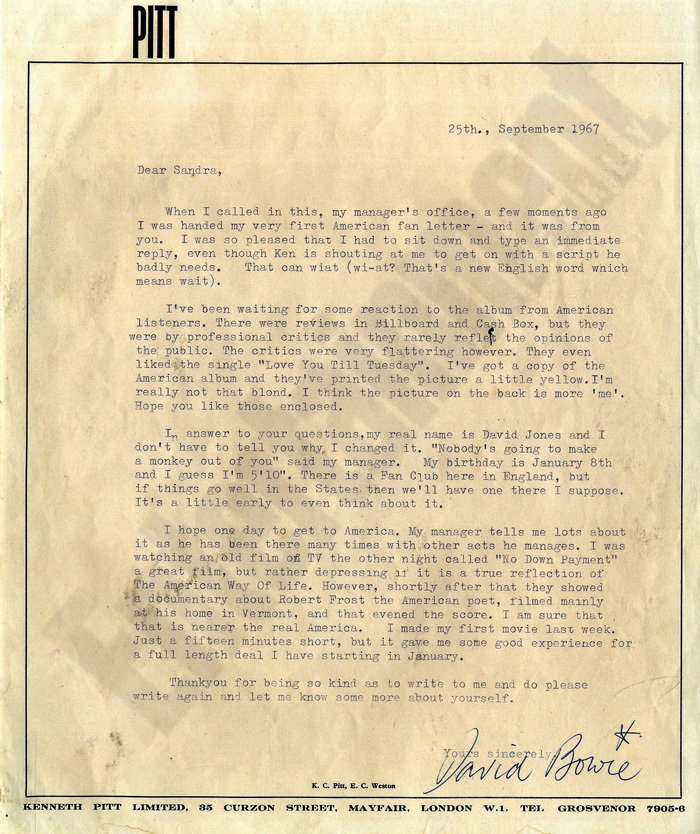

David Bowie’s relationship with America has typified the outsider’s view: an ambivalence ranging from fascination to fear that he expressed in a reply to his first letter from a U.S. fan in 1967 (click to read in large format). The fan, intrepid 14-year-old Sandra Dodd, had gotten her hands on an advance copy of Bowie’s first album and written him to praise his work and offer to start a fan club for him stateside. Bowie’s response is very interesting. We’ve written before about his rise from obscure R&B and folk singer to Ziggy Stardust, which required him to shake off a natural shyness to inhabit his breakout persona. In the letter, the 20-year-old Bowie initially comes off as a naïve, slightly self-involved young pop singer. Then, after answering the usual fan queries—what’s his real name, birthday, height—he turns to the subject of the U.S., a country he had yet to visit. Bowie writes:

I hope one day to get to America. My manager tells me lots about it as he has been there many times with other acts he manages. I was watching an old film on TV the other night called “No Down Payment” a great film, but rather depressing if it is a true reflection of The American Way Of Life. However, shortly after that they showed a documentary about Robert Frost the American poet, filmed mainly at his home in Vermont, and that evened the score. I am sure that that is nearer the real America.

Drawing his impressions from movies, Bowie references two views. The first, Martin Ritt’s 1957 No Down Payment, is full of the banality and melodrama we’ve come to expect from Mad Men, making incisive critiques of mid-50s cultural problems simmering under the surface of the suburbs like alcoholism, racism, and infidelity. As one fan writes, the film depicted what “no one wanted to see… a soiled American Dream,” or what Bowie capitalizes as “The American Way Of Life.”

The other view Bowie takes of the States comes from a film on Robert Frost—most likely 1963’s Robert Frost: A Lover’s Quarrel With the World. Little wonder this film “evened the score” for the lyrical young songwriter, who chooses in his letter to believe it represents the “real America,” a sentiment he would not hold for long.

Flash forward to 1984, and Bowie is an international pop star. Most fans would argue his best work was far behind him, but the 80s saw him break out into more mainstream film roles in The Elephant Man and Labyrinth that kept him at the forefront of American pop culture. His soundtrack work was memorable as well, although the track below “This is Not America,” written with Pat Metheny for The Falcon and the Snowman doesn’t get much attention these days. Bowie’s impressionistic lyrics–which Metheny called “profound and meaningful”–show him in mourning for the country that puzzled his younger self:

A little piece of you

The little peace in me

Will die

For this is not America

Blossom fails to bloom

This season

Promise not to stare

Too long

For this is not a miracle

And again, move forward to 1997, thirty years after Bowie’s letter above, and we find him in a jaundiced mood in “I’m Afraid of Americans” from his album Earthling (the song originally appeared on what may be one of the most cynical films ever made, Showgirls). Bowie explained the genesis of the song in a press release:

I’m Afraid of Americans’ was written by myself and Eno. It’s not as truly hostile about Americans as say “Born in the USA”: it’s merely sardonic. I was traveling in Java when the first McDonalds went up: it was like, “for fuck’s sake.” The invasion by any homogenized culture is so depressing, the erection of another Disney World in, say, Umbria, Italy, more so. It strangles the indigenous culture and narrows expression of life.

The cultural homogenization that so depressed the young Bowie in No Down Payment is now a global phenomenon, and the well-traveled, worldly Bowie seems to harbor few illusions when he sings:

Johnny’s in America

No tricks at the wheel

No one needs anyone

They don’t even just pretend

In the award-winning video, Trent Reznor plays a Travis Bickle-like figure, a menacing creature of alienation and unprovoked, random violence and Bowie a paranoid outsider running from what he perceives as citizens attacking each other on every streetcorner. Stripped of the 50s veneer, it’s a country where people “don’t even pretend”; the violence and misanthropy are now on full display. It’s a view of America that hasn’t dimmed since the mid-nineties. It’s simply moved out of the city and spilled out into the once self-contained suburbs. These three artifacts show Bowie’s evolution in relation to a country that he hoped to find the best in, that nearly always embraced him, and that came to freak him out and piss him off in later years.

via Letters of Note

Josh Jones is a writer and scholar currently completing a dissertation on landscape, literature, and labor.

.

. More than 500 landmarks from the Sefarad—the Sephardic Jews before they were expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492—are fully annotated with current photos, text and special details. Visit Ribadavia, a once-prosperous city in Spain’s northwest mountains, and learn about Jewish wedding traditions from the Middle Ages. The Jewish Quarter of Léon is called the Barrio Húmedo (Wet District) and is known today for its fine wine and food. Use the timeline to keep yourself oriented in chronological history and click Street View to see this vibrant district as it is today.

More than 500 landmarks from the Sefarad—the Sephardic Jews before they were expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492—are fully annotated with current photos, text and special details. Visit Ribadavia, a once-prosperous city in Spain’s northwest mountains, and learn about Jewish wedding traditions from the Middle Ages. The Jewish Quarter of Léon is called the Barrio Húmedo (Wet District) and is known today for its fine wine and food. Use the timeline to keep yourself oriented in chronological history and click Street View to see this vibrant district as it is today.