Now Little Johnny Jewel,

Oh, he’s so cool,

He has no decision,

He’s just trying to tell a vision

So go the first lines of “Little Johnny Jewel,” the first single from brilliant New York free-jazz punk band Television, written in tribute to James Newell Osterberg, better known as Iggy Pop. The song’s release in 1975 sadly coincided with the final breakup of Pop’s groundbreaking Detroit proto-punk garage band The Stooges, after which the self-destructive frontman checked himself into a mental institution to get clean. Maybe it seemed that the vision was spent, and might have been had David Bowie not stepped in, swept Pop away to Berlin, and helped him produce his first solo album, 1977’s The Idiot, quickly followed by the return to raw form, Lust for Life (with its demented cover art of a grinning Pop, looking for all the world like the high school yearbook photo of a burned-out future serial killer).

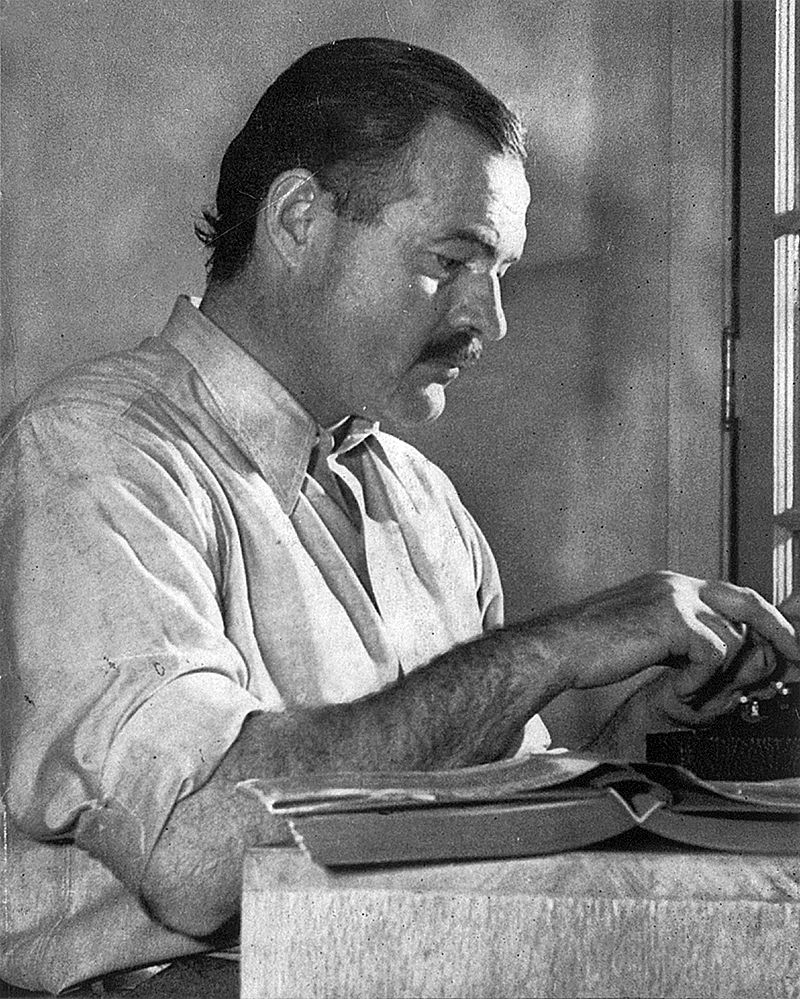

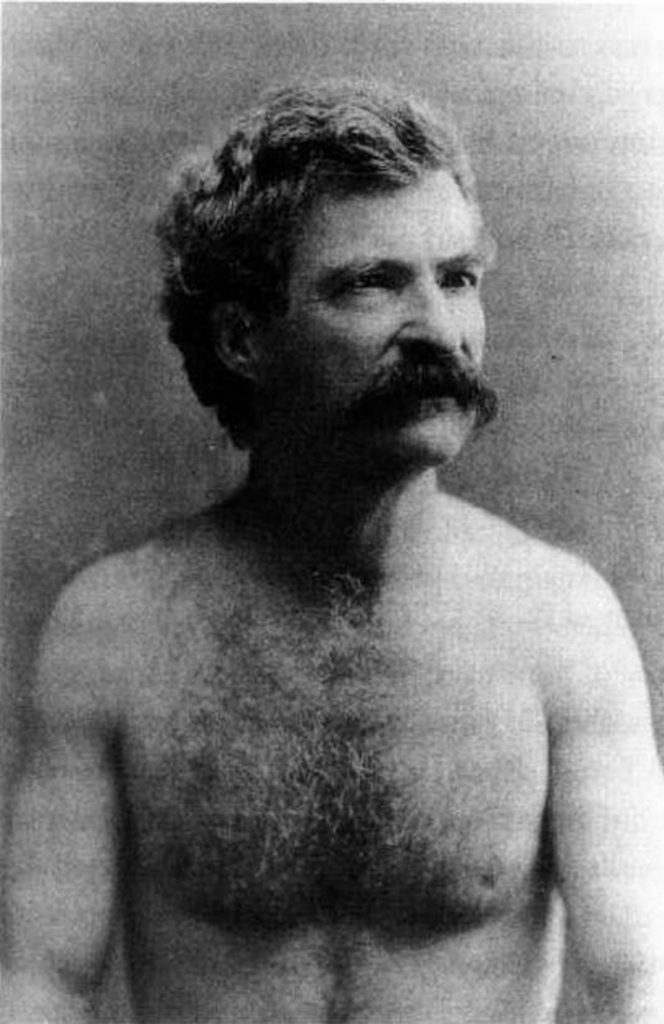

By 1986, Pop had cemented his status as a solo artist, Bowie collaborator, and esteemed forefather of punk and new wave, releasing the Bowie-produced Blah Blah Blah, with its single “Real Wild Child.” It’s at this point in his career that the Dutch film above, Lust for Life, caught up with him. The documentary opens with a captivating live performance of the title song from an ’86 show in Utrecht. Pop describes his sound as emanating from Motor City’s “industrial hum” and his encounter with Chicago blues. Later, Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton takes us on a tour of a University of Michigan ballroom where Elektra records scout, rock journalist, and punk impressario Danny Fields discovered and signed The Stooges in 1968. The late Asheton plays a significant role in the film, demonstrating the Stooges guitar sound and opening up about the band’s rise and demise. From there, we’re transported via some vintage, grainy footage to a Stooges gig, with a shirtless Iggy emerging from the crowd after a stage-dive (he gets credit for inventing the move).

