Many things have happened on the internet this week, among them some get off my lawn outrage at a $375 Urban Outfitters leather jacket designed to replicate the homemade swag every punk rock kid once draped over their shoulders. Then there’s the Justin Bieber/Black Flag mash-up t‑shirt that “ruined punk forever.” I may have spent some formative years immersed in ersatz punk and hardcore culture, but no matter how old and cranky I may be compared to the target market of this merchandise, I just can’t bring myself to get bothered. No one has said it better than Dave Berman: “punk rock died when the first kid said / ‘punk’s not dead, punk’s not dead.’”

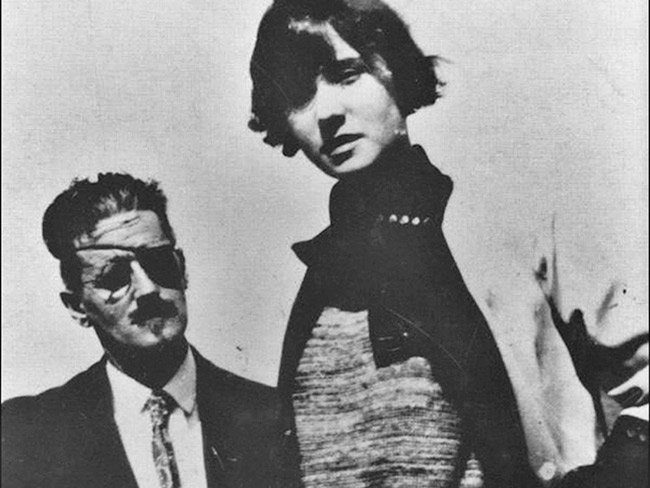

The strident desire of some to cling to a punk rock ethos can be amusing since the movement’s most famous figureheads, the Sex Pistols, crashed and burned a little over three years after forming and one year after introducing their mascot, Sid Vicious. The band’s creative destruction often seems like the most viable expression of punk. It burns itself out on its own energy. Everything else you can say about it is just more Malcolm McLaren marketing.

Or, put differently, maybe the only discussion worth having about punk rock is archival. It came, it went, get over it—but oh, what a glorious comet trail left by the likes of Johnny Rotten! And we have evidence of the tail end on film. Above, you can see the Pistols very last performance at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom in January of 1978.

The film opens with text excusing some quality control issues: “The footage contained in this video is rare archive material and irreplaceable. The publishers feel that the quality of the content… far outweighs any minor… shortcomings of sound and vision.” Then we’re off to the races, introduced by a pair of announcers, male and female, like an Olympic event. Despite the disclaimer, this is decent film and audio, and definitely “quality content.” Brilliant, in fact (Sid actually plays!), and an excellent argument for why this band needed no future. A YouTube commenter helpfully breaks down the video into the tracklist below. Great stuff.

01:45 — God Save The Queen , 05:56 — I Wanna Be Me , 10:04 — Seventeen , 12:27 — New York , 15:54 — EMI , 19:38 — Belsen Was Gas , 21:50 — Bodies , 25:50 — Holidays In The Sun , 31:17 — Liar , 35:40 — No Feelings , 38:55 — Problems , 43:26 — Pretty Vacant, 46:57 — Anarchy In The UK , 52:43 — No Fun

Related Content:

Malcolm McLaren: The Quest for Authentic Creativity

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness