The Strong National Museum of Play, located in Rochester, NY, is a fun children’s museum. But the institution also has serious research archives, stuffed with toys, games, and records of the toy industry. Its online collections, which currently boast 55,068 objects, take a holiday browser on a trip into a figurative grandma’s attic, chock-full of the playthings people loved in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The online archives are divided into four categories: “Toys”, “Dolls”, “Games”, and “More.” Each of these four sections is further subdivided into topically-specific groups, chosen by the archivists.

The collection’s strength is also its weakness: there are so many toys that it can be easy to get overwhelmed. The subject divisions are helpful here. As somebody with an interest in gender and childhood, I found myself fascinated by the housekeeping toys—kids used to use ovens that were heated with real coals!—and that was an easy way to narrow down my browse. Subject groupings for toy soldiers, celebrity dolls, and board games also piqued my interest.

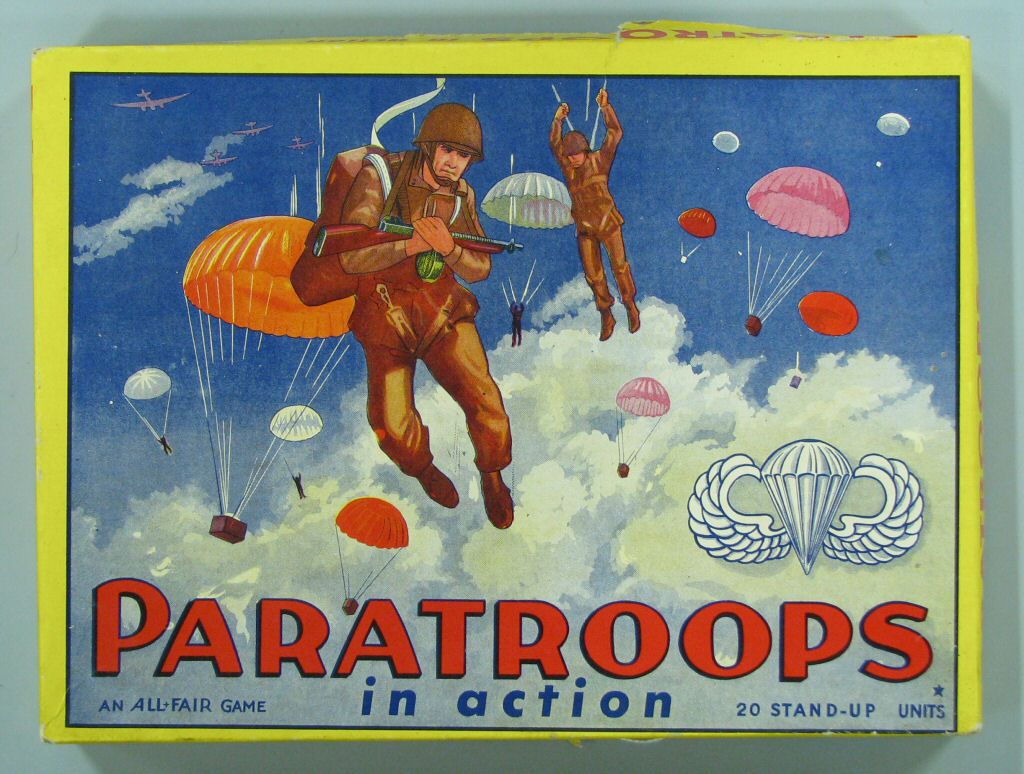

It’s fun to look around for toys from your own childhood (I found a few), but if you’re interested in history, you might find the echoes of historical events to be even more intriguing. Late-nineteenth-century kids played with a paper doll inspired by the circus celebrity Tom Thumb; children of the 1930s had licensed dolls of the media-sensation Dionne Quintuplets; a playset from 1940 featured grim, suited-up “Paratroops in Action.”

Mousing over the thumbnails will allow you to see the item’s name. If you see a blue “Learn More” tag, be sure to click through; that means that the item’s image will be accompanied by an interpretive historical note written by the Strong’s archivists. These vary in length, and contain intriguing tidbits. Did you know, for example, that Holly Hobbie was a real person: the artist Holly Ulinkas Hobbie? Or that the famous artist Charles Dana Gibson had a now-forgotten follower, Nell Brinkley, who illustrated the flapper era?

Rebecca Onion is a writer and academic living in Philadelphia. She runs Slate.com’s history blog, The Vault. Follow her on Twitter: @rebeccaonion.