men Moving On” is to wallowing as speed dating is to courtship.

It’s a five minute medley of male romantic pain that takes us all the way from Roy Orbison’s 1960 “Only the Lonely” to CeeLo Green’s pointed “Fuck You.”

Vocalist Forest Van Dyke exhibits considerable dexterity, navigating these stylistic switchbacks. A shame he was directed to deliver so much of this choice material to a framed photo, awkwardly positioned on an upstage music stand. I know that the room was crowded, but I would’ve liked to see his feet, too. A man who can dance is something to see.

Kudos to musical director Michael Thurber for making explicit the similarities between Gotye’s “Somebody That I Used To Know” and Usher’s “Papers” (as covered by a goat). As with Hemingway’s couplet, the latter failed to make the round up. Does the heartbreak ever cease?

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Related Content:

A Lover’s Spat Set to the Lyrics of 17 Beatles Songs

Tom Waits Shows Us How Not to Get a Date on Valentine’s Day

Barry White’s Philosophy of Music and Making Love, Animated

Ayun Halliday is stapling up a new issue of her zine, The East Village Inky. Follow her @AyunHalliday