We’ve written before about the public service Leonard Bernstein rendered the American public as an ambassador of classical music. Bernstein made some appearances on an arts and culture program called Omnibus in the 50s, and in 1972, as the Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard, he delivered a masterful series of public lectures. Through his various appearances on radio and television programs, he succeeded brilliantly in making high art accessible to the average person. In January of 1958, just two weeks after taking over duties as the director of the New York Philharmonic, Bernstein took up a tradition in American orchestras called “young people’s concerts.” He would lead a total of 53 such concerts, even after his tenure at the Philharmonic ended in 1969, continuing as conductor emeritus until 1972. The concerts were first broadcast on Saturday mornings, but for a few years, CBS—probably in reaction to FCC director Newton Minow’s 1961 “vast wasteland” speech about the state of television—moved the program to prime time. Bernstein made the concerts central to his work at the Philharmonic, describing them in hindsight as “among my favorite, most highly prized activities of my life.”

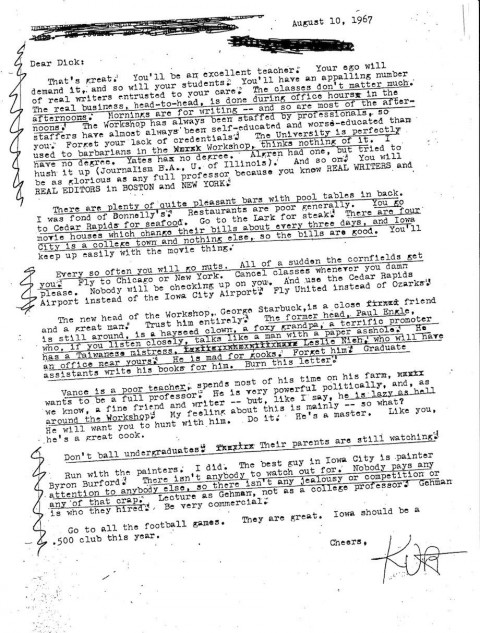

The first concert (above), entitled “What Music Means,” begins with Rossini’s “William Tell Overture.” While the orchestra works away with precision, the camera cuts to the faces of astonished kids reacting to what they knew at the time as the theme to The Lone Ranger TV show. Bernstein then stops the piece, the kids cry out “Lone Ranger!” and he deftly pivots from this disarming moment to a fascinating discussion of why music isn’t about “stories,” isn’t about “anything, it just is.” He communicates his formalist theory without dumbing-down or condescension, but with clarity and passion. Stripping away the popular notion that every work of art has some inherent “meaning” (or “hidden,” or “deep” meaning), Bernstein shows his young audience instead how all art–“high” or “low”–is first and foremost about aesthetic pleasure, and appreciation begins with an understanding of how any given work can only appeal to our emotions through the senses. Music, Bernstein insists, is just “made of notes.”

This concert, at Carnegie Hall, was the first of its kind to be televised. Later episodes marked the first concerts to be televised from New York’s Lincoln Center. The remaining three parts of “What Music Means” are available here (Part 2, Part 3, Part 4), and a full version (with Spanish subtitles) can be found here.

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.