The Stooges material provides crucial context for the emergence of Iggy Pop from the gritty Detroit garage-rock scene (which included another seminal proto-punk band, the MC5, with whom the Stooges often played). In one interview clip Pop explains in detail how he developed his songwriting with Asheton, drawing from Johnny Cash, the Rolling Stones, Velvet Underground, his own experiments with poetry, and the dull grind of Midwestern life. These animated interviews are priceless windows on the early influences of the so-called “godfather of punk,” situating The Stooges as emerging directly from late-sixties psychedelic rock. In some ways, Detroit bands like The Stooges and the MC5 (like Black Sabbath in England)—with their abrasive noise-rock cacophony, near-metal crunch, and minimalist blues foundations—provide the missing link between sixties rock and roll and punk. Stripping the former of its excesses and drawing on raw blues and country sentiment and loads of late-20th century disaffection, they took the nihilism in songs like The Stones’ “Street Fighting Man” to its logical conclusion. That seems, at least, the underlying premise of the film, and it makes a good case.

While the documentary’s few minutes of narration are in Dutch, the majority of Lust for Life is cut together from English-language interviews and old performance footage of Iggy and The Stooges. One rare clip has Pop in a black-and-white TV talk show interview comparing Johnny Rotten to Sigmund Freud, then standing and taking a bow to a guffawing audience. It’s a classic Iggy Pop moment, that alluring combination of erudition, showmanship, unsettling weirdness, and sheer taking-the-piss. Underneath the seemingly unhinged chaos and madness of Iggy Pop’s stage show has always lay a wicked intelligence, uncompromising work ethic, and pummeling drive to “tell a vision.”

Nearly thirty years after Television’s nod to Jim Osterberg, Henry Rollins—another usually-shirtless, hyperkinetic punk frontman—vividly described the qualities above in his spoken word tribute to Iggy, the survivor who still puts most rock stars to shame (from Rollins’ 2004 DVD Live at Luna Park). Rollins tells a hilarious story of how Pop blew his mind (and destroyed the stage) in a 1992 show opening for the Beastie Boys, which sparked Rollins many attempts to compete with his idol. After hearing the real thing, tell me what you think of Rollins’ Iggy Pop impression.

Related Content:

The Story of Ziggy Stardust: How David Bowie Created the Character that Made Him Famous

Christopher Walken, Iggy Pop, Debbie Harry & Other Celebs Read Tales by Edgar Allan Poe

Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen Take Phone Calls on New York Cable TV (1978)

Josh Jones is a writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness