Johnny Cash wrote down at least two lists in his lifetime. Let’s start with the big one. In 1973, when his daughter Roseanne turned 18, the legendary musician pulled out a sheet of yellow legal paper and began writing down 100 Essential Country Songs, the songs she needed to know if she wanted to start her own musical career. The list, writes the website FolkWorks, didn’t construe country music narrowly. It was eclectic, taking in old folk songs, Appalachian ballads, and also protest songs, early country classics, and modern folks songs sung by artists like Bob Dylan. (Don’t miss our post on Dylan and Cash’s 1969 collaboration here.) This essential list never went public, at least not in full. Roseanne Cash guarded it closely until 2009, when she released an album featuring interpretations of 12 titles from her father’s list. The other 88 songs still remain a mystery.

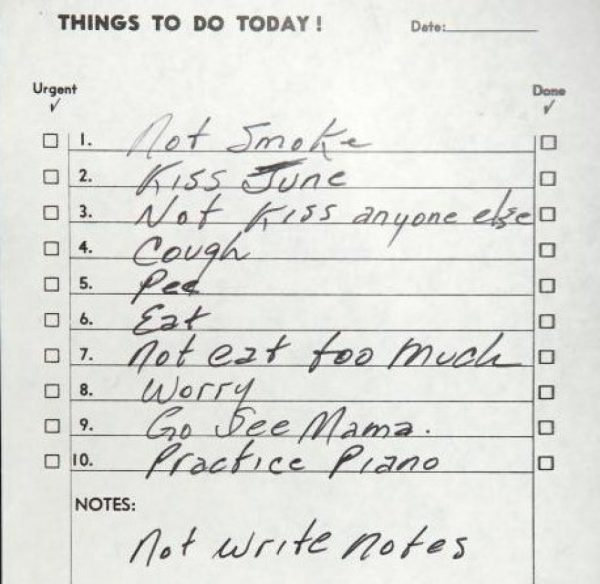

Now on to that other list: Somewhere along the way (we’re not sure when) The Man in Black jotted down 10 “Things to Do Today!” This list feels almost like something you and I could have written, the stuff of mortals. Heck, in a given day, we all “Cough,” “Eat” and “Pee.” We struggle with will power (not eating too much, perhaps not smoking, maybe not fooling around with anyone but our spouse). And we’re hopefully good to our loved ones. So what sets Johnny Cash apart from us? Just June and that piano.

Johnny’s to-do list sold at auction for $6,250 in 2010.

via The New York Times via Lists of Note

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!