From the 20/20 point of view of the present, Joseph Stalin was one of the 20th century’s great monsters. He terrified the Soviet Union with campaign after campaign of political purges, he moved whole populations into Siberia and he arguably killed more people than Hitler. But it took decades for the scope of his crimes to get out, mostly because, unlike Hitler, Stalin stuck to killing his own people.

In early 1930s, however, Stalin was considered by many to be the leader of the future. That period was, of course, the nadir of the Great Depression. Capitalism seemed to be coming apart at the seams. The USSR promised a new society ruled not by the oligarchs of Wall Street but by the people — a society where everyone was equal.

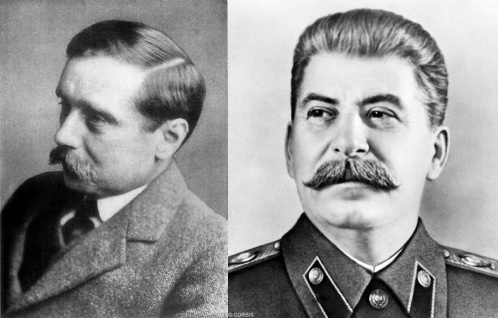

H.G. Wells interviewed Stalin in Moscow in 1934 for the magazine The New Statesman. Wells was an avowed socialist and one of the left’s most influential authors. His first novel, The Time Machine, is essentially an allegory for class struggle after all. The interview between the two is fascinating.

Wells opens the piece by stating that he speaks for the common people. While that point is debatable — Stalin calls him out on that assertion – Wells does speak in a manner that is readily understandable. Stalin, in contrast, speaks in fluent Politburo. The blandness of his speech, choked with Communist boilerplate, seems designed to make the listener tune out. But then he drops little bon mots into his monologues that hint at the violence he has unleashed on his country. Take this line for instance:

Revolution, the substitution of one social system for another, has always been a struggle, a painful and a cruel struggle, a life-and-death struggle.

It’s a chilling line. Especially when you consider that at the time of this interview, Stalin was just starting to launch his first wave of political purges and he was plotting to assassinate his main political rival Sergei Kirov.

As the interview unfolds, you can imagine Wells growing increasingly frustrated by Stalin’s narrow, dogmatic view of the world. The Soviet leader, as Wells later wrote in his autobiography, “has little of the quick uptake of President Roosevelt and none of the subtlety and tenacity of Lenin. … His was not a free impulsive brain nor a scientifically organized brain; it was a trained Leninist-Marxist brain.”

At several points in the interview Wells challenges Stalin: “I object to this simplified classification of mankind into poor and rich,” the author fumes.

And when Stalin doesn’t agree with Wells that the Capitalist system was on its last legs, the author actually chides him for not being revolutionary enough. “It seems to me that I am more to the Left than you, Mr. Stalin; I think the old system is nearer to its end than you think.” Now that’s chutzpah.

In the end, the interview presents a dueling version of the future of the left. Wells believed, in essence, that the Capitalist world only needed to be reformed, albeit drastically, to achieve economic justice. And Stalin argued that Capitalism had to be torn down completely before any other reform could take place.

In spite of their differences, Wells left the interview with a positive impression of the Soviet leader. “I have never met a man more fair, candid, and honest,” he wrote.

Wells died in 1946 before the worst of Stalin’s crimes became known to the outside world. Stalin died in 1953. Following a stroke, his body remained on the floor in a pool of urine for hours before a doctor was called. His minions were terrified that he might wake up and order their execution.

You can read the entire interview between H.G. Wells and Stalin on The New Statesmen’s website here.

via Kottke

Related Content:

Joseph Stalin, a Lifelong Editor, Wielded a Big, Blue, Dangerous Pencil

How to Spot a Communist Using Literary Criticism: A 1955 Manual from the U.S. Military

Leon Trotsky: Love, Death and Exile in Mexico

Learn Russian from our List of Free Language Lessons

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.