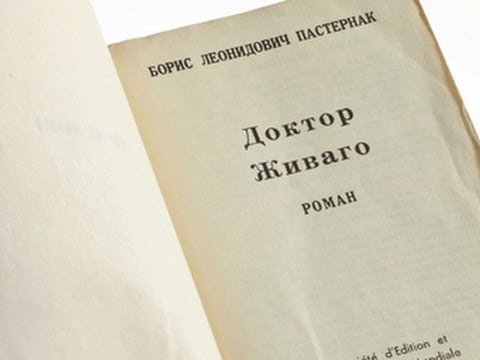

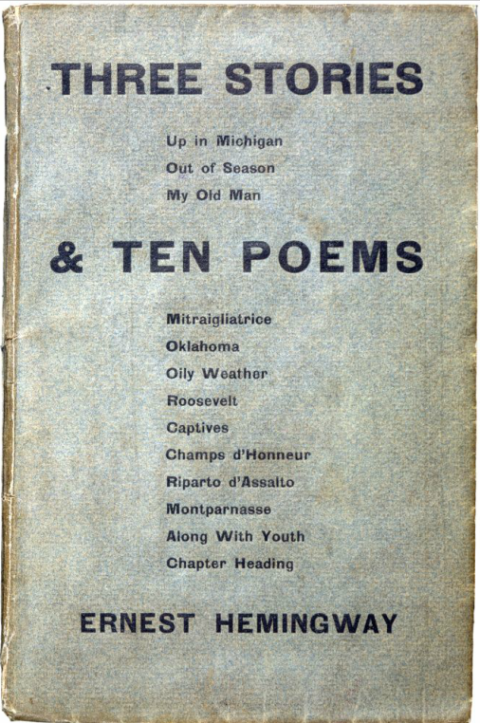

“I like the early stuff”: the classic masculine comment to make about the work of a well-known creator, demonstrating as it does the cultural consumer’s dedication, purism, judgmental rigor, and even endurance (given the relative accessibility, in the intellectual as well as the collector’s senses, of most “early stuff”). Now you have a chance to say it about that most ostensibly masculine of all 20th-century American writers, Ernest Hemingway. Above, see the cover of a coveted edition of the then-young “Papa“ ‘s very first book, 1923’s Three Stories & Ten Poems. The print run numbered only “300 copies, put out by friend and fellow expatriate, the writer- publisher Robert McAlmon,” writes Steve King at Today in Literature. “Both had arrived in Paris in 1921, Hemingway an unpublished twenty-two-year-old journalist with a recent bride, a handful of letters of introduction provided by Sherwood Anderson, and a clear imperative: ‘All you have to do is write one true sentence.’ ”

Instead of shelling out to a rare-book dealer for Three Stories & Ten Poems — admire the sacrifice involved though a true Hemingwayite may — you can read even more of the Old Man and the Sea author’s early stuff in the free e‑book embedded just above: 1946’s The First Forty Nine Stories. It contains not just “Up in Michigan,” “Out of Season,” and “My Old Man,” those three stories of Hemingway’s bound debut, but, yes, 46 more of his earliest published pieces of short-form fiction. Today in Literature quotes one notable contemporary reaction to Three Stories & Ten Poems, from a time before Hemingway had become Hemingway, much less Papa: “I should say that Hemingway should stick to poetry and intelligence and eschew the hotter emotions and the more turgid vision. Intelligence and a great deal of it is a good thing to use when you have it, it’s all for the best.” And who could have written such an astute early assessment of the ultimate literary man’s man? A certain Gertrude Stein.

Related Content:

18 (Free) Books Ernest Hemingway Wished He Could Read Again for the First Time

Seven Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer, 1934

Ernest Hemingway’s Favorite Hamburger Recipe

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.