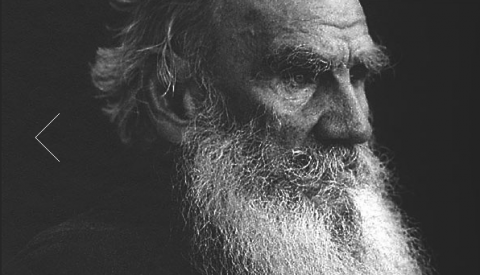

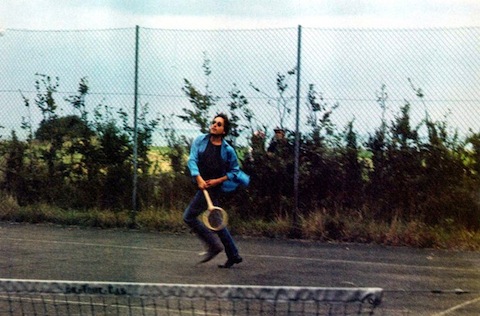

If you do not believe in Captain Beefheart, I doubt the 1974 Old Grey Whistle Test appearance above will convert you. If you are a Beefheart believer, you know. And if you don’t know where you stand on Beefheart, get to know this wild-eyed rock and roll shaman, poet, bluesman, painter, and childhood friend of Frank Zappa. (Start with his fairly straightforward take on Delta blues and sixties garage rock, 1967’s Safe as Milk.)

Beefheart’s Magic Band, a shifting collection of musicians that initially included Ry Cooder (who served as something of a musical director) created some of the most warped music of the last few decades, much of it very recognizably blues-based and much of it (such as the freak outs on Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica) occupying a space all its own—a space that only exists, really, in Captain Beefheart’s head and heart. While Beefheart acquired a reputation as an uncompromising, and singularly demanding, employer of musicians, speaking as a musician, there are few others that I wish I’d had the chance to play with in their heyday.

Despite his demonically inspired weirdness and storied difficulty, what attracted musicians to Beefheart was his ability to push concepts so far beyond the bounds of intelligibility so as to make insanity make perfect sense. Take, for example, his list of instructions, or rather “commandments,” issued to Moris Tepper when the guitarist joined Beefheart’s band in 1976. This is not an obnoxious practical joke—it is the technique of a Zen master, disorienting his student with nonsensical truths mixed in with some very practical advice. Which one is which is for the student to decide.

Captain Beefheart’s “Ten Commandments of Guitar Playing”

1. Listen to the birds

That’s where all the music comes from. Birds know everything about how it should sound and where that sound should come from. And watch hummingbirds. They fly really fast, but a lot of times they aren’t going anywhere.

2. Your guitar is not really a guitar.

Your guitar is a divining rod. Use it to find spirits in the other world and bring them over. A guitar is also a fishing rod. If you’re good, you’ll land a big one.

3. Practice in front of a bush.

Wait until the moon is out, then go outside, eat a multi-grained bread and play your guitar to a bush. If the bush doesn’t shake, eat another piece of bread.

4. Walk with the devil.

Old Delta blues players referred to guitar amplifiers as the “devil box.” And they were right. You have to be an equal opportunity employer in terms of who you’re brining over from the other side. Electricity attracts devils and demons. Other instruments attract other spirits. An acoustic guitar attracts Casper. A mandolin attracts Wendy. But an electric guitar attracts Beelzebub.

5. If you’re guilty of thinking, you’re out.

If your brain is part of the process, you’re missing it. You should play like a drowning man, struggling to reach shore. If you can trap that feeling, then you have something that is fur bearing.

6. Never point your guitar at anyone.

Your instrument has more clout than lightning. Just hit a big chord then run outside to hear it. But make sure you are not standing in an open field.

7. Always carry a church key.

That’s your key-man clause. Like One String Sam. He’s one. He was a Detroit street musician who played in the fifties on a homemade instrument. His song “I Need a Hundred Dollars” is warm pie. Another key to the church is Hubert Sumlin, Howlin’ Wolf’s guitar player. He just stands there like the Statue of Liberty — making you want to look up her dress the whole time to see how he’s doing it.

8. Don’t wipe the sweat off your instrument.

You need that stink on there. Then you have to get that stink onto your music.

9. Keep your guitar in a dark place.

When you’re not playing your guitar, cover it and keep it in a dark place. If you don’t play your guitar for more than a day, be sure you put a saucer of water in with it.

10. You gotta have a hood for your engine.

Keep that hat on. A hat is a pressure cooker. If you have a roof on your house, the hot air can’t escape. Even a lima bean has to have a piece of wet paper around it to make it grow.

If any of the above leads you to think you need to know more about Beefheart, then watch the documentary above, introduced and narrated by the legendary tastemaker John Peel, a true Beefheart believer if one there ever was.

Via Letters of Note

Related Content:

A Young Frank Zappa Plays the Bicycle on The Steve Allen Show (1963)

Frank Zappa Reads NSFW Passage From William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch (1978)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness