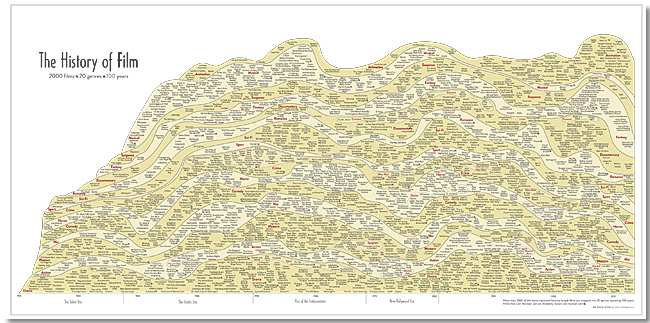

First we have a film, the 1960 piece — some would say pinnacle — of psychological horror, Psycho. Then we have a man, Alfred Hitchcock, Psycho’s director, the famously mannered but seemingly troubled master craftsman of midcentury cinematic suspense. Then we have a book, Stephen Rebello’s Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, which Anthony Perkins, who played the psycho, called “required reading not only for Psycho-files, but for anyone interested in the backstage world of movie-creation.” And, next week, we’ll have a new period drama, set during the production of the film, based on the book, and centered on the man. It’s impossible to imagine the aficionado of twentieth-century motion pictures who wouldn’t want to watch Anthony Hopkins take on Hitchcock’s title role. Behold the brief clip above, wherein Hopkins-as-Hitchcock explains to young Janet Leigh how, exactly, he plans to shoot the shower scene, as his wife Alma looks nervously on.

You’ll notice, in the roles of Janet Leigh and Alma Reville, two more well-respected performers, Scarlett Johansson and Helen Mirren. Indeed, the list of actors involved in Hitchock and that of characters they play look equally interesting: A Serious Man star Michael Stuhlbarg as talent agent Lew Wasserman, Karate Kid Ralph Macchio as screenwriter Joseph Stefano, Wallace Langham as graphic artist and title designer Saul Bass, and Michael Wincott as real-life serial killer Ed Gein. In the clip just above, watch Hitchcock explain to Alma his insistence upon self-financing Psycho’s production after getting turned down by Paramount: “Do you remember the fun we had when we started out, all those years ago?” he asks. “We didn’t have any money then, did we? We didn’t have any time, either, but we took risks, do you remember? We experimented. We invented new ways of making pictures, because we had to. I just want to feel that kind of freedom again.” Before seeing exactly how he enjoyed that freedom again when Hitchcock comes out on November 23rd, be sure to revisit our posts featuring Psycho’s tantalizing original trailer, and the filmmaker’s own rules for watching the movie.

Related content:

22 Free Hitchcock Movies Online

Martin Scorsese Brings “Lost” Hitchcock Film to Screen in Short Faux Documentary

François Truffaut’s Big Interview with Alfred Hitchcock (Free Audio)

Hitchcock on Happiness

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.