Writer and artist Alistair Gentry once proposed a lecture series he called “One Eyed Monster.” Central to the project is what Gentry calls “the cult of James Joyce,” an exemplar of a larger phenomenon: “the vulture-like picking over of the creative and material legacies of dead artists.” “Untalented and noncreative people,” writes Gentry, “are able to build lasting careers from what one might call the Talented Dead.” Gentry’s judgment may seem harsh, but the questions he asks are incisive and should give pause to scholars (and bloggers) who make their livings combing through the personal effects of dead artists, and to everyone who takes a special interest, prurient or otherwise, in such artifacts. Just what is it we hope to find in artists’ personal letters that we can’t find in their public work? I’m not sure I have an answer to that question, especially in reference to James Joyce’s “dirty letters” to his wife and chief muse, Nora.

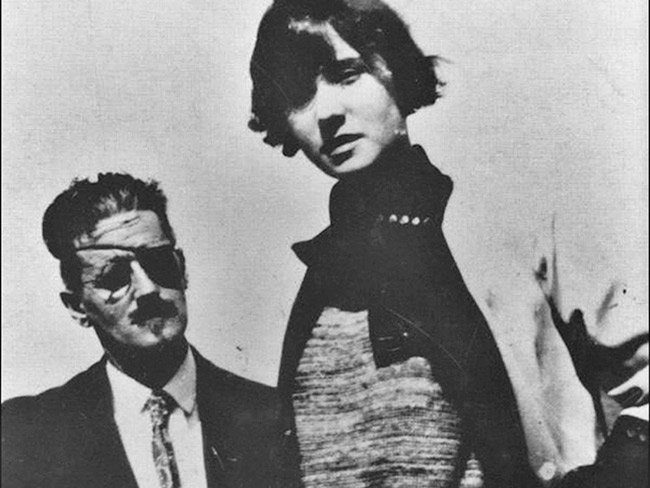

The letters are by turns scandalous, titillating, romantic, poetic, and often downright funny, and they were written for Nora’s eyes alone in a correspondence initiated by her in November of 1909, while Joyce was in Dublin and she was in Trieste raising their two children in very straitened circumstances. Nora hoped to keep Joyce away from courtesans by feeding his fantasies in writing, and Joyce needed to woo Nora again—she had threatened to leave him for his lack of financial support. In the letters, they remind each other of their first date on June 16, 1904 (subsequently memorialized as “Bloomsday,” the date on which all of Ulysses is set). We learn quite a lot about Joyce’s predilections, much less about Nora’s, whose side of the correspondence seems to have disappeared. Declared lost for some time, Joyce’s first reply letter to Nora in the “dirty letters” sequence was recently discovered and auctioned off by Sotheby’s in 2004.

I do not excerpt here any of the language from Joyce’s subsequent letters, not for modesty’s sake but because there is far too much of it to choose from. If those prudish censors of Ulysses had read this exchange, they might have dropped dead from grave wounds to their sense of decorum. As far as I can ascertain, the letters exist in publication only in the out-of-print Selected Letters of James Joyce, edited by pre-eminent Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann, and in a somewhat truncated form on this site. Alistair Gentry has done us the favor of transcribing the letters as they appear in Ellmann’s Selected Letters on his site here. Of our interest in them, he asks:

Does anyone have the right to read things that were clearly meant only for two specific people…? Now that they have been exposed to the world’s gaze, albeit in a fairly limited fashion, does anybody except these two (who are dead) have any right to make objections about or exercise control over the manner in which these private documents and records of intimacy are used?

Questions worth considering, if not answered easily. Nevertheless, despite his critical misgivings, Gentry writes: “These letters stand on their own as brilliant and, dare I say, arousing Joycean writing. In my opinion they’re definitely worth reading.” I must say I agree. Joyce’s brother Stanislaus once wrote in a diary entry: “Jim is thought to be very frank about himself but his style is such that it might be contended that he confesses in a foreign language—an easier confession than in the vulgar tongue.” In the “dirty letters,” we get to see the great alchemist of ordinary language and experience practically revel in the most vulgar confessions.

Related Content:

James Joyce Plays the Guitar, 1915

On Bloomsday, Hear James Joyce Read From his Epic Ulysses, 1924

James Joyce, With His Eyesight Failing, Draws a Sketch of Leopold Bloom (1926)

James Joyce’s Ulysses: Download the Free Audio Book

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness