Deities, conspiracies, politics, space aliens: you don’t actually have to believe in these to find them interesting. Just focus your attention not on the things themselves, but in how other people regard them, what they say when they talk about them, and why they think about them the way they do. Psychotherapist and onetime Freud protégé Carl Gustav Jung treated UFOs this way when he wrote his book Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies, which examines “not the reality or unreality” of the titular phenomena, but their “psychic aspect,” and “what it may signify that these phenomena, whether real or imagined, are seen in such numbers just at a time” — the Cold War — “when humankind is menaced as never before in history.” As what Jung called a “modern myth,” UFOs qualify as real indeed.

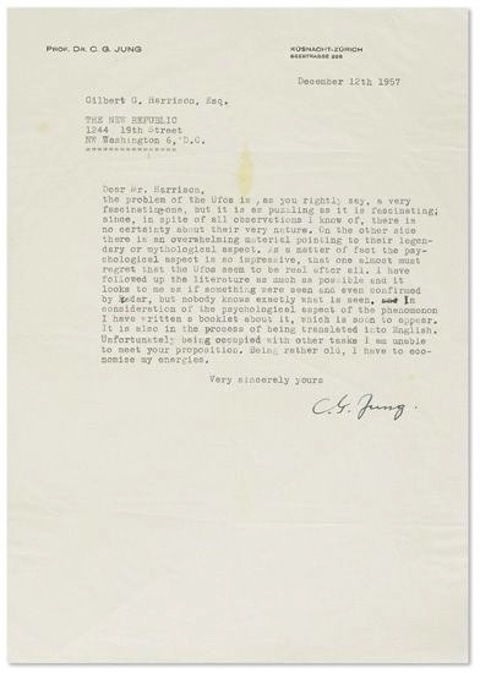

In 1957, with Flying Saucers to appear the following year, New Republic editor Gilbert A. Harrison wanted to get this Jungian perspective on UFOs in his magazine. At the top of this post, you can see (via The Awl) a scan of Jung’s response to Harrison’s query, the text of which follows:

the problem of the Ufos is, as you rightly say, a very fascinating one, but it is as puzzling as it is fascinating; since, in spite of all observations I know of, there is no certainty about their very nature. On the other side, there is an overwhelming material pointing to their legendary or mythological aspect. As a matter of fact the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the Ufos seem to be real after all. I have followed up the literature as much as possible and it looks to me as if something were seen and even confirmed by radar, but nobody knows exactly what is seen. In consideration of the psychological aspect of the phenomenon I have written a booklet about it, which is soon to appear. It is also in the process of being translated into English. Unfortunately being occupied with other tasks I am unable to meet your proposition. Being rather old, I have to economize my energies.

Jung, as you can see, doubled his own interest in the subject by not only considering flying saucers a social phenomenon, but as a real physical phenomenon as well. Serious enthusiasts of both Jung and UFOs might consider bidding on the original letter, now up for auction. Estimated sale price: $2,000 to 3,000.

Related Content:

Face to Face with Carl Jung: ‘Man Cannot Stand a Meaningless Life’

Carl Gustav Jung Ponders Death

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.