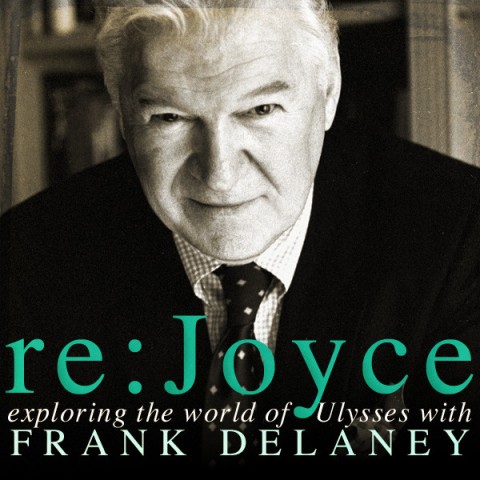

If you need someone to host a multi-decade podcast on James Joyce’s Ulysses, then why settle for less than the most eloquent man in the world? Visit Frank Delaney’s site, and you’ll find it less than shy about proclaiming that National Public Radio once dubbed him just that. A prolific man of letters, Delaney has in his 42-year-long career logged time as a newsreader, book journalist, interviewer, Edinburgh Festival Literature Director, talk show host, Man Booker Prize judge, radio broadcaster, novelist, and historian. In 1981, his book James Joyce’s Odyssey brought his surpassing enthusiasm for Joyce scholarship to public attention, and it took a whole new form on, appropriately enough, Bloomsday 2010, when Delaney added the title of podcaster to his résumé by launching Re: Joyce (iTunes — RSS). The show operates on a simple concept: each Wednesday, Delaney deconstructs a piece of Ulysses, usually for four to fifteen minutes. This will run, so the plan goes, for the next twenty-two years.

An ambitious project, certainly, but I find that podcasting, especially literary podcasting, could always use a little more ambition. “Why?” Delaney asks of the show on its debut episode. “Well, why not? You could say, ‘Why bother?’ And I would say, for the sheer fun of it. Because this is a book that has engrossed and delighted me for most of my adult life, and I know the enjoyment to be had from it. And I also know that such enjoyment has been denied to many, many people who would read Ulysses if they weren’t so daunted by it, and indeed, who tried to read it but had to give up. How do I know this? Because I was one of them.” If this sounds a little like the script of an infomercial, Delaney embraces the sensibility, labeling Re: Joyce his “infomercial for Ulysses.” As far as eloquence — and erudition, not to mention richness of subject matter — he’s certainly surpassed Ron Popeil.

You can download the podcast from iTunes for free or follow the RSS feed here. Copies of Joyce’s Ulysses can be found in our collections of Free eBooks and Free Audio Books. The first episode of Re:Joyce appears below:

Related content:

James Joyce Manuscripts Online, Free Courtesy of The National Library of Ireland

Stephen Fry Explains His Love for James Joyce’s Ulysses

James Joyce’s Ulysses: Download the Free Audio Book

Henri Matisse Illustrates 1935 Edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.