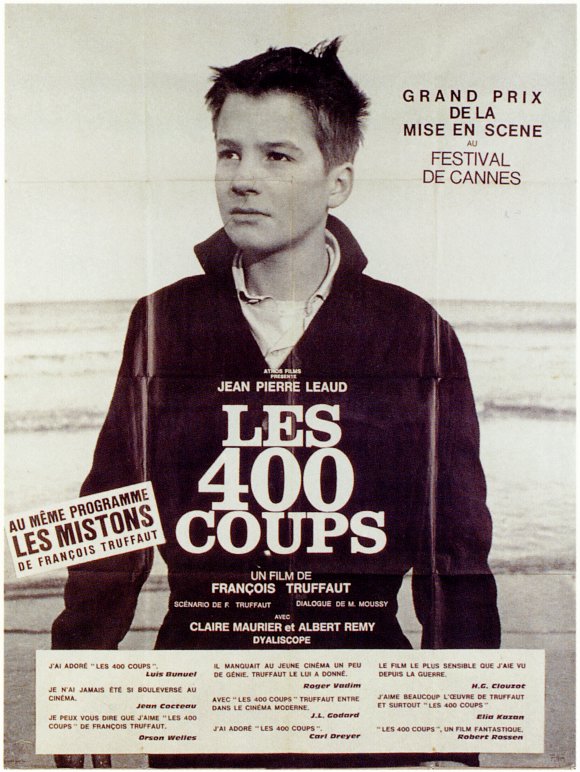

“Cinema saved my life,” confided François Truffaut. He certainly returned the favor, breathing new life into a French cinema that was gasping for air by the late 50s, plagued as it was by academism and Big Studios’ formulaic scripts. From his breakthrough first feature 400 Blows in 1959–to this day one of the best movies on childhood ever made–to his untimely death in 1984, Truffaut wrote and directed more than twenty-one movies, including such cinematic landmarks as Jules and Jim, The Story of Adele H., The Last Metro and the tender, bitter-sweet Antoine Doinel series, a semi-autobiographical account of his own life and loves. What is more, along with a wild bunch of young film critics turned directors—his New Wave friends Godard, Chabrol, Rivette and Resnais—Truffaut revolutionized the way we think, make and watch films today. (We will see how in my upcoming Stanford Continuing Studies course, When the French Reinvented Cinema: The New Wave Studies, which starts on March 31. If you live in the San Francisco Bay Area, please join us.)

Almost as interesting as Truffaut’s rich legacy is the narrative that led to it: How Truffaut became Truffaut against all odds. And how his unlikely background as an illegitimate child, petty thief, runaway teen and deserter built the foundations for the ruthless film critic and gifted director he would become.

Les 400 Coups, we see a fictionalized version of the defining moments in the young François’ life through the character of Antoine Doinel: the discovery that he was born from an unknown father, the contentious relationship with a mother who considered him a burden and condescended to take him with her only when he was ten, the friendship with classmate Robert Lachenay and the endless wanderings in the streets of Paris that ensued. The film offers a glimpse of the dearth of emotional as well as material comfort at home and how Antoine makes do with it, mostly by pinching money, time and dreams of love elsewhere: Antoine “borrows” bills and objects (Truffaut, too, took and sold a typewriter from his dad’s office), steals moments of freedom in the streets, and loves vicariously through the movie theaters (in the trailer above, Antoine and his friend catch a showing of Ingmar Bergman’s Monika).

If anything, the real Truffaut did far worse than his cinematic alter ego. Like Antoine, the young François skipped schools, stole, told lies, ran away and went to the movies on the sly. He ran up debts so high—mostly to pay for his first ciné-club endeavors—that he was sent to a juvenile detention center by his father. Later, having enlisted in the Army, Truffaut deserted upon realizing he would be sent to Indochina to fight: prison was again his lot. In his cell, he received letters from the great prisoner of French letters, Jean Genêt: it was only fitting that the young Truffaut would become friends with the author of The Journal of a Thief.

But had he been a better kid, Truffaut might never have been such a great director. His so-called moral shortcomings foreshadow what would make his genius: an impulsive need to bend the rules, a talent for working at the margins and invent new spaces to free himself from formal limitations, and a fundamental urge to be true to his own vision, at the risk of infuriating the older generation. His years of truancy roaming the streets and movie theaters of Paris and his repeated experience of prison led him naturally to revolt against the confinement of the studio sets where movies were at the time entirely made. Instead, he took his camera out of the studios and into the streets. On location shooting, natural light, improvised dialogues, vivacious tracking shots of the pulse of the city — all traits that made the New Wave look refreshingly new and modern — befitted the temperament of an independent young man who had already spent too many days behind bars.

Having gotten in so much trouble for lack of money, Truffaut also ensured that financial independence would be the cornerstone of his film-making: one of the smartest moves he made as a young director was to found his own production company, the Films du Carrosse. Money meant freedom, this much he had long learnt.

But it is Truffaut’s innate sense of fiction and story telling that his younger years reveal most. Like the fictional Antoine in this clip, Truffaut seemed to have displayed a disarming mix of innocence and deception, or rather an unabashed admission that he had to invent other rules to get by and succeed, and a precocious realization that telling stories would get him further than telling the truth. “Des fois je leur dirais des choses qui seraient la vérité ils me croiraient pas alors je préfère dire des mensonges” tells Antoine in his grammatically incorrect French to the psychologist—“Sometimes if I were to tell things that would be true they would not believe me so I prefer to tell lies.” Each survival trick, each prank implied new lies to forge, and a keen understanding of his public was paramount for their success: contrary to Godard and his avant-garde deconstruction of narrative lines and meaning, Truffaut always wanted to tell good, believable stories: one could say he practiced his narrative skill by telling the tales his first audience (mother, father, teachers) wanted to hear.

One of the most memorable lines of 400 Blows is a lie so outrageous that it has to be believed. Asked by his teacher why he was not able to turn in the punitive homework he was assigned, Antoine blurts out: “It was my mother, sir.” – “Your mother, your mother… What about her?” –“She’s dead.” The teacher quickly apologizes. But this blatant lie tells another kind of truth, an emotional one that the audience is painfully aware of: Antoine’s, or should we say Truffaut’s mother is indeed “dead” to him, unable to show motherly affection. The mother’s death is less a lie than a metaphor, the subjective point of view of the child. Truffaut the director is able to allude to this deeper mourning but also to save the mother from her deadly coldness by the sheer magic of fiction. Antoine’s votive candle has almost burnt down the house, his parents are fighting, his dad threatens to send him to military school, when suddenly the mother suggests they all go… to the movies. Unexpectedly, magically, they emerge from the theater cheerful and united, in a scene of family happiness that can exist only in films. For a moment, cinema saved them all.

To learn more about Truffaut’s life and work, we recommend Stanford Continuing Studies Spring course “The French New Wave.” Laura Truffaut, François Truffaut’s daughter, will come and speak about her father’s work.

Cécile Alduy is Associate Professor of French at Stanford University. She writes regularly for The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker.