Philosophers are quirky creatures. Some become household names, in certain well-educated households, without anyone knowing a thing about their lives, their loves, their apartments. The life of the mind, after all, rarely makes for good theater (or TV). And prior to the creation of whole academic departments devoted to contemplation and regional conferences, a philosopher’s life could be a very lonely one. Or so it would seem to those who shun solitude. But for the bookish among us, the glimpses we have here into the well-kept homes and studies of several famous dead male European thinkers may elicit sighs of wonder, or envy even. It was so much easier to keep a room of one’s own neat before computer paraphernalia and tiny sheaves of Post-it notes cluttered everything up, no?

At the top of the post, we have an austere space for a severely austere thinker, Ludwig Wittgenstein. His desk in Cambridge faces a vaulted triptych of sunlit windows, but the bookshelf has clearly been emptied since his stay, unless Herr Wittgenstein preferred to work free of the distraction of other people’s published work. Above, another angle reveals comfortable seating near the fireplace, since blocked up with what appears to be an electric heater, an appliance the ultra-minimalist Wittgenstein may have found superfluous.

In addition to his philosophy, the German scion of a wealthy and eccentric family had an interest in photography and architecture, and he built his sister Margaret a house (above) that became known for “for its clarity, precision, and austerity—and served as a foil for his written work.” Wittgenstein’s eldest sister Hermione pronounced the house unlivable, as it “seemed indeed to be much more a dwelling for the gods than for a small mortal like me.”

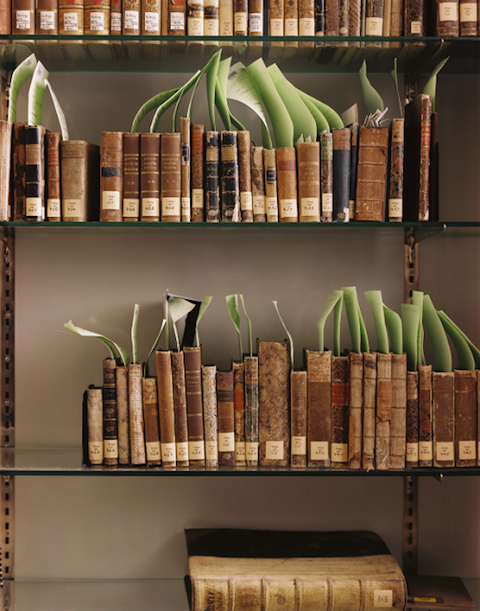

Another polymath, credited along with Goethe for a phase of German thought called Weimar Classicism, poet and philosopher Friedrich Schiller’s studio in his Weimar house above presents us with a light, airy space, a standing desk, and some surprisingly well-tended furnishings. Whether they are original or not I do not know, but the space befits the man who wrote Letters Upon the Aesthetic Education of Man, in which (Fordham University informs us) he “gives the philosophic basis for his doctrine of art, and indicates clearly and persuasively his view of the place of beauty in human life.” The entire house is a study in beauty. A much gloomier character, whose view of humankind’s capacity for rational development was far less optimistic than Schiller’s, Arthur Schopenhauer lived a solitary existence, surrounded by books—a life much more like the caricature of philosophy. Below, see Schopenhauer’s book collection lined up neatly and catalogued.

The façade of Schopenhauer’s birth house in Gdansk, below, doesn’t stand out much from its neighbors, none of whom could have guessed that the strange child inside would prepare the way for Nietzsche and other scourges of the good Christian bourgeoisie. No doubt little Arthur received his portion of ridicule as he shuffled in and out, an odd boy with an odd haircut. And if Schopenhauer didn’t actually write the words attributed to him about the “three stages of truth”—ridicule, violent opposition, and acceptance—he may have fully agreed with the sentiment.

Finally, speaking of Nietzsche, we have below the Nietzsche-Haus in Sils-Maria, Switzerland, where the lover of mountainous climes and hater of the vulgar rabble’s noise holed away to work in the summers of 1881, 1883, and 1888. The house now contains an open library, one of the world’s largest collections of books on Nietzsche. Trip Advisor gives the site four-and-a-half stars, a crowd-sourced score, of course, of which Nietzsche, I’m sure, would be proud.

See many more German (and some French) philosophers’ homes and studies at The Unemployed Philosophers Guild PhLog, A Piece of Monologue, and the excellent photography site of Patrick Lakey.

Related Content:

The Daily Habits of Highly Productive Philosophers: Nietzsche, Marx & Immanuel Kant

Philosopher Portraits: Famous Philosophers Painted in the Style of Influential Artists

Famous Philosophers Imagined as Action Figures: Plunderous Plato, Dangerous Descartes & More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness