Click images for larger versions

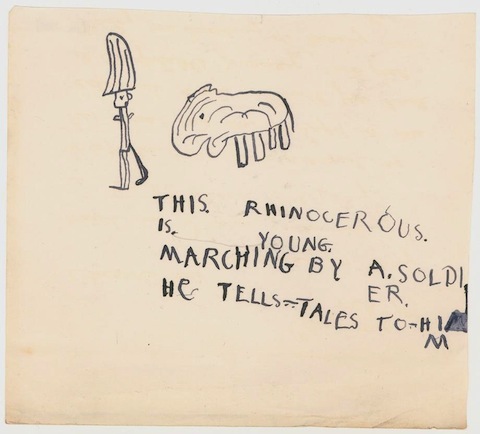

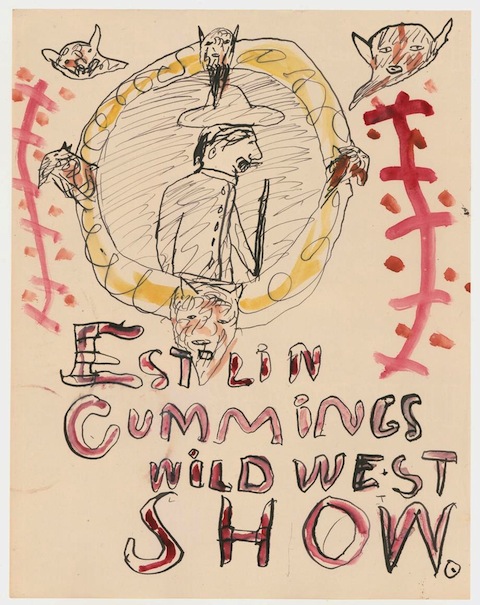

Rebecca Onion over at Slate’s history blog “The Vault” has brought to our attention two delightful finds from the Massachusetts Historical Society: childhood drawings by poet and painter E.E. Cummings, made when he was 6 and 7 years old. Dating from 1900–1902, the sketches, writes Onion, “reflect Cummings’ immersion in the popular culture of the time: circuses, Wild West shows, and adventure fiction.” These two drawings are fascinating portraits of the young Cummings’ mind at work. What a young mind he had.

Cummings began writing poetry at age 8, and wrote a poem a day until he was 22. His mature work, which he began publishing after his release from an internment camp in Normandy during WWI (where he was held for suspected treason), shows the same kind of childlike playfulness and discipline. And while the drawing at the top is the work of a young boy struggling with the conventions of the written word, its oddly-spaced and punctuated text—the lexical and syntactical ambiguities created by the layout—could certainly have come from the pen of the adult poet. Cummings’ ideas about his poetry were deliberately idiosyncratic and forcefully individual. As he would write, “may I be I is the only prayer—not may I be great or good or beautiful or wise or strong.” Or, as he expressed in a similar sentiment in his 1926 collection, is 5, perhaps in response to some critical opprobrium:

mr youse needn’t be so spry

concernin questions arty

each has his tastes but as for i

i likes a certain party

In the drawing above, the young Edward Estlin Cummings imagines himself as a Buffalo Bill-like character. Onion points us toward the adult Cummings’ darkly ironic poem “[Buffalo Bill ‘s],” as a companion to the boy Cummings’ starry-eyed self-fashioning and “hero worship.” While on a superficial reading, Cummings’ work can sometimes seem maddeningly childish and silly, poems like “[Buffalo Bill ‘s]” show him plucking apart naïve illusions about heroism and spectacle as in so many of his other poems he skewers the pretensions of urban sophisticates and tastemakers, promoting a Romantic, uninhibited idea of the self unfettered by social, and typographical, conventions.

Cummings would be very appreciative of the work the Massachusetts Historical Society has done in cataloguing his family papers; he had a deep respect for history—above all for personal history. In the first of his so-called “nonlectures,” delivered at Harvard in 1952, he refers to his “autobiographical problem” in a passage that conjures the dystopian visions of Huxley and Orwell:

There’d be no problem, of course, if I subscribed to the hyperscientific doctrine that heredity is nothing because everything is environment; or if (having swallowed this supersleepingpill) I envisaged the future of socalled mankind as a permanent pastlessness, prenatally enveloping semiidentical supersubmorons in perpetual nonunhappiness. Rightly or wrongly, however, I prefer spiritual insomnia to psychic suicide.

Perhaps Cummings could thank “spiritual insomnia” for his serious wordplay and boundless curiosity—two childhood traits he never let go of.

Related Content:

The Art of Sylvia Plath: Revisit Her Sketches, Self-Portraits, Drawings & Illustrated Letters

Dylan Thomas Sketches a Caricature of a Drunken Dylan Thomas

William S. Burroughs Shows You How to Make “Shotgun Art”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness