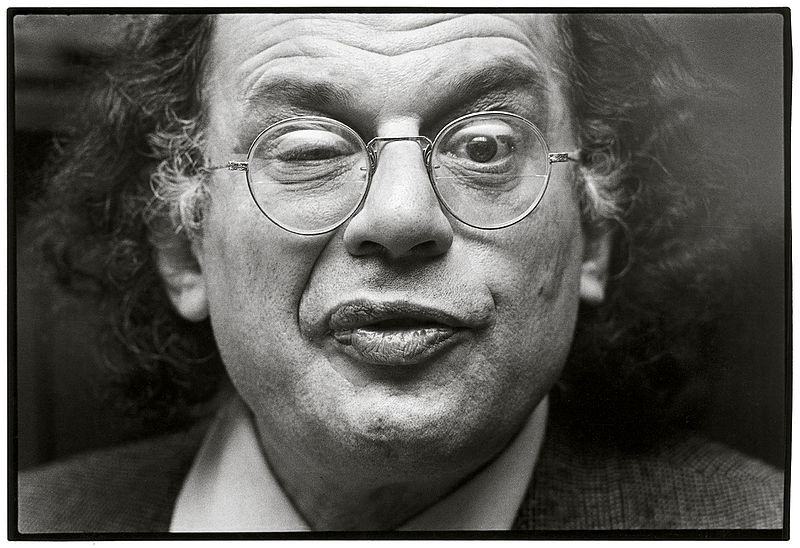

Dizzy Gillespie was one of the best jazz trumpet players of all time. His virtuosic playing, along with his tricked out trumpet and his freakishly elastic cheeks, turned him into a musical icon of the 20th century. But did you know that he lent his voice to an Oscar-winning movie?

The Hole (1962), which you can see above, is an experimental animated short about two construction workers engaged in an increasingly intense conversation about free will and the possibility of an accidental nuclear war. Gillespie improvised the dialogue opposite actor George Matthews, a giant of a man who was most famous for playing movie thugs. The style of the animation is loose, blotchy and rough – in other words, about as un-Disney as can be.

And that was by design. John Hubley, who directed the movie along with his wife Faith Hubley, got his start in animation by working on some of Disney’s most famous early films including Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, Bambi and Fantasia, but he found that his artistic ambitions lay beyond Uncle Walt’s vision. After the war, he helped found the United Productions of America and even created its most successful character – Mr. Magoo — only to be forced out of the company during the Red Scare.

After marrying Faith in 1955, Hubley founded Storyboard Studios to make visually adventurous, socially minded animated movies. (Fun fact: John and Faith Hubley’s daughter Georgia grew up to be the drummer for the indie band Yo La Tengo.) The Hole (1962) proved to be very successful for the studio; it won an Academy Award for Best Animated Short and in 2013, it was selected for the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Gillespie and the Hubleys continued to collaborate in two other movies The Hat, which co starred Dudley Moore, and the supremely groovy Voyage to Next (1974). In that latter film, above, Dizzy and Maureen Stapleton play Father Time and Mother Nature respectively. They watch in wonder, concern and eventually alarm as humanity evolves from communal villagers to greedy nationalists on the brink self-annihilation.

You can find both films listed in the Animation section of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

via Dangerous Minds and NPR

Related Content:

Dizzy Gillespie Runs for US President, 1964. Promises to Make Miles Davis Head of the CIA

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.