Nelson Mandela, who died on December 5, 2013, had spent more than a quarter of his life serving time in various jails. While behind bars for the 18-year period between 1962 and 1980, the anti-apartheid revolutionary educated both himself and others to prepare for the advent of multiracial equality in South Africa. During his confinement at the Robben Island prison, Mandela studied law by correspondence at the University of London, learned Afrikaans to foster a rapport with jailhouse wardens, and was instrumental in launching the “University of Robben Island”, where prisoners possessing expertise in particular fields presented lectures to their fellow inmates.

Mandela’s stay, however, was frequently marred by demeaning and deplorable treatment. Initially, black prisoners were humiliated by being given shorts, commonly worn by children, rather than full-length pants as uniforms. Mandela was also forbidden from wearing sunglasses when forced to labor at a limestone quarry, and the harsh reflections from the rocks damaged his vision. The quarry dust also damaged his tear ducts, which made it impossible for him to cry until receiving corrective surgery in 1994. Perhaps the most painful moments arrived in the late 1960s, when Mandela lost his mother and firstborn son, and was denied permission to attend their funerals.

In spite of these ordeals, Mandela persevered. In an interview with Charlie Rose, above, Morgan Freeman discusses Mandela’s reliance on William Ernest Henley’s 1875 poem, “Invictus,” to keep his hope alive:

“That poem was his favorite… When he lost courage, when he felt like just giving up — just lie down and not get up again — he would recite it. And it would give him what he needed to keep going.”

Freeman, who played Mandela in the 2009 film Invictus, also provides a solemn and dignified recitation of the poem beginning at 3:51. Although the poem is best known for providing succour to Mandela in times of despair, its words of courage have served as inspiration to countless others. Famous figures who have drawn hope from “Invictus” include the father of Burmese opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi during his struggle for Burmese independence and tennis champion Andre Agassi. Rumor has it that U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was also quite fond of it. We’ve included the full text for “Invictus” below:

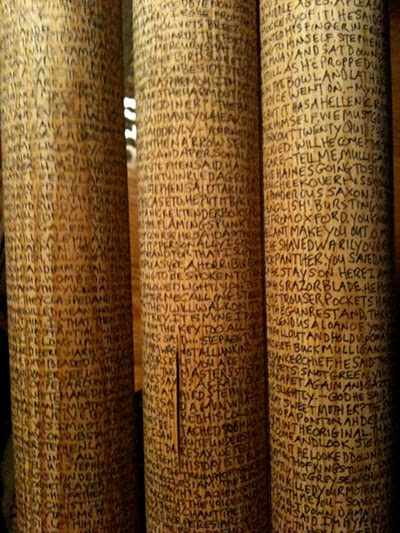

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find, me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll.

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

H/T to Bruno, one of our readers, for sending this video our way.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

Nelson Mandela’s First-Ever TV Interview (1961)

U2 Releases a Nelson Mandela-Inspired Song, “Ordinary Love”

Nelson Mandela Archive Goes Online

Find “Invictus” in our Free Audio Books and Free eBooks collections.