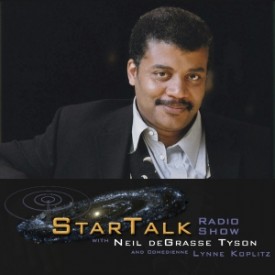

Neil deGrasse Tyson has a podcast. I repeat, Neil deGrasse Tyson has a podcast. If you’re unfamiliar (and you shouldn’t be), Tyson is Astrophysicist-in-residence at New York’s Natural History Museum and Director of its Hayden Planetarium. He’s also the most prominent advocate for a revitalized U.S. space program. Okay, back to the podcast. As an avid consumer of every science-based podcast out there, I can tell you that the StarTalk Radio Show (iTunes — Feed — Web Site) has quickly risen to the top of my list. The very personable Tyson is the big draw, but he has also made the wise decision to include “comedian co-hosts, celebrities, and other special guests.” In the episode right below, Tyson and comedian Eugene Mirman (whom you might recognize as the voice of Gene from Bob’s Burgers) mix it up with video game designer Will Wright and author Jeff Ryan.

Neil deGrasse Tyson has a podcast. I repeat, Neil deGrasse Tyson has a podcast. If you’re unfamiliar (and you shouldn’t be), Tyson is Astrophysicist-in-residence at New York’s Natural History Museum and Director of its Hayden Planetarium. He’s also the most prominent advocate for a revitalized U.S. space program. Okay, back to the podcast. As an avid consumer of every science-based podcast out there, I can tell you that the StarTalk Radio Show (iTunes — Feed — Web Site) has quickly risen to the top of my list. The very personable Tyson is the big draw, but he has also made the wise decision to include “comedian co-hosts, celebrities, and other special guests.” In the episode right below, Tyson and comedian Eugene Mirman (whom you might recognize as the voice of Gene from Bob’s Burgers) mix it up with video game designer Will Wright and author Jeff Ryan.

Ryan’s Super Mario: How Nintendo Conquered America—and the history of video games more generally—is the topic of the show. Despite the less-than-stellar audio quality, this is not to be missed. The conversation is rapid-fire: Mirman interjects hilarious inanities while Wright and Ryan speed through the fascinating history and Tyson throws knuckleball questions and enthuses (at 4:30) that the “first real video game,” Space Wars, was about, what else, space. We also get the history of the unforgettable Pong (at 5:59), the original Star Wars game (at 8:17), and, naturally, Donkey Kong (at 3:19), designed by the now wildly famous (in Japan, at least) Shigeru Miyamoto–who also invented Mario, and who had never designed a game in his life before Donkey Kong. All this and some classic 8‑bit video game music to boot.

StarTalk in general has much to recommend it. Tyson is the “nation’s foremost expert on space,” and is probably instantly recognizable from his hosting of NOVA scienceNow and his bestselling books. He is the public face of a scientific community often in need of good press, and he has the rare ability to translate abstruse concepts to the general public in a humorous and approachable way. Previous guests/co-hosts have included Janeane Garofalo (in the “most argumentative Startalk podcast ever”) and John Hodgman (of the Daily Show and the “Mac vs. PC” ads). But above all, c’mon, it’s Neil deGrasse Tyson. The man deservedly has his own internet meme, inspired by his dramatic gestures in this video discussion of Isaac Newton from Big Think.

Enough said.

Watch the full Big Think interview with Tyson here. And don’t forget to subscribe to the StarTalk Radio Show (iTunes — Feed — Web Site).

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.