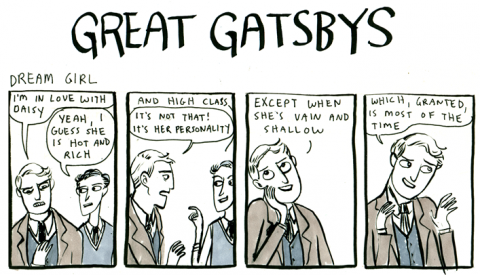

Listen, Old Sport, as far as that Leonardo DiCaprio Gatsby movie goes, I haven’t seen it. But I’ll bet a swimming pool of gin it’s nowhere near as funny as cartoonist Kate Beaton’s 3‑panel takes on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel.

Of course, F. Scott’s original wasn’t exactly what one would call a knee slapper — whereas Beaton’s comic collection, Hark! A Vagrant, merits a permanent spot in one’s bathroom library. Beaton’s take on The Great Gatsby is by no means a literal adaptation, but her mean-faced, venom-tongued creations get it spiritually right. They also do a number on Bronte, Jane Austen, Nietzsche and Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, to name but a few of the author’s other literary targets. (See her archive here.) Not bad for a Canadian with degrees in History and Anthropology. Is it wrong to think Zelda would approve?

At any rate, it’s high time someone blew the lid off of what’s behind the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckelberg. Gratifying, too, to see Tom and Daisy’s child getting some long past due consideration. Now that I think about it, our compulsion to keep beating on boats against the current is kind of funny. Top drawer stuff, Old Sport, top drawer stuff.

Find works by F. Scott Fitzgerald in our collections of Free Audio Books and Free eBooks.

Related Content:

Philosophy Made Fun: Read the Free Preview Edition of the Action Philosophers! Comic

- Ayun Halliday is the author of a half dozen some books including No Touch Monkey! And Other Travel Lessons Learned Too Late.