A completely unsurprising thing has happened during the first season of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos reboot. Creationists vocally complained that the show does not give their point of view an equal hearing. Tyson responded, saying “you don’t talk about the spherical earth with NASA and then say let’s give equal time to the flat-earthers.” The analogy is more amusing than effective, since roughly fifty percent of Americans are Creationists, while perhaps 49.9 percent fewer believe the earth is flat. But the point stands. If scientific theories were arrived at by popular vote, the “equal time” argument might make some sense. Of course that’s not how science works. Is this bias? As Tyson put it in one of his well-crafted tweets, “you are not biased any time you ever speak the truth.”

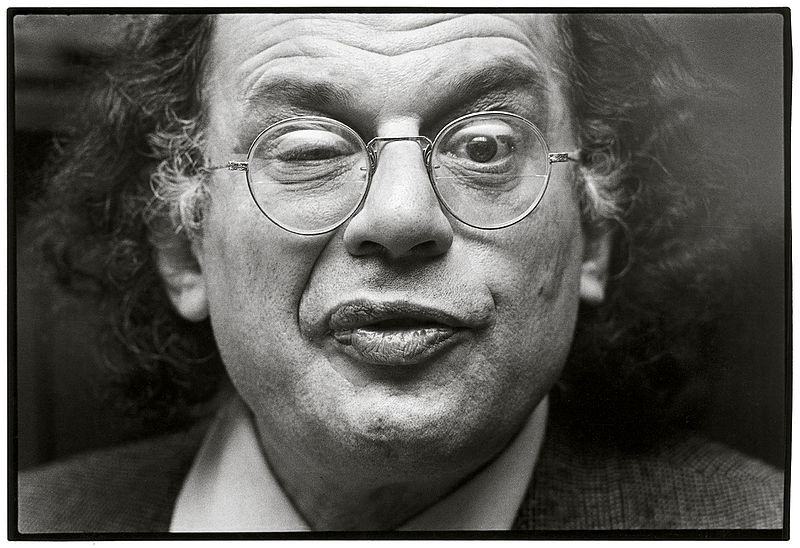

“But what is truth?” asks a certain kind of skeptic. That, suggests the late Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman above, depends upon your method. If you’re doing science, you may find answers, but not necessarily the ones you want:

If you expected science to give all the answers to the wonderful questions about what we are, where we’re going, what the meaning of the universe is and so on, then I think you can easily become disillusioned and look for some mystic answer.

Going to the sciences, says Feynman, to “get an answer to some deep philosophical question,” means “you may be wrong. It may be that you can’t get an answer to that question by finding out more about the character of nature.” Science does not begin with answers, but with doubt: “Is science true? No, no we don’t know what’s true, we’re trying to find out.” Feynman’s scientific attitude is profoundly agnostic; he’d rather “live with doubt than have answers that might be wrong.”

Feynman couches his comments in personal terms, admitting there are scientists who have religious faith, or as he puts it “mystic answers,” and that he “doesn’t understand that.” He declines to say anything more. While similarly agnostic, Neil deGrasse Tyson states his opinions a bit more forcefully on scientists who are believers, saying that around one third of “fully-functioning” “Western/American scientists claim that there is a god to whom they pray.” Yet unlike the claims of Answers in Genesis and other Creationist outfits, “There is no example of someone reading their scripture and saying, ‘I have a prediction about the world that no one knows yet, because this gave me insight. Let’s go test that prediction,’ and have the prediction be correct.”

Both Feynman and Tyson seem to agree that the scientific and Creationist methods for discovering “truth,” whatever that may be, are basically incompatible. Says Feynman: “There are very remarkable mysteries… but those are mysteries I want to investigate without knowing the answers to them.” For that reason, says Feynman, he “can’t believe the special stories that have been made up about our relationship to the universe.” His wording recalls the phrase Answers in Genesis uses to characterize human origins: “special creation,” the description of a method that places meaning and value before evidence, and doggedly assumes to know the truth about what it sets out to investigate in ignorance.

Confronted with the Creationists of today, Feynman would likely lump them in with what he called in a 1974 Caltech commencement speech “Cargo Cult Science,” or “science that isn’t science” but that intimidates “ordinary people with commonsense ideas.” That lecture appears in a collection of Feynman’s speeches, lectures, interviews and articles called The Pleasure of Finding Things Out, which also happens to be the title of the program from which the clip at the top comes.

Produced by the BBC in 1981, the hour-long interview was taped for a show called Horizon which, like Cosmos, showcases scientists sharing the joys of discovery with a lay audience. Like Neil deGrasse Tyson, and Carl Sagan before him, Feynman was a very likable and accomplished science communicator. He had little time for philosophy, but his practice of the scientific method is unimpeachable. Of the Feynman TV special above, Nobel Prize-winning chemist Sir Harry Kroto remarked: “The 1981 Feynman-Horizon is the best science program I have ever seen. This is not just my opinion — it is also the opinion of many of the best scientists that I know who have seen the program… It should be mandatory viewing for all students whether they be science or arts students.”

Related Content:

‘The Character of Physical Law’: Richard Feynman’s Legendary Course Presented at Cornell, 1964

Richard Feynman Introduces the World to Nanotechnology with Two Seminal Lectures (1959 & 1984)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness