Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard—often considered the first existentialist—was born 200 years ago this past Sunday in Copenhagen. Writing under pseudonyms like Johannes Climacus and Johannes de Silentio, Kierkegaard attacked both the idealism of contemporary philosophers Hegel and Schelling and the bourgeois complacency of European Christendom. A highly skilled rhetorician, Kierkegaard preferred the indirect approach, deploying irony, ridicule, parody and satire in a paradoxical search for individual authenticity within a European culture he saw as beset by self-important puffery and unthinking mass movements.

While millions of readers have embraced Kierkegaard’s probing method, as many have also rejected his faith-based conclusions. Nevertheless, his strikingly eccentric skewering of the tepidly faithful and overly optimistic breathed light and heat into the nineteenth century debates among modern Christians as they confronted the findings of science and the challenges posed by world religions and materialist philosophers like Karl Marx.

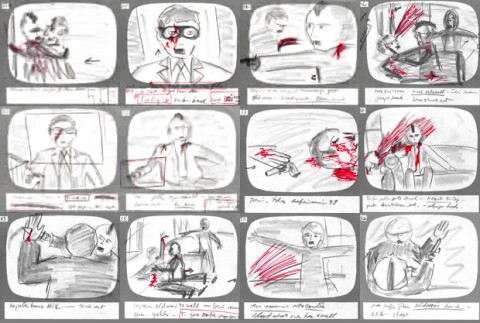

Marx and Kierkegaard’s many contrasts and contradictions are well represented in Episode 4 of the BBC documentary series Sea of Faith, “Prometheus Unbound” (part one at top, part two immediately above). The 1984 six-part series—named in reference to Matthew Arnold’s famous poem “Dover Beach” and hosted by radical theologian Don Cupitt—examines the ways in which the Copernican and Darwinian scientific revolutions and the work of critics of religious doctrine like Freud, Marx, Nietzsche, Strauss, and Schweitzer shook the foundations of orthodox Christianity. Here, Kierkegaard is played in reenactments with appropriate intensity by British actor Colin Jeavons.

You can learn more about the documentary series (and purchase DVDs) here. And for more on Kierkegaard, you would be well-served by listening to Walter Kaufmann’s lecture above. For a lighter-hearted but still rigorous take on the philosopher, be sure to catch the well-read, irreverent gents at the Partially Examined Life podcast in a discussion of Kierkegaard’s earnest and often disturbing defense of existential Christianity, The Sickness Unto Death.

You can find more philosophy documentaries in our collection, 285 Free Documentaries Online.

Related Content:

Download Walter Kaufmann’s Lectures on Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Sartre & Modern Thought (1960)

Existentialism with Hubert Dreyfus: Four Free Philosophy Courses

Friedrich Nietzsche & Existentialism Explained to Five-Year-Olds (in Comical Video by Reddit)

Free Online Philosophy Courses

135 Free Philosophy eBooks

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness