Did the United States of America lose much of its will to explore outer space when the Soviet Union’s collapse shut off the engine of competition? Critical observers sometimes make that point, but I have an alternative theory: maybe the decline of progressive rock had just as much to do with it. Both that musical subgenre and American space exploration proudly possessed their distinctive aesthetics, the potential for great cultural impact, and ambition bordering on the ridiculous. Though we didn’t have mash-ups in the years when shuttle launches and four-side concept albums alike captured the public imagination, we can now use modern technology to double back and directly unite these two late-twentieth-century phenomena. Behold, above, Pink Floyd’s jam “Moonhead” lined up with footage of Apollo 17, NASA’s last moon landing.

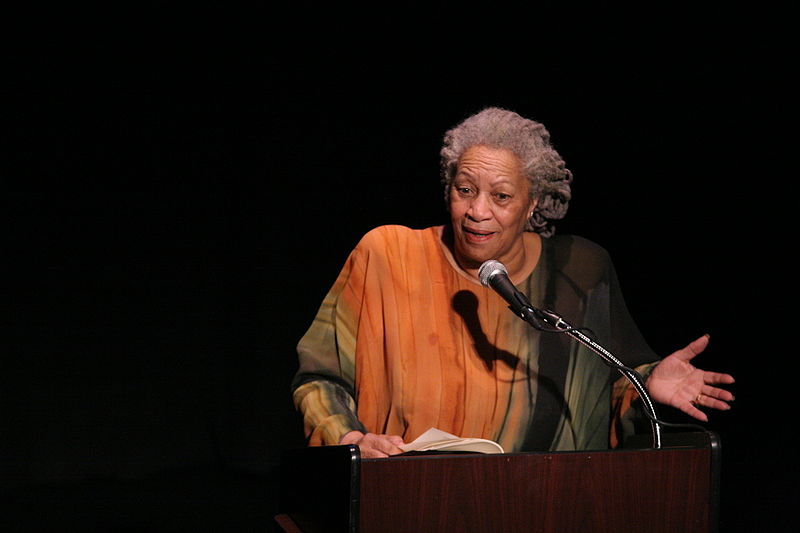

But given the recent passing of astronaut Neil Armstrong, none of us have been thinking as much about the last moon landing as we have about the first. Pink Floyd actually laid down “Moonhead” at a BBC TV studio during the descent of Apollo 11, the mission on which Armstrong would take that one giant leap for mankind. The band’s improvisation made it to the ears of England’s moon-landing viewers: “The programming was a little looser in those days,” remembers guitarist David Gilmour, “and if a producer of a late-night programme felt like it, they would do something a bit off the wall.” British rock’s fascination with space proved fruitful. David Bowie put out the immortal “Space Oddity” mere days before Apollo 11’s landing (to say nothing of “Life on Mars?” two years later), and the BBC played it, too, in its live coverage. Even as late as the early eighties, no less a rock innovator than Brian Eno, charmed by American astronauts’ enthusiasm for country-western music, would craft the album Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks. If we want more interesting popular music, perhaps we just need to get into space more often.

via NYTimes and BoingBoing

Related content:

Remembering Neil Armstrong, the First Man on the Moon, with Historic Footage and a BBC Bio Film

Mankind’s First Steps on the Moon: The Ultra High Res Photos

Dark Side of the Moon: A Mockumentary on Stanley Kubrick and the Moon Landing Hoax

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